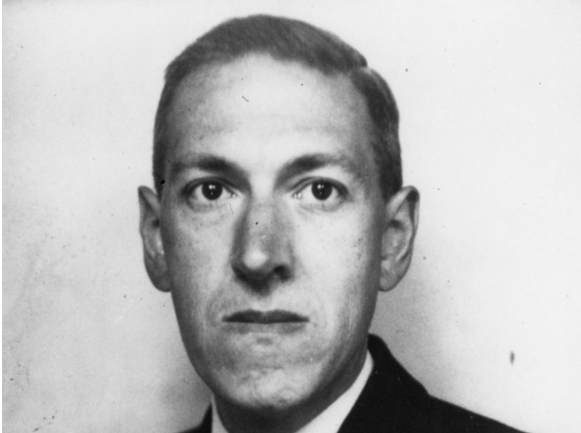

Image by Lucius B. Truesdell, via Wikimedia Commons

H.P. Lovecraft is remembered as a brilliant fantasist, a creator of a completely unique universe of horror. He’s also remembered, unfortunately, as a bigot. But the author whose head—to the chagrin of some—provided the model for the World Fantasy Award is not often remembered as a particularly good writer. Or rather, I should say, a particularly good stylist. His writing can sound stiflingly archaic, overstuffed with Victorianisms. “His prose, “writes Scott Malthouse, “can be turgid and adjectives suffocating,” and “his characters tend to be as thin as the paper they’re printed on.”

Writers love him, Malthouse argues, because he was such an original “world builder,” not because he was a fine artist. Elizabeth Bear at Tor echoes the sentiment, writing that Lovecraft’s work is “criticized for its style, for its purpleness and density and failures of structure,” yet still evokes such a potent response that “the Lovecraftian universe must be considered a collaborative effort at this point,” since so many writers have furthered his “appealingly bleak” vision. You can download a good part of his collected works in ebook and audiobook formats here.

So perhaps he isn’t such a bad writer after all? In any case, he’s certainly a very distinctive one whose style, like Joseph Conrad’s, say, or even William Faulkner’s, endears readers precisely for its feverish excesses. Lovecraft himself was very self-conscious about his craft and took writing very seriously—enough to have published a lengthy, highly detailed essay called “Literary Composition” which tackles in several paragraphs a host of issues the writer must contend with: grammar, “reading,” vocabulary, “elemental phrases,” description, narration, “fictional narration,” “unity, mass, coherence,” and “forms of composition.” We won’t recite the whole of his advice here—you can read the whole thing for yourself. But to give you some of the flavor of Lovecraft’s pedagogy, we bring you his list of twenty “types of mistakes” young writers make.

See his complete list below.

- Erroneous plurals of nouns, as vallies or echos.

- Barbarous compound nouns, as viewpoint or upkeep.

- Want of correspondence in number between noun and verb where the two are widely separated or the construction involved

- Ambiguous use of pronouns.

- Erroneous case of pronouns, as whom for who, and vice versa, or phrases like “between you and I,” or “Let we who are loyal, act promptly.”

- Erroneous use of shall and will, and of other auxiliary verbs.

- Use of intransitive for transitive verbs, as “he was graduated from college,” or vice versa, as “he ingratiated with the tyrant.”

- Use of nouns for verbs, as “he motored to Boston,” or “he voiced a protest,”

- Errors in moods and tenses of verbs, as “If I was he, I should do otherwise”, or “He said the earth was”

- The split infinitive, as “to calmly ”

- The erroneous perfect infinitive, as “Last week I expected to have met”

- False verb-forms, as “I pled with him.”

- Use of like for as, as “I strive to write like Pope wrote.”

- Misuse of prepositions, as “The gift was bestowed to an unworthy object,” or “The gold was divided between the five men.”

- The superfluous conjunction, as “I wish for you to do this.”

- Use of words in wrong senses, as “The book greatly intrigued me”, “Leave me take this”, “He was obsessed with the idea”, or “He is a meticulous”

- Erroneous use of non-Anglicised foreign forms, as “a strange phenomena”, or “two stratas of clouds”.

- Use of false or unauthorised words, as burglarise or supremest.

- Errors of taste, including vulgarisms, pompousness, repetition, vagueness, ambiguousness, colloquialism, bathos, bombast, pleonasm, tautology, harshness, mixed metaphor, and every sort of rhetorical awkwardness.

- Errors of spelling and punctuation, and confusion of forms such as that which leads many to place an apostrophe in the possessive pronoun its.

Most of this is solid, common sense writing advice. Some of it isn’t. As with all things Lovecraft, you would be wise to use your discretion. A full read of Lovecraft’s treatise on composition will give you some sense of how to begin writing your own Lovecraft pastiche. For even more of his advice on the writing of fiction—particularly, as he called it, “weird fiction,” see his list of five tips for horror writing, which we featured in October.

Related Content:

H.P. Lovecraft Gives Five Tips for Writing a Horror Story, or Any Piece of “Weird Fiction”

H.P. Lovecraft’s Classic Horror Stories Free Online: Download Audio Books, eBooks & More

Lovecraft: Fear of the Unknown (Free Documentary)

Stephen King’s Top 20 Rules for Writers

Writing Tips by Henry Miller, Elmore Leonard, Margaret Atwood, Neil Gaiman & George Orwell

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness