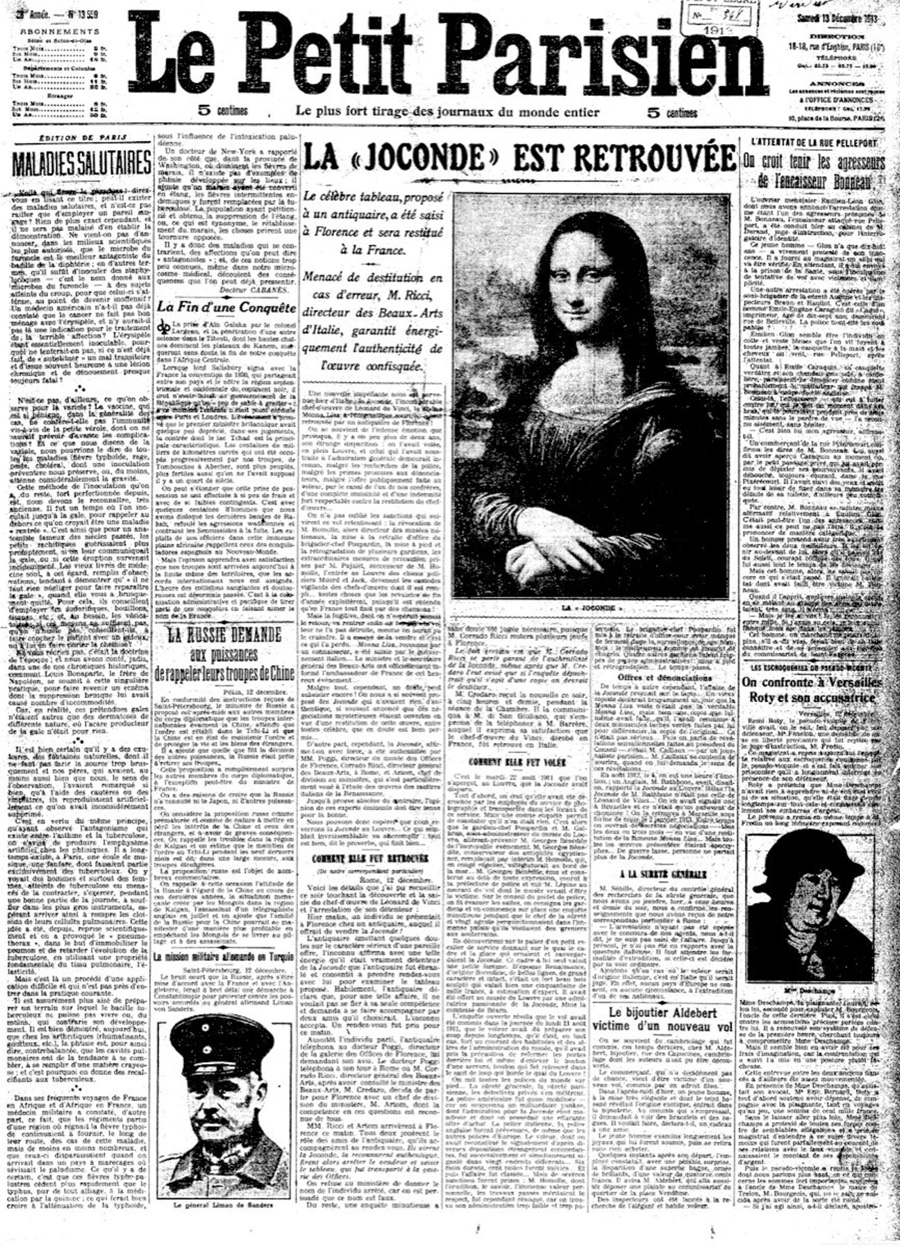

Image by Mark Ordonez, via Flickr Commons

We all have respect, even awe, for the name Stradivarius, even those of us who have never held a violin, let alone played one. The violins — as well as violas, cellos, and other string instruments, including guitars — made by members of the Stradivari family 300 years ago have become symbols of pure sonic quality, still not quite replicable with even 21st-century technology, with rarity and prices to match. But to truly understand the preciousness of the Stradivarius, look not to the auction house but to the northern Italian city of Cremona, home of the Museo del Violino and its collection of some of the best-preserved examples of the 650 surviving Stradivarius instruments in the world.

“Cremona is home to the workshops of some of the world’s finest instrument makers, including Antonio Stradivari, who in the 17th and 18th centuries produced some of the finest violins and cellos ever made,” writes The New York Times’ Max Paradiso.

“The city is getting behind an ambitious project to digitally record the sounds of the Stradivarius instruments for posterity, as well as others by Amati and Guarneri del Gesù, two other famous Cremona craftsmen. And that means being quiet.” It’s all to help the ambitious recording project now creating the Stradivarius Sound Bank, “a database storing all the possible tones that four instruments selected from the Museo del Violino’s collection can produce.”

This requires great efforts on the part of the engineers and the performers, the latter of whom have to play hundreds of scales and arpeggios (examples of which you can hear embedded in The New York Times article) on these staggeringly valuable instruments. But the people of Cremona have to cooperate, too: in the area around the Museo del Violino’s auditorium where the Stradivarius Sound Bank is recording, “the sound of a car engine, or a woman walking in high heels, produces vibrations that run underground and reverberate in the microphones, making the recording worthless.” And so Cremona’s mayor, also the president of the Stradivarius Foundation, “allowed the streets around the museum to be closed for five weeks, and appealed to people in the city to keep it down.”

Few of us alive today have heard the sound of a Stradivarius in person, but that number will shrink further still in future generations. It’s to do with the very nature of these centuries-old instruments which, no matter what kind of efforts go toward making them playable, still seem to have a finite lifespan. “We preserve and restore them,” Paradiso quotes Museo del Violino curator Fausto Cacciatori as saying, “but after they reach a certain age, they become too fragile to be played and they ‘go to sleep,’ so to speak.” The day will presumably come when the last Stradivarius goes to sleep, but by that time the sounds they made will still be wide awake in their digitized second life. And we can be certain, at least, that future generations will think of a musical use for them that we can no more imagine now than Antonio Stradivari could have in his day.

Related Content:

Why Stradivarius Violins Are Worth Millions

Why Violins Have F‑Holes: The Science & History of a Remarkable Renaissance Design

Musician Plays the Last Stradivarius Guitar in the World, the “Sabionari” Made in 1679

Musician Plays the Last Stradivarius Guitar in the World, the “Sabionari” Made in 1679

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.