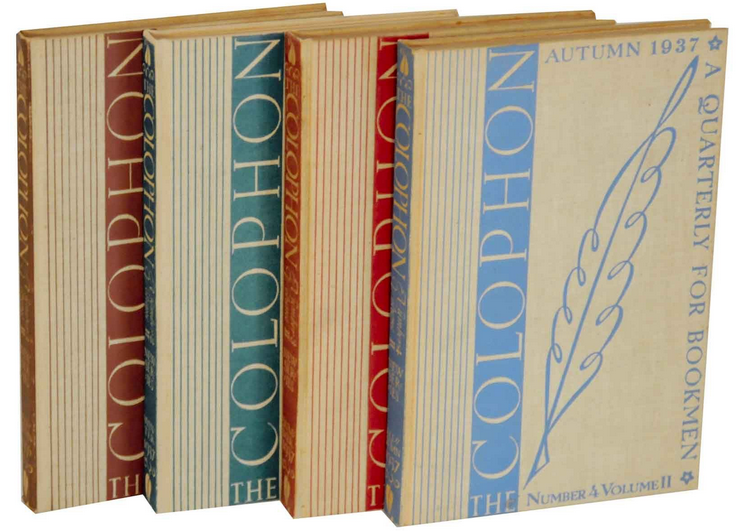

Few know as much about our incompetence at predicting our own future as Matt Novak, author of the site Paleofuture, “a blog that looks into the future that never was.” Not long ago, I interviewed him on my podcast Notebook on Cities and Culture; ever since, I’ve invariably found out that all the smartest dissections of just how little we understand about our future somehow involve him. And not just those — also the smartest dissections of how little we’ve always understood about our future. Take, for example, the year 1936, when, in Novak’s words, “a quarterly magazine for book collectors called The Colophon polled its readers to pick the ten authors whose works would be considered classics in the year 2000.” They named the following:

- Sinclair Lewis

- Willa Cather

- Eugene O’Neill

- Edna St. Vincent Millay

- Robert Frost

- Theodore Dreiser

- James Truslow Adams

- George Santayana

- Stephen Vincent Benét

- James Branch Cabell

At first glance, this list might not look so embarrassing. Nobel laureate Sinclair Lewis remains oft-referenced, if much more so for Babbitt (Kindle + Other Formats – Read Online Now), his 1922 indictment of a business-blinkered America, than for It Can’t Happen Here, his bestselling Hitler satire from the year before the poll. Most Americans passing through high school English still bump into Willa Cather, Robert Frost (four of whose volumes you can find in our collection Free eBooks), and perhaps Eugene O’Neill (likewise) and Theodore Dreiser (especially through Sister Carrie: Kindle + Other Formats – Read Online Now) as well.

Some of us may also remember Stephen Vincent Benét’s epic Civil War poem John Brown’s Body from our school days, but it would take a well-read soul indeed to nod in agreement with such selections as New England historian James Truslow Adams and now little-read (though once Sinclair- and Dreiser-acclaimed) fantasist James Branch Cabell. The well-remembered George Santayana still looks like a judgment call to me, but what of absent famous names like F. Scott Fitzgerald, William Faulkner, Ernest Hemingway, or maybe James Joyce? The Colophon’s editors included Hemingway on their own list, but which writers do you think stand as the Fitzgeralds and Faulkners of today — or, more to the point, of the year 2078? Care to put your guess on record? Feel free to make your predictions in the comments section below.

via @ElectricLit/Smithsonian

Related Content:

The 10 Greatest Books Ever, According to 125 Top Authors (Download Them for Free)

The 25 Best Non-Fiction Books Ever: Readers’ Picks

600 Free eBooks for iPad, Kindle & Other Devices

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture and writes essays on cities, language, Asia, and men’s style. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.