Remember when television was the big gorilla poised to put an end to all reading?

Then along came the miracle of the Internet. Blogs begat blogs, and thusly did the people start to read again!

Of course, many a great newspaper and magazine fell before its mighty engine. So it goes.

So did television in the old fashioned sense. So it goes.

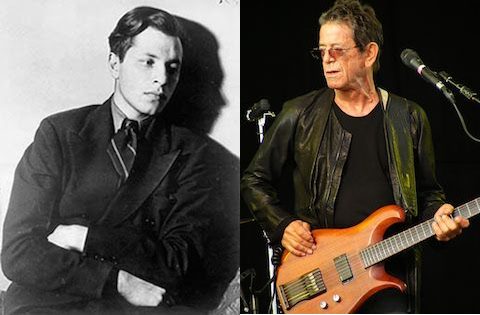

Funny to think that these fast-moving developments weren’t even part of the landscape in 1991, when author Kurt Vonnegut swung by his hometown of Indianapolis to appear on the local program, Across Indiana.

Host Michael Atwood pointed out the irony of a television interviewer asking a writer if television was to blame for the decline in reading and writing. After which he listened politely while his guest answered at length, comparing reading to an acquired skill on par with “ice skating or playing the French horn.”

Gee… irony elicits a more frenetic approach in the age of BuzzFeed, Twitter, and YouTube. (Nailed it!)

Irony and humanity run neck and neck in Vonnegut’s work, but his appreciation for his Hoosier upbringing was never less than sincere:

When I was born in 1922, barely a hundred years after Indiana became the 19th state in the Union, the Middle West already boasted a constellation of cities with symphony orchestras and museums and libraries, and institutions of higher learning, and schools of music and art, reminiscent of the Austro-Hungarian Empire before the First World War. One could almost say that Chicago was our Vienna, Indianapolis our Prague, Cincinnati our Budapest and Cleveland our Bucharest.

To grow up in such a city, as I did, was to find cultural institutions as ordinary as police stations or fire houses. So it was reasonable for a young person to daydream of becoming some sort of artist or intellectual, if not a policeman or fireman. So I did. So did many like me.

Such provincial capitals, which is what they would have been called in Europe, were charmingly self-sufficient with respect to the fine arts. We sometimes had the director of the Indianapolis Symphony Orchestra to supper, or writers and painters, and architects like my father, of local renown.

I studied clarinet under the first chair clarinetist of our orchestra. I remember the orchestra’s performance of Tchaikovsky’s 1812 Overture, in which the cannons’ roars were supplied by a policeman firing blank cartridges into an empty garbage can. I knew the policeman. He sometimes guarded street crossings used by students on their way to or from School 43, my school, the James Whitcomb Riley School.

Vonnegut’s views were shaped at Shortridge High School, where he numbered among the many not-yet-renowned writers honing their craft on The Daily Echo. Thought he didn’t bring it up in the video above, the Echo also yielded his nickname: Snarf.

Vonnegut agreed with interviewer Atwood that the daily practice of keeping a journal is an excellent discipline for beginning writers. He also considered journalistic assignments a great training ground. He made a point of mentioning that Mark Twain and Ring Lardner got their starts as newspaper reporters. It may be harder for aspiring writers to find paying work these days, but the Internet is replete with opportunities for those who crave a daily assignment.

It’s also overflowing with bullet pointed lists on how to become a writer, but if you’re like me, you’ll prefer to receive this advice from Vonnegut, himself, on a set festooned with farming implements, quilts, and dipped candles.

The interview continues in the remaining parts:

Part 2

Part 3

Part 4

Related Content:

Kurt Vonnegut Reads Slaughterhouse-Five

Kurt Vonnegut: Where Do I Get My Ideas From? My Disgust with Civilization

Kurt Vonnegut Explains “How to Write With Style”

Kurt Vonnegut Diagrams the Shape of All Stories in a Master’s Thesis Rejected by U. Chicago

Ayun Halliday is an author, homeschooler, and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Like Vonnegut, she’s a native of Indianapolis, and her mother was the editor of the Short Ridge Daily Echo. Follow her @AyunHalliday