Be not inhospitable to strangers, lest they be angels in disguise.

More than a few visitors to Paris’ fabled Shakespeare & Company bookshop assume that the quote they see painted over an archway is attributable to Yeats or Shakespeare.

In fact, its author was George Whitman, the store’s late owner, a grand “hobo adventurer” in his 20s who made such an impression that he spent the rest of his life welcoming travelers and encouraging young writers, who flocked to the shop. A great many became Tumbleweeds, the nickname given to those who traded a few hours of volunteer work and a pledge to read a book a day in return for spartan accommodation in the store itself.

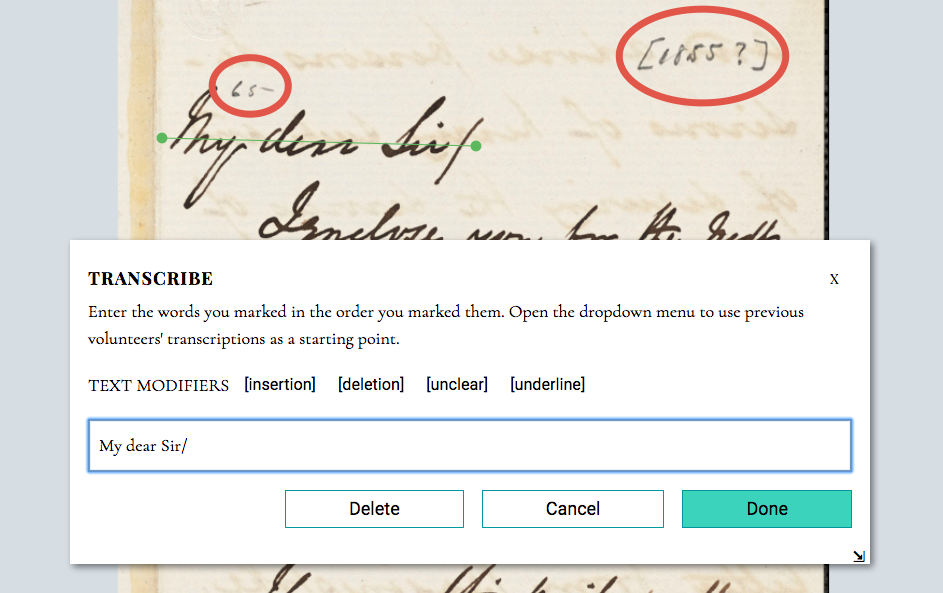

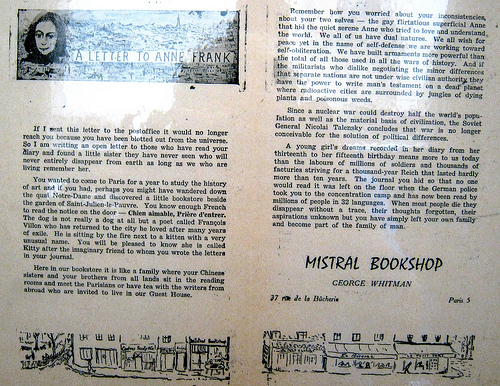

In light of this generosity, Whitman’s 1960 letter to Anne Frank (1929–1945) is all the more moving.

One wonders what inspired him to write it. It’s a not an uncommon impulse, but usually the authors are students close to the same age as Anne was at the time of her death.

Perhaps it was an interaction with a Tumbleweed.

Had she survived the horrors of the Nazi concentration camps that exterminated all but one inhabitant of the Secret Annex in which she penned her famous diary, she would have made a great one.

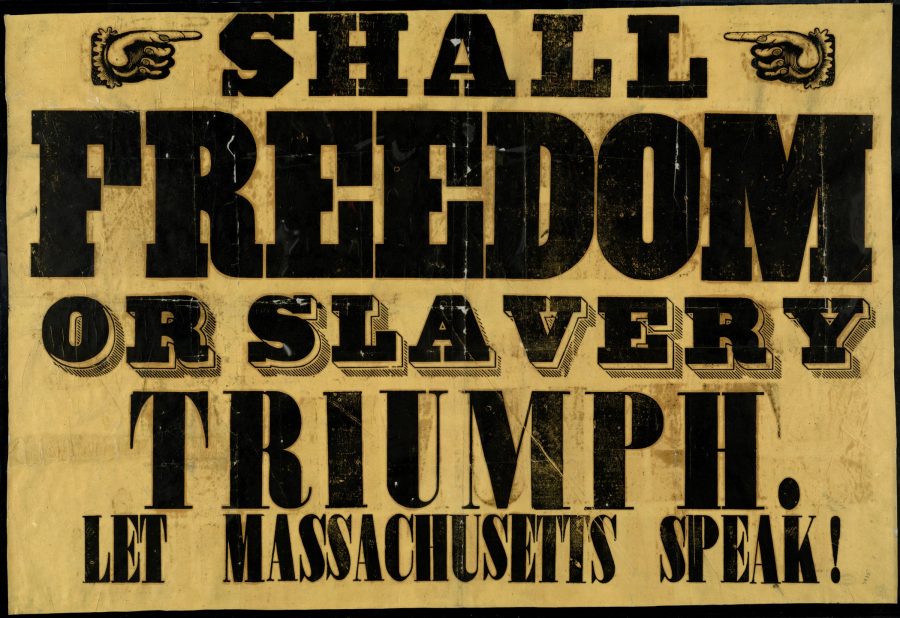

He refrained from mentioning his own service in World War II, possibly because he was posted to a remote weather station in Greenland. Unlike other American veterans, he hadn’t witnessed with his own eyes the sort of hell she endured. If he had, he might not have been able to address her with such initial lightness of tone.

One can’t help but think how delighted the rambunctious young teen would have been by his sense of humor, his descriptions of his bohemian booklovers’ paradise—then called Le Mistral—and references to his dog, François Villon, and cat, Kitty, named in honor of Anne’s pet name for her diary.

His profound observations on the impermanence of life and the politics of war continue to resonate deeply with those who read the letter as its intended recipients’ proxies:

Le Mistral

37 rue de la Bûcherie

Dear Anne Frank,

If I sent this letter to the post office it would no longer reach you because you have been blotted out from the universe. So I am writing an open letter to those who have read your diary and found a little sister they have never seen who will never entirely disappear from earth as long as we who are living remember her.

You wanted to come to Paris for a year to study the history of art and if you had, perhaps you might have wandered down the quai Notre-Dame and discovered a little bookstore beside the garden of Saint-Julien-le-Pauvre. You know enough French to read the notice on the door—Chien aimable, Priere d’entrer. The dog is not really a dog at all but a poet called Francois Villon who has returned to the city he loved after many years of exile. He is sitting by the fire next to a kitten with a very unusual name. You will be pleased to know she is called Kitty after the imaginary friend to whom you wrote the letters in your journal.

Here in our bookstore it is like a family where your Chinese sisters and your brothers from all lands sit in the reading rooms and meet the Parisians or have tea with the writers from abroad who are invited to live in our Guest House.

Remember how you worried about your inconsistencies, about your two selves—the gay flirtatious superficial Anne that hid the quiet serene Anne who tried to love and understand the world. We all of us have dual natures. We all wish for peace, yet in the name of self-defense we are working toward self-obliteration. We have built armaments more powerful than the total of all those used in all the wars in history. And if the militarists who dislike negotiating the minor differences that separate nations are not under the wise civilian authority they have the power to write man’s testament on a dead planet where radioactive cities are surrounded by jungles of dying plants and poisonous weeds.

Since a nuclear could destroy half the world’s population as well as the material basis of civilization, the Soviet General Nikolai Talensky concludes that war is no longer conceivable for the solution of political differences.

A young girl’s dreams recorded in her diary from her thirteenth to her fifteenth birthday means more to us today than the labors of millions of soldiers and thousands of factories striving for a thousand-year Reich that lasted hardly more than ten years. The journal you hid so that no one would read it was left on the floor when the German police took you to the concentration camp and has now been read by millions of people in 32 languages. When most people die they disappear without a trace, their thoughts forgotten, their aspirations unknown, but you have simply left your own family and become part of the family of man.

George Whitman

via Letters of Note

Related Content:

Watch the Only Known Footage of Anne Frank

Anne Frank’s Diary: From Reject Pile to Bestseller

8‑Year-Old Anne Frank Plays in a Sandbox on a Summer Day, 1937

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Join her in New York City this Thursday for Necromancers of the Public Domain, in which a long neglected book is reframed as a low budget variety show. Follow her @AyunHalliday.