Here’s a fascinating glimpse of the very first Bloomsday celebration, filmed in Dublin in 1954.

The footage shows the great Irish comedic writer Brian O’Nolan, better known by his pen name Flann O’Brien, appearing very drunk as he sets off with two other renowned post-war Irish writers, Patrick Kavanagh and Anthony Cronin, and a cousin of James Joyce, a dentist named Tom Joyce, on a pilgrimage to visit the sites in James Joyce’s epic novel Ulysses.

The footage was taken by John Ryan, an artist, publisher and pub owner who organized the event. The idea was to retrace the steps of Leopold Bloom and other characters from the novel, but as Peter Costello and Peter van de Kamp explain in this humerous passage from their book, Flann O’Brien: An Illustrated Biography, things began to go awry right from the start:

The date was 16 June, 1954, and though it was only mid-morning, Brian O’Nolan was already drunk.

This day was the fiftieth anniversary of Mr. Leopold Bloom’s wanderings through Dublin, which James Joyce had immortalised in Ulysses.

To mark this occasion a small group of Dublin literati had gathered at the Sandycove home of Michael Scott, a well-known architect, just below the Martello tower in which the opening scene of Joyce’s novel is set. They planned to travel round the city through the day, visiting in turn the scenes of the novel, ending at night in what had once been the brothel quarter of the city, the area which Joyce had called Nighttown.

Sadly, no-one expected O’Nolan to be sober. By reputation, if not by sight, everyone in Dublin knew Brian O’Nolan, otherwise Myles na Gopaleen, the writer of the Cruiskeen Lawn column in the Irish Times. A few knew that under the name of Flann O’Brien, he had written in his youth a now nearly forgotten novel, At Swim-Two-Birds. Seeing him about the city, many must have wondered how a man with such extreme drinking habits, even for the city of Dublin, could have sustained a career as a writer.

As was his custom, he had been drinking that morning in the pubs around the Cattle Market, where customers, supposedly about their lawful business, would be served from 7:30 in the morning. Now retired from the Civil Service, on grounds of “ill-health”, he was earning his living as a free-lance journalist, writing not only for the Irish Times, but for other papers and magazines under several pen-names. He needed to write for money as his pension was a tiny one. But this left little time for more creative work. In fact, O’Nolan no longer felt the urge to write other novels.

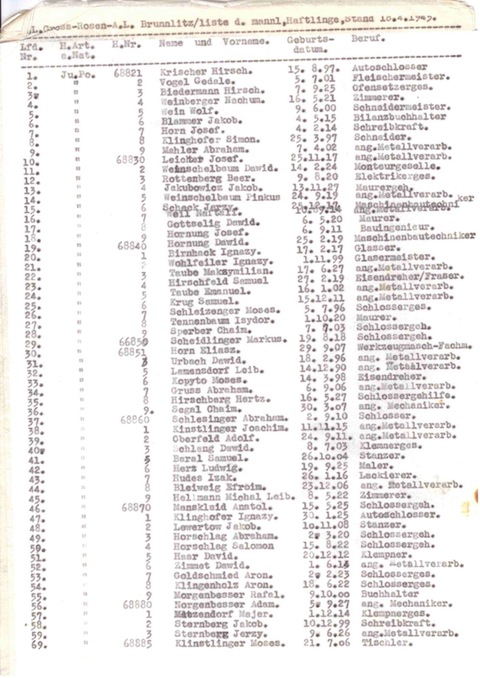

The rest of the party, that first Bloomsday, was made up of the poet Patrick Kavanagh, the young critic Anthony Cronin, a dentist named Tom Joyce, who as Joyce’s cousin represented the family interest, and John Ryan, the painter and businessman who owned and edited the literary magazine Envoy. The idea of the Bloomsday celebration had been Ryan’s, growing naturally out of a special Joyce issue of his magazine, for which O’Nolan had been guest editor.

Ryan had engaged two horse drawn cabs, of the old fashioned kind, which in Ulysses Mr. Bloom and his friends drive to poor Paddy Dignam’s funeral. The party were assigned roles from the novel. Cronin stood in for Stephen Dedalus, O’Nolan for his father, Simon Dedalus, John Ryan for the journalist Martin Cunningham, and A.J. Leventhal, the Registrar of Trinity College, being Jewish, was recruited to fill (unkown to himself according to John Ryan) the role of Leopold Bloom.

Kavanagh and O’Nolan began the day by deciding they must climb up to the Martello tower itself, which stood on a granite shoulder behind the house. As Cronin recalls, Kavanagh hoisted himself up the steep slope above O’Nolan, who snarled in anger and laid hold of his ankle. Kavanagh roared, and lashed out with his foot. Fearful that O’Nolan would be kicked in the face by the poet’s enormous farmer’s boot, the others hastened to rescue and restrain the rivals.

With some difficulty O’Nolan was stuffed into one of the cabs by Cronin and the others. Then they were off, along the seafront of Dublin Bay, and into the city.

In pubs along the way an enormous amount of alcohol was consumed, so much so that on Sandymount Strand they had to relieve themselves as Stephen Dedalus does in Ulysses. Tom Joyce and Cronin sang the sentimental songs of Tom Moore which Joyce had loved, such as Silent, O Moyle. They stopped in Irishtown to listen to the running of the Ascot Gold Cup on a radio in a betting shop, but eventually they arrived in Duke Street in the city centre, and the Bailey, which John Ryan then ran as a literary pub.

They went no further. Once there, another drink seemed more attractive than a long tour of Joycean slums, and the siren call of the long vanished pleasures of Nighttown.

Celebrants of the first Bloomsday pause for a photo in Sandymount, Dublin on the morning of June 16, 1954. From left are John Ryan, Anthony Cronin, Brian O’Nolan (a.k.a. Flann O’Brien), Patrick Kavanagh and Tom Joyce, cousin of James Joyce.

via Biblioklept/Antoine Malette

Related content:

On Bloomsday, Hear James Joyce Read From his Epic Ulysses, 1924

Stephen Fry Explains His Love for James Joyce’s Ulysses

Henri Matisse Illustrates 1935 Edition of James Joyce’s Ulysses