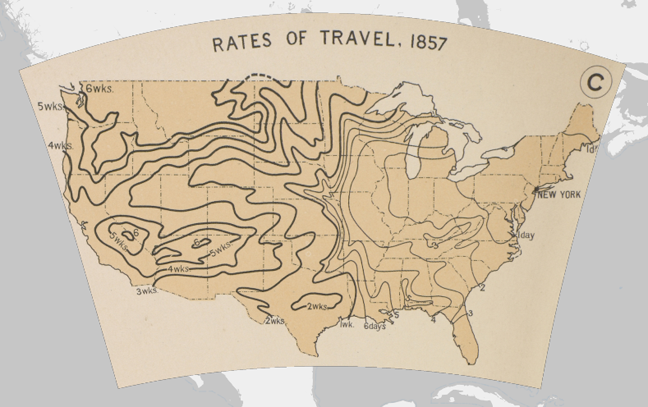

In 1902, the newly established Carnegie Institution of Washington set out to develop “a really first rate atlas of American history.” Work on the atlas began in earnest in 1912, under the direction of the naval historian Charles O. Paullin, who spent the better part of the next 15 years bringing it to life. In 1929, the American Geographic Society (AGS), along with the eminent geographer John K. Wright, took over the project and brought it to completion. The Atlas of the Historical Geography of the United States was finally published in 1932 to wide critical acclaim. Called a “monument to historical scholarship,” the compendium featured nearly 700 individual maps that gave visual insights into 500 years of American history. Topic covered included the “exploration and settlement of the North American continent, the location of colleges and churches, disputes over international and state boundaries, voting in presidential elections and in Congress, reforms from women’s suffrage to workmen’s compensation, transportation, industries, agriculture, commerce, the distribution of wealth, military history” and much more.

The Atlas of the Historical Geography of the United States remains a valuable historical resource today. But, for all of these years, it had one notable shortcoming. Around the time of its first publication, John K. Wright acknowledged that “The ideal historical atlas might well be a collection of motion-picture maps, if these could be displayed on the pages of a book without the paraphernalia of projector, reel, and screen.” The technology that would lend itself to creating motion-picture maps wasn’t available in the 1930s. But it is today. And thanks to the University of Richmond’s Digital Scholarship Lab, we can now view The Atlas of the Historical Geography of the United States in a new digital, sometimes animated format. If you want to see a good example of historical data put into motion, then you might want to check out this map of American Explorations in the West, 1803–1852. (Click here and then click “Animate” at the bottom of the screen.) This map will trace for you the expeditions of Lewis and Clark and many other explorers. Then, if you’re ready to be an explorer yourself, you can start your journey through the digitized atlas by entering the Table of Contents.

Related Content:

Visualizing Slavery: The Map Abraham Lincoln Spent Hours Studying During the Civil War

Henry David Thoreau’s Hand-Drawn Map of Cape Cod (1866)

An Interactive Map of Odysseus’ 10-Year Journey in Homer’s Odyssey

Geography of World Cultures by Martin Lewis (Stanford) in our collection of 825 Free Online Courses