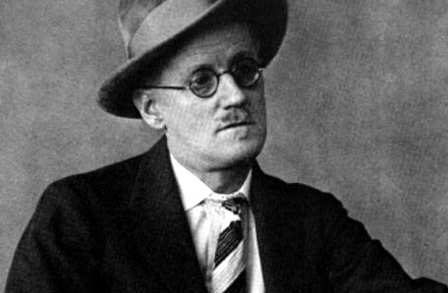

In 1977, erudite Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges delivered a series of seven lectures in Buenos Aires on a variety of topics, including Dante’s Divine Comedy, nightmares, and the Kabbalah. (The lecture series is collected in an English translation entitled Seven Nights.) One of the lectures is simply called “Buddhism,” and in it, Borges presents an overview of the ancient Eastern religion. Borges had previously made scattered reference to Buddhist subjects in his writing, though he certainly never devoted as much attention to it as he did Catholicism or Judaism, a faith and heritage he found endlessly fascinating and admirable.

His portrait of Buddhism, though much less in depth, is no less sympathetic. The lecture is adapted, it seems, from a short book written the previous year, Qué es el Budismo?, a “clear and concise explanation of the religion, its value systems, and how some of its principal teachings share some similarities with other faiths.” So writes the blog Vaguely Borgesian, who also comment that Borges’ book—and by extension the lecture—“rarely goes beyond what one might find on say a Wikipedia article on Buddhism.” That may be so, but—as we can see in this English translation of Borges’ lecture—the author does several times during his summary offer some distinctly Borgesian commentary of his own. Below are just a few excerpts:

Buddism’s Tolerance:

[Buddhism’s] longevity can be explained for historical reasons, but such reasons are fortuitous or, rather, they are debatable, fallible. I think there are two fundamental causes. The first is Buddhism’s tolerance. That strange tolerance does not correspond, as is the case with other religions, to distinct epochs: Buddism was always tolerant.

It has never had recourse to steel or fire, has never thought that steel or fire were persuasive…. A good Buddhist can be Lutheran, or Methodist, or Calvinist, or Sintoist, or Taoist, or Catholic; he can be a proselyte to Islam or Judaism, with complete freedom. But it is not permissible for a Christian, a Jew or a Muslim to be a Buddhist.

On the Historical Existence of the Buddha:

We may disbelieve this legend. I have a Japanese friend, a Zen Buddhist, with whom I have had long and friendly arguments. I told him that I believed in the historic truth of Buddha. I believed and I believe that two thousand five hundred years ago there was a Nepalese prince called Siddharta or Gautama who became the Buddha, that is, the Awoken, the Lucid One – as opposed to us who are asleep or who are dreaming this long dream which is life. I remember one of Joyce’s phrases: “History is a nightmare from which I want to awake.” Well then, Siddharta, at thirty years of age, awoke and became Buddha.

On Buddhism and Belief:

The other religions demand much more credulity on our part. If we are Christians we must believe that one of the three persons of the Divinity condescended to become a man and was crucified in Judea. If we are Muslims we must believe that there is no other god than God and that Mohammad is his apostle. We can be good Buddhists and deny that Buddha existed. Or, rather, we may think, we must think that our belief in history isn’t important: what is important is to believe in the Doctrine. Nevertheless, the legend of Buddha is so beautiful that we cannot help but refer to it.

Borges has much more to say in the full lecture on Buddhist cosmology and history. He concludes with the very respectful statement below:

What I have said today is fragmentary. It would have been absurd for me to have expounded on a doctrine to which I have dedicated many years – and of which I have understood little, really – with a wish to show a museum piece. Buddhism is not a museum piece for me: it is a path to salvation. Not for me, but for millions of people. It is the most widely held religion in the world and I believe that I have treated it with respect when explaining it tonight.

To learn more about Borges and Buddhism, see this article, and the watch the video above, a short introduction to a lecture course given by Borges’ friend Amelia Barili at UC Berkeley.

Related Content:

Jorge Luis Borges’ 1967–8 Norton Lectures On Poetry (And Everything Else Literary)

Jorge Luis Borges’ Favorite Short Stories (Read 7 Free Online)

Borges Explains The Task of Art

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness