Images via Wikimedia Commons

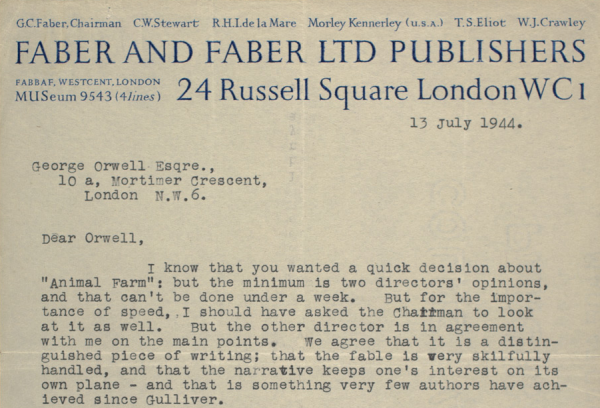

I first heard the phrase “terminal aesthetic” in a class on T.S. Eliot and Ezra Pound, who collaborated on the final version of Eliot’s post World War I edifice, The Waste Land. That poem, went the argument, traveled so far out on the edge, with its fragmented language and incongruous literary and historical references, that it couldn’t possibly serve as a basis for new forms of writing. Instead, Eliot had walked to the end of a promontory, and planted a flag to mark a creative and, perhaps, spiritual dead end.

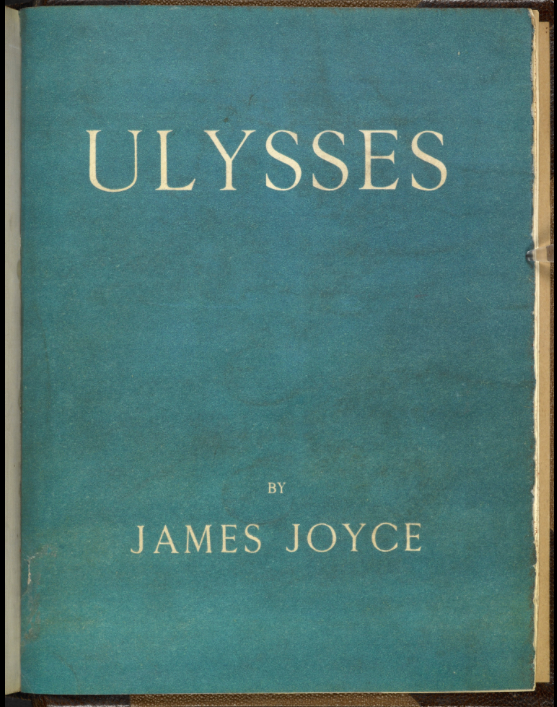

I’m not sure I agree, but the idea has always fascinated me, that a work of art could be so rarified, so ahead of its readers, so idiosyncratic, inaccessible, and strange, that it might escape all attempts at imitation and domestication. There may be no greater example of such a project than James Joyce’s final work, Finnegans Wake. For all the admiration and obsession it has inspired, for the many artists who have learned from this strange book (including, notably, A Clockwork Orange’s Anthony Burgess), it remains for nearly all of us, in the words of H.G. Wells, a repository of “vast riddles.”

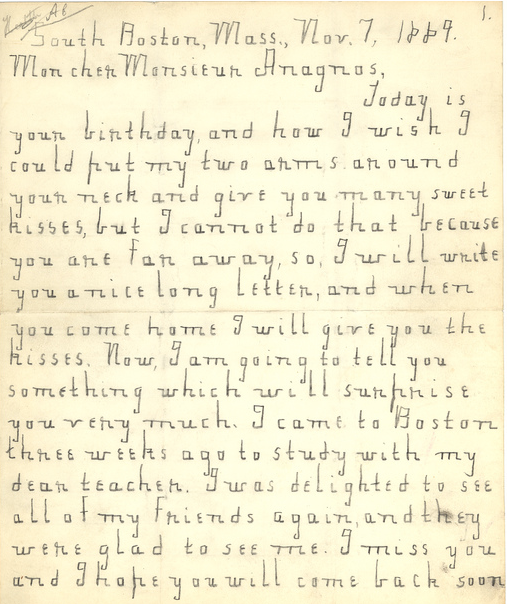

Wells wrote to Joyce in 1928, regarding what was then simply known as the Irish author’s “Work in Progress.” Excerpts were just then appearing piecemeal in journals and being “passed around in literary circles,” writes Letters of Note,” to a largely baffled audience.” It seems that Wells had been asked—perhaps by Joyce himself—to offer public comment or a blurb of some sort. He declined. “I’ve been studying you and thinking over you a lot,” he begins. “The outcome is that I don’t think I can do anything for the propaganda of your work.”

Wells professes a “great personal liking” for Joyce, but then details the “absolutely different courses” their lives and thought had taken: “Your mental existence is obsessed by a monstrous system of contradictions,” Wells writes, and elaborates with some distaste on Joyce’s scatological and theological obsessions. Then he turns to the work at hand, which would become Finnegans Wake:

Now with regard to this literary experiment of yours. It’s a considerable thing because you are a very considerable man and you have in your crowded composition a mighty genius for expression which has escaped discipline. But I don’t think it gets anywhere. You have turned your back on common men — on their elementary needs and their restricted time and intelligence… What is the result? Vast riddles. Your last two works have been more amusing and exciting to write than they will ever be to read. Take me as a typical common reader. Do I get much pleasure from this work? … No. So I ask: Who the hell is this Joyce who demands so many waking hours of the few thousand I have still to live for a proper appreciation of his quirks and fancies and flashes of rendering?

A fair enough question, I suppose, and fair enough critique—one we might expect from the self-described “scientific, constructive” mind of Wells. “To me,” he writes, “it is a dead end.”

Finnegans Wake continues to baffle and frustrate contemporary readers, and writers like Michael Chabon, who once described it as “hulking, chimerical, gibbering to itself in an outlandish tongue, a frightening beast out of legend.” Does Finnegans Wake speak to us common readers, or does it “gibber” only to itself, leaving the rest of us behind? Like Ulysses, it’s best to traverse the book with a guide. Burgess has written a few (and has even audaciously abridged the novel). We must also remember that Finnegans Wake is as much about sound as sense, and should be heard as well as read. (Hear Joyce himself read from the novel here.)

Then there are the “fractal” explications of the novel, like Terrence McKenna’s and that of a recent scientific study of its “multifractality.” I doubt any of this would have moved Wells, who demanded a clarity of thought and expression that was anathema to the later Joyce, immersed as he was in a project to disassemble the roots and branches of language and history and repurpose them for his own means. For all his puzzlement over Joyce’s “experiment,” however, Wells does seem to have found exactly the right word to capture Joyce’s radical literary aims, describing the writer of Ulysses and the inscrutable Finnegans Wake as “insurrectionary.”

Read Wells’ full letter at Letters of Note, who also bring us a letter from a “Vladimir Dixon,” written in imitation of Finnegans Wake, and possibly penned by Joyce himself.

Related Content:

James Joyce Reads ‘Anna Livia Plurabelle’ from Finnegans Wake

Hear All of Finnegans Wake Read Aloud: A 35 Hour Reading

H.G. Wells Pans Fritz Lang’s Metropolis in a 1927 Movie Review: It’s “the Silliest Film”

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness