In 1951, Carl Djerassi, a chemist working in an obscure lab in Mexico City, created the first progesterone pill. Little did he know that, a decade later, 1.2 million women would be “on the Pill” in America, exercising unprecedented control over their reproductive rights. By 1967, that number would reach 12.5 million women worldwide.

It was fortuitous timing, seeing that the post-war global population was starting to surge. It took 125 years (1800–1925) for the global population to move from one billion to two billion (see historical chart), but only 35 years (1925–1960) for that number to reach three billion. Non-profits like the Population Council were founded to think through emerging population questions, and by the mid-1960s, they began publishing a peer-reviewed journal called Studies in Family Planning and also working with Walt Disney to produce a 10-minute educational cartoon. You can watch Family Planning above.

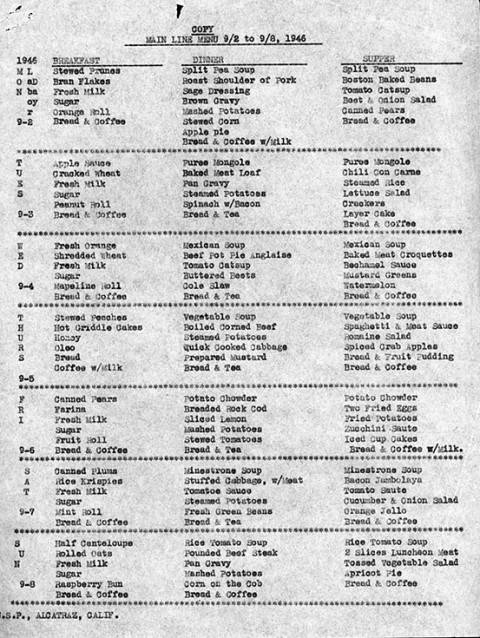

Eventually translated into 25 languages, the film avoids anything sexually explicit. The family planning advice is vague at best and, perversely but not surprisingly, only male characters get a real voice in the production. But lest you think that Disney was breaking any real ground here, let me remind you of its more daring foray into sex-ed films two decades prior. That’s when it produced The Story of Menstruation (1946), a more substantive film shown to 105 million students across the US.

You can find Family Planning and The Story of Menstruation housed in the Animation section of our collection, 4,000+ Free Movies Online: Great Classics, Indies, Noir, Westerns, Documentaries & More.

Related Content:

No Women Need Apply: A Disheartening 1938 Rejection Letter from Disney Animation

How Walt Disney Cartoons Are Made

Donald Duck Wants You to Pay Your Taxes (1943)

Walt Disney Presents the Super Cartoon Camera (1957)