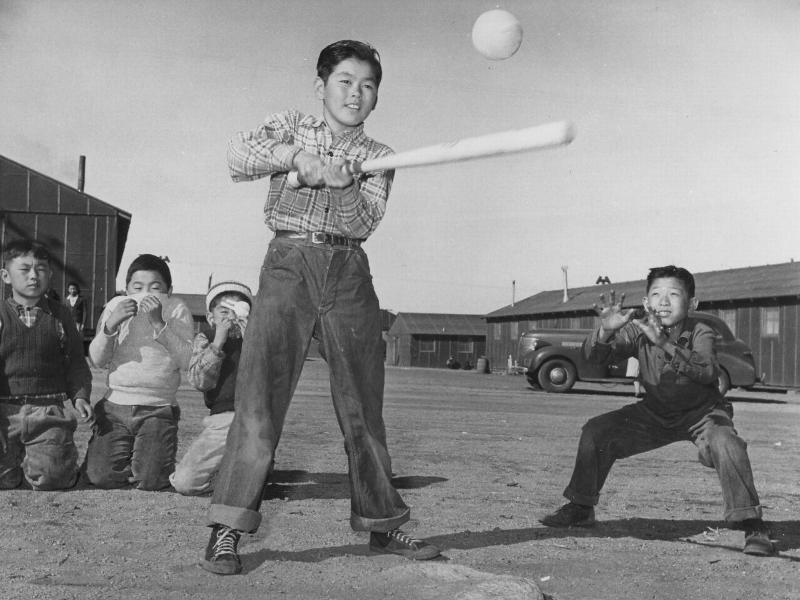

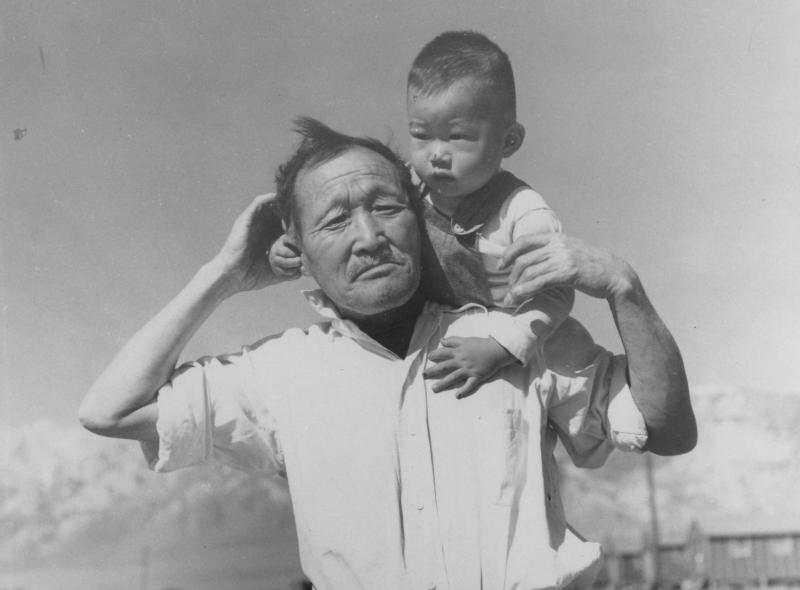

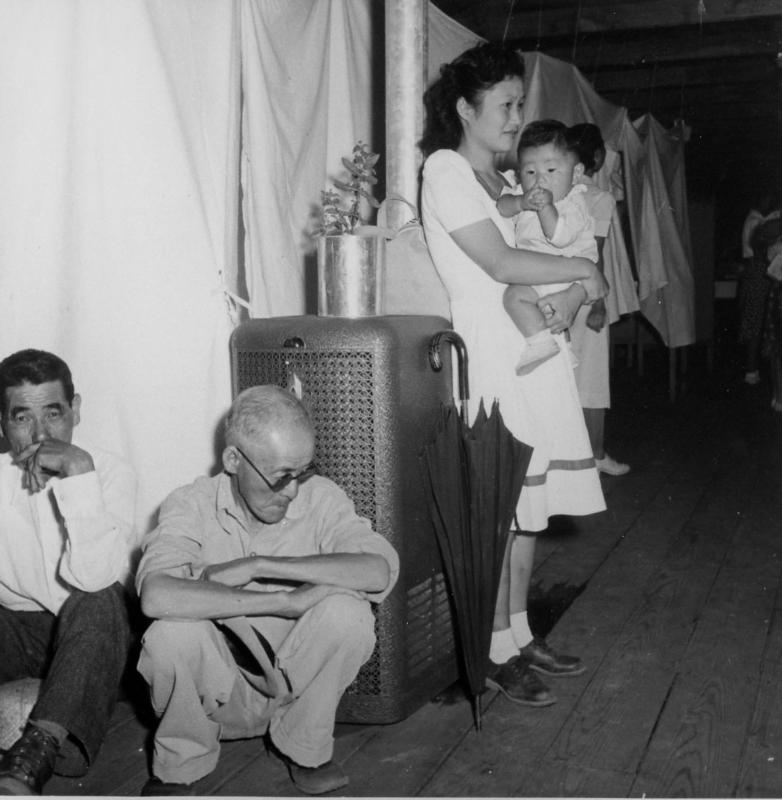

It’s difficult to appraise the complicated legacy of Franklin D. Roosevelt. His New Deal policies are credited for lifting millions out of destitution, and they created opportunities for struggling artists and writers, many of whom went on to become some of the country’s most celebrated. But Roosevelt also compromised with racist southern senators like Mississippi’s Theodore Bilbo, and underwrote housing segregation, job and pay discrimination, and exclusions in his economic recovery aimed most squarely at African-Americans. He is lauded as a wartime leader in the fight against Nazism. But he built concentration camps on U.S. soil when he interned over 100,000 Japanese Americans after Pearl Harbor. His commitment to isolationism before the war and his “moral failure—or indifference” to the plight of European Jews, thousands of whom were denied entry to the U.S., has come under justifiable scrutiny from historians.

Both blame and praise are well warranted, and not his alone to bear. Yet, for all his serious lapses and wartime crimes, FDR consistently had an astute and idealistic economic vision for the country. In his 1944 State of the Union address, he denounced war profiteers and “selfish and partisan interests,” saying, “if ever there was a time to subordinate individual or group selfishness to the national good, that time is now.”

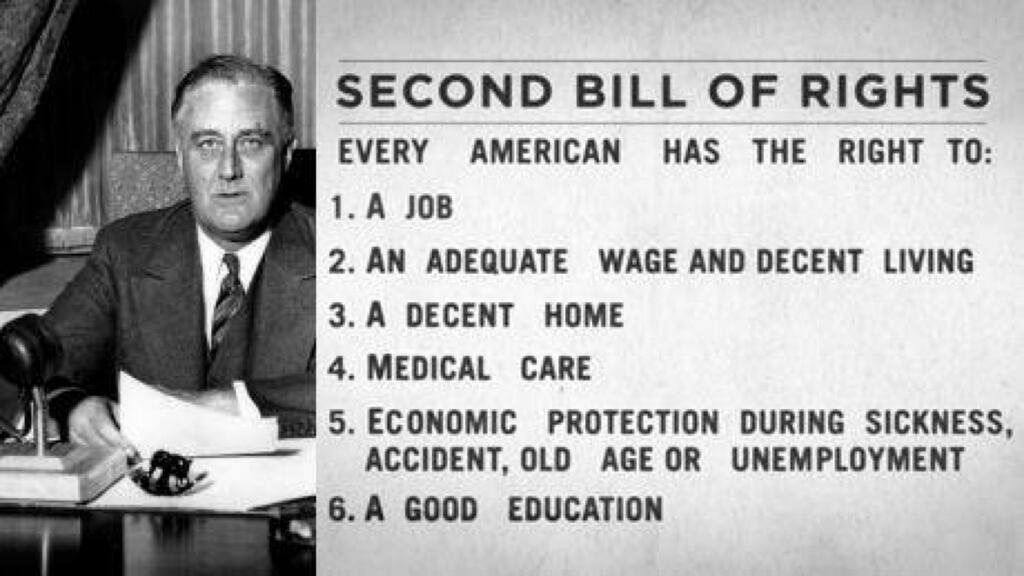

He went on to enumerate a series of proposals “to maintain a fair and stable economy at home” while the war still raged abroad. These include taxing “all unreasonable profits, both individual and corporate” and enacting regulations on food prices. The speech is most extraordinary, however, for the turn it takes at the end, when the president proposes and clearly articulates a “second Bill of Rights,” arguing that the first one had “proved inadequate to assure us equality in the pursuit of happiness.”

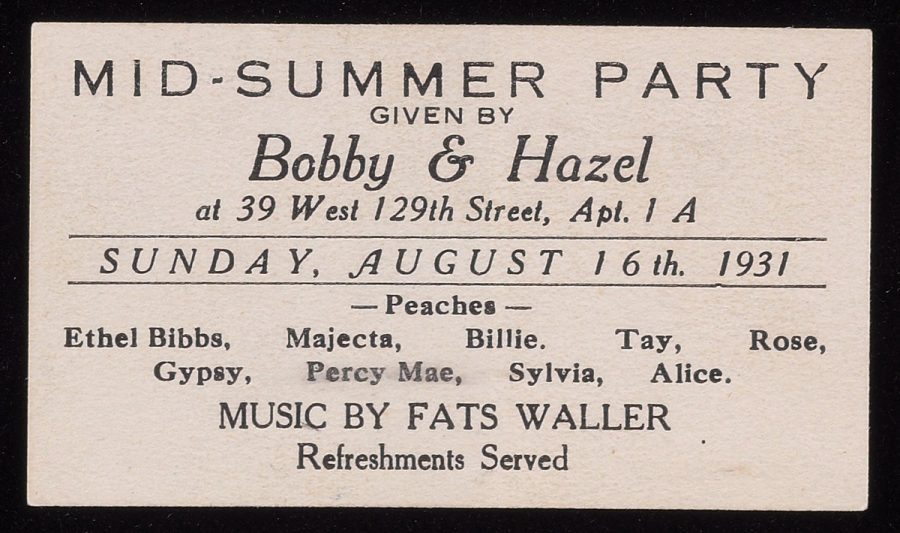

Roosevelt did not take the value of equality for granted or merely invoke it as a slogan. Though its role in his early policies was sorely lacking, he showed in 1941 that he could be moved on civil rights issues when, in response to a march on Washington planned by Bayard Rustin, A. Philip Randolph, and other activists, he desegregated federal hiring and the military. In his 1944 speech, Roosevelt strongly suggests that economic inequality is a precursor to Fascism, and he offers a progressive political theory as a hedge against Soviet Communism.

“We have come to a clear realization,” he says, “of the fact that true individual freedom cannot exist without economic security. ‘Necessitous men are not free men.’ People who are hungry and out of a job are the stuff of which dictatorships are made. In our day these economic truths have become accepted as self-evident.” In the footage at the top of the post, you can see Roosevelt himself read his new Bill of Rights. Read the transcript yourself just below:

We have accepted, so to speak, a second Bill of Rights under which a new basis of security and prosperity can be established for all regardless of station, race, or creed.

Among these are:

The right to a useful and remunerative job in the industries or shops or farms or mines of the Nation;

The right to earn enough to provide adequate food and clothing and recreation;

The right of every farmer to raise and sell his products at a return which will give him and his family a decent living;

The right of every businessman, large and small, to trade in an atmosphere of freedom from unfair competition and domination by monopolies at home or abroad;

The right of every family to a decent home;

The right to adequate medical care and the opportunity to achieve and enjoy good health;

The right to adequate protection from the economic fears of old age, sickness, accident, and unemployment;

The right to a good education.

All of these rights spell security. And after this war is won we must be prepared to move forward, in the implementation of these rights, to new goals of human happiness and well-being.

Roosevelt died in office before the war ended. His successor tried to carry forward his economic and civil rights initiatives with the “Fair Deal,” but congress blocked nearly all of Truman’s proposed legislation. We might imagine an alternate history in which Roosevelt lived and found a way through force of will to enact his “second Bill of Rights,” honoring his promise to every “station, race” and “creed.” Yet in any case, his fourth term was nearly at an end, and he would hardly have been elected to a fifth.

But FDR’s progressive vision has endured. Many seeking to chart a course for the country that tacks away from political extremism and toward economic justice draw directly from Roosevelt’s vision of freedom and security. His new bill of rights is striking for its political boldness. Its proposals may have had their clearest articulation three years earlier in the famous “Four Freedoms” speech. In it he says, “the basic things expected by our people of their political and economic systems are simple. They are:

Equality of opportunity for youth and for others.

Jobs for those who can work.

Security for those who need it.

The ending of special privilege for the few.

The preservation of civil liberties for all.

The enjoyment of the fruits of scientific progress in a wider and constantly rising standard of living.

These are the simple, the basic things that must never be lost sight of in the turmoil and unbelievable complexity of our modern world. The inner and abiding strength of our economic and political systems is dependent upon the degree to which they fulfill these expectations.

Guaranteeing jobs, if not income, for all and a “constantly rising standard of living” may be impossible in the face of automation and environmental degradation. Yet, most of Roosevelt’s principles may not only be realizable, but perhaps, as he argued, essential to preventing the rise of oppressive, authoritarian states.

Related Content:

Franklin D. Roosevelt Says to Moneyed Interests (EG Bankers) in 1936: “I Welcome Their Hatred!”

Rare Footage: Home Movie of FDR’s 1941 Inauguration

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness