Image via New York Public Library

Increasingly Facebook seems a virtual pet cemetery, with images of recently departed cats and dogs buttressed with words of heartbreak and consolation. It feels hard-hearted to scroll past without laying a comment at each freshly dug cyber-mound, even when one has no personal relationship with the deceased, or, to large degree, the owner. The lazy man may “like” news of a beloved Airedale’s demise, but acknowledgment cannot always be said to equal respect.

And what, pray tell, is the protocol after? How many minutes should elapse before it is acceptable to post Throwback Thursday shots of one’s younger, big-haired self? What if one accidentally sends a Farmville notification to the bereaved?

If only we had a Victorian we could ask.

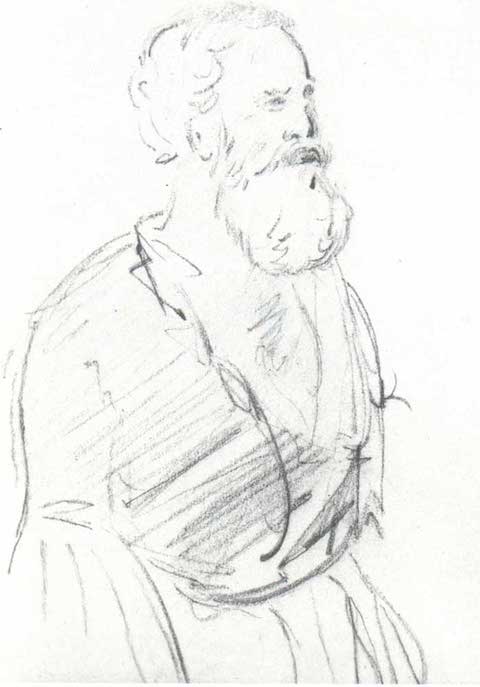

Preferably, Charles Dickens.

He went to his reward eleven years before “Poor Cherry,” the first dog planted in Hyde Park’s small pet cemetery, but he was a keen observer of mourning customs.

He was also an animal lover, as his daughter, Mamie noted in My Father as I Recall Him:

On account of our birds, cats were not allowed in the house; but from a friend in London I received a present of a white kitten — Williamina — and she and her numerous offspring had a happy home at “Gad’s Hill.” … As the kittens grow older they became more and more frolicsome, swarming up the curtains, playing about on the writing table and scampering behind the bookshelves. But they were never complained of and lived happily in the study until the time came for finding them other homes. One of these kittens was kept, who, as he was quite deaf, was left unnamed, and became known by servants as “the master’s cat,” because of his devotion to my father. He was always with him, and used to follow him about the garden like a dog, and sit with him while he wrote. One evening we were all, except father, going to a ball, and when we started, left “the master” and his cat in the drawing-room together. “The master” was reading at a small table, on which a lighted candle was placed. Suddenly the candle went out. My father, who was much interested in his book, relighted the candle, stroked the cat, who was looking at him pathetically he noticed, and continued his reading. A few minutes later, as the light became dim, he looked up just in time to see puss deliberately put out the candle with his paw, and then look appealingly towards him. This second and unmistakable hint was not disregarded, and puss was given the petting he craved. Father was full of this anecdote when all met at breakfast the next morning.

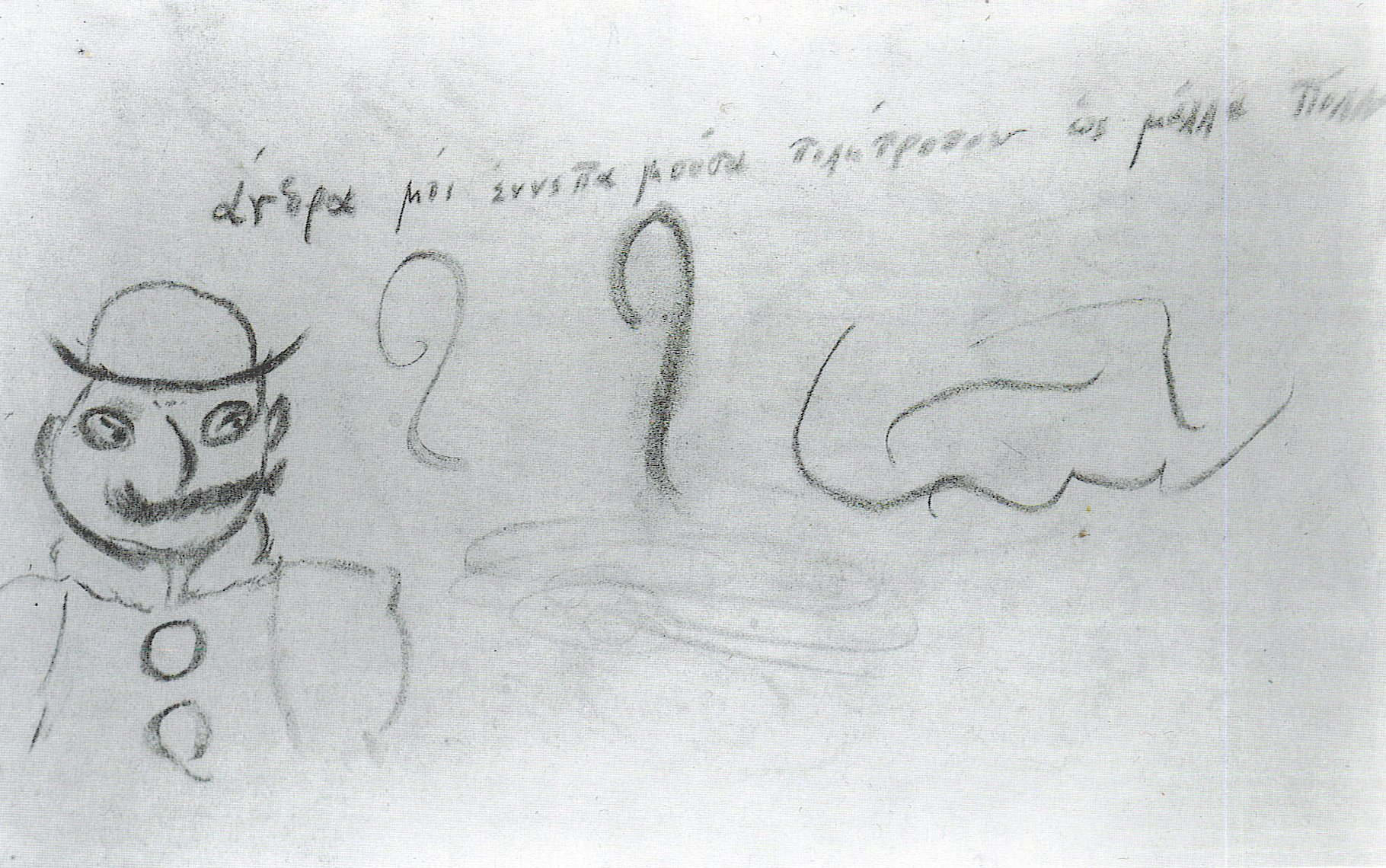

One anecdote Mamie chose not to include is that when Dickens’ Bob, the deaf kitten mentioned above, left this earthly plane, the master turned him into a letter opener.

Well, not the whole cat, actually. Just a single paw, which the author had stuffed and attached to an ivory blade. The blade is engraved “C.D. In Memory of Bob 1862” which is more grave marker than most pussycats can hope for.

Should anyone ever publish a History of Charles Dickens in 100 Objects, count on this object to make the cut.

Still, it’s an oddity most contemporary Westerners would view with distaste. (But not all. The Morbid Anatomy Museum’s frequent small mammal taxidermy workshops draw mightily from the ranks of Brooklyn hipsters.)

I certainly felt the need to hustle my then 12-year-old son past this unusual souvenir when it was displayed as part of the New York Public Library’s cozy exhibit, Charles Dickens: The Key to Character. The kid’s an animal lover who was in Oliver! at the time. I feared he’d respond with Tale of Two Cities-level peasant rage, which is acceptable, except when there’s a show that must go on.

Preserved!, a British taxidermy blog sponsored by the Arts and Humanities Research Council offers a tender take on Dickens’ motivation. Over the years, he had several animals, including a pet raven, stuffed, but his closeness with Bob called for a special approach. 19th-century literature scholar Jenny Pyke writes that “the taxidermied cat paw stands out in its tactile softness and emotional tenderness. Most often, as popular as it was in the nineteenth century, taxidermy was consumed visually only, displayed in glass cases or crowded cabinets. With Bob’s paw, Dickens created an object meant to be held daily.”

It’s not for the squeamish, but I can see how this cannily orchestrated hand-holding could bring ongoing comfort. More than the fleeting condolences proliferating on Facebook, anyway.

Related Content:

Charles Dickens’ Hand-Edited Copy of His Classic Holiday Tale, A Christmas Carol

T.S. Eliot Reads Old Possum’s Book of Practical Cats & Other Classic Poems (75 Minutes, 1955)

Ayun Halliday is an author, homeschooler, and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Follow her @AyunHalliday