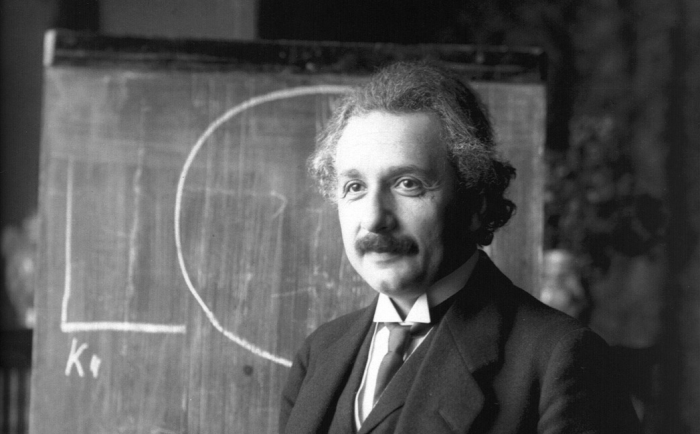

Image by Ferdinand Schmutzer, via Wikimedia Commons

“Should we allow celebrities to discuss politics?” goes one variation on an evergreen headline and supposedly legitimate public debate. No amount of public disapproval could have stopped some of the most outspoken public figures, and we’d be the worse off for it in many cases. Muhammad Ali, John Lennon, Nina Simone, George Carlin, Roger Waters, Margaret Cho, and, yes, Meryl Streep—millions of people have been very grateful (and many not) for these artists’ political commentary. When it comes to scientists, however, we tend to see more baseless accusations of political speech than overwhelming evidence of it.

But there have been those few scientists and philosophers who were also celebrities, and who made their political views well-known without reservation. Bertrand Russell was such a person, as was Albert Einstein, who took up the causes of world peace and of racial justice in the post-war years. As we’ve previously noted, Einstein’s commitments were both philanthropic and activist, and he formed close friendships with Paul Robeson, W.E.B. Du Bois, Marian Anderson, and other prominent black leaders.

Einstein also co-chaired an anti-lynching campaign and issued a scathing condemnation of racism during a speech he gave in 1946 at the alma mater of Langston Hughes and Thurgood Marshall in which he called racism “a disease of white people.” That same year, notes On Being’s executive editor Trent Gilliss, Einstein “penned one of his most articulate and eloquent essays advocating for the civil rights of black people in America.” Titled “The Negro Question” and published in the January 1946 edition of Pageant magazine, the essay, writes Gilliss, “was intended to address a primarily white readership.”

Einstein begins by answering the inevitable objection, “What right has he to speak about things which concern us alone, and which no newcomer should touch?” To this, the famed physicist answers, “I do not think such a standpoint is justified.” Einstein believed he had a unique perspective: “One who has grown up in an environment takes much for granted. On the other hand, one who has come to this country as a mature person may have a keen eye for everything peculiar and characteristic.” Speaking freely about his observations, Einstein felt “he may perhaps prove himself useful.”

Then, after praising the country’s “democratic trait” and its citizens’ “healthy self-confidence and natural respect for the dignity of one’s fellow-man,” he plainly observes that this “sense of equality and human dignity is mainly limited to men of white skins.” Anticipating a casually racist defense of “natural” differences, Einstein replies:

I am firmly convinced that whoever believes this suffers from a fatal misconception. Your ancestors dragged these black people from their homes by force; and in the white man’s quest for wealth and an easy life they have been ruthlessly suppressed and exploited, degraded into slavery. The modern prejudice against Negroes is the result of the desire to maintain this unworthy condition.

The ancient Greeks also had slaves. They were not Negroes but white men who had been taken captive in war. There could be no talk of racial differences. And yet Aristotle, one of the great Greek philosophers, declared slaves inferior beings who were justly subdued and deprived of their liberty. It is clear that he was enmeshed in a traditional prejudice from which, despite his extraordinary intellect, he could not free himself.

Like the ancient Greeks, Americans’ prejudices are “conditioned by opinions and emotions which we unconsciously absorb as children from our environment.” And racist attitudes are both causes and effects of economic exploitation, learned behaviors that emerge from historical circumstances, yet we “rarely reflect” how powerful the influence of tradition is “upon our conduct and convictions.” The situation can be remedied, Einstein believed, though not “quickly healed.” The “man of good will,” he wrote, “must have the courage to set an example by word and deed, and must watch lest his children become influenced by this racial bias.”

Read the full essay at On Being, and learn more about Einstein’s committed anti-racist activism from Fred Jerome and Rodger Taylor’s 2006 book Einstein on Race and Racism.

Related Content:

Listen as Albert Einstein Calls for Peace and Social Justice in 1945

Albert Einstein Expresses His Admiration for Mahatma Gandhi, in Letter and Audio

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness