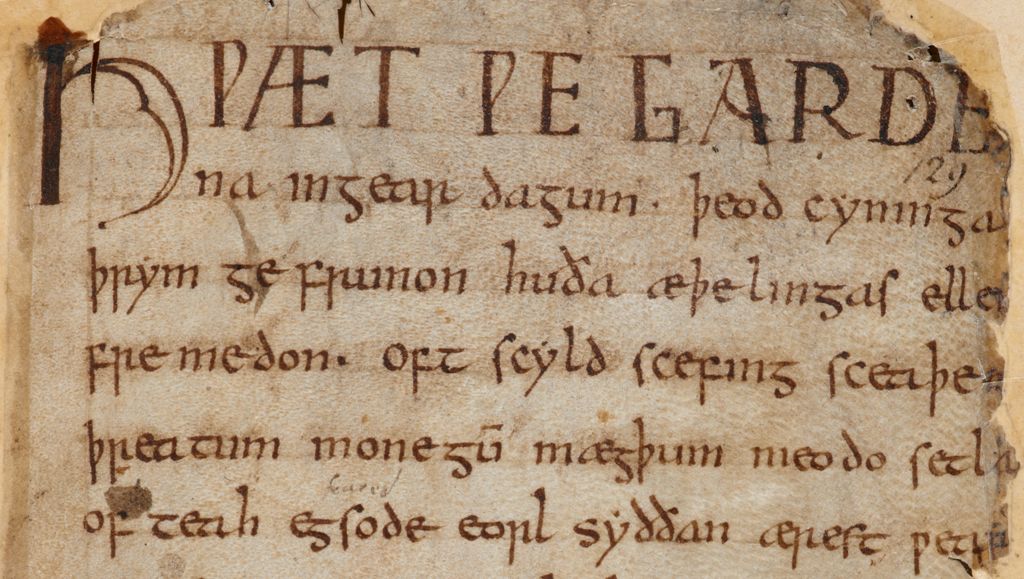

I still remember the thrill I felt when I happened upon a set of the complete Sherlock Holmes stories at an antique store. For a mere ten dollars, I acquired handsomely bound, suitably patina-of-age-bearing editions of each and every one of the sleuth of 221B Baker Street’s adventures that Sir Arthur Conan Doyle ever wrote. In addition to this thrill, I also got a few surprises: first that all of those stories combined — the stories that made Holmes and his assistant Dr. John Watson into household names of nearly 130 years’ standing — fit into two not-especially-large books; second, that Holmes solved his mysteries not just in 56 short stories but four novels as well; and third, that many of those short stories and novels differed intriguingly in tone and content from my expectations. So many modern adaptations — all those television series up to the BBC’s new and expensive-looking Sherlock, the early CD-ROM computer game, Hayao Miyazaki’s steampunk animation Sherlock Hound, Guy Ritchie’s Robert Downey Jr.-showcasing Hollywood films — have convinced us we “know” Sherlock Holmes, which makes it all the more fascinating to investigate, as it were, the original literature.

These days, especially given the recent ruling (just re-affirmed by the Supreme Court) that Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes stories “are no longer covered by United States copyright law and can be freely used by creators without paying any licensing fee to the Conan Doyle estate,” you can download the complete Sherlock Holmes canon in a variety of ebook formats, from PDF to ePub to ASCII to MOBI for Kindle. If you prefer listening to reading, Librivox has made available three different versions of Sherlock Holmes in audiobook form. However you choose technologically to experience the Sherlock Holmes canon, I recommend taking it on chronologically, beginning with the 1887 novel A Study in Scarlet — less a mystery, to my mind, than the scary tale of a murderous Mormon sect — to 1927’s “The Adventure of Shoscombe Old Place,” Holmes’ final Conan Doyle-penned adventure. Somewhere in the middle — in 1893’s “The Final Problem,” to be precise — Holmes’ creator tried to kill the beloved detective off, but the reading public would have none of it. What about Sherlock Holmes stories had got them so hooked that they could successfully demand a resurrection? Now you, too, can find out, without even having to spend the ten dollars, let alone go to the antique store.

Bonus: Below, you can listen to The New Adventures of Sherlock Holmes, an old-time radio show that aired in the US from October 2, 1939 to July 7, 1947.

Related Content:

Sherlock Holmes Is Now in the Public Domain, Declares US Judge

Arthur Conan Doyle Discusses Sherlock Holmes and Psychics in a Rare Filmed Interview (1927)

Arthur Conan Doyle Fills Out the Questionnaire Made Famous By Marcel Proust (1899)

1,000 Free Audio Books: Download Great Books for Free 800 Free eBooks for iPad, Kindle & Other DevicesColin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture and writes essays on cities, language, Asia, and men’s style. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.