According to Ted Morgan, author of William S. Burroughs biography Literary Outlaw (which Burroughs hated), the hard-living Beat writer added “teacher” to the list of jobs he did not like after an unhappy semester teaching creative writing at the City College of New York. He complained about dimwitted students, and disliked the job—arranged for him by Allen Ginsberg—so much that he later turned down a position at the University of Buffalo that paid $15,000 a semester, even though he desperately needed the money. That Burroughs had recently kicked heroin may have contributed to his unease with the prosaic regularities of college life. Whatever the story, he later remarked that the “teaching gig was a lesson in never again.”

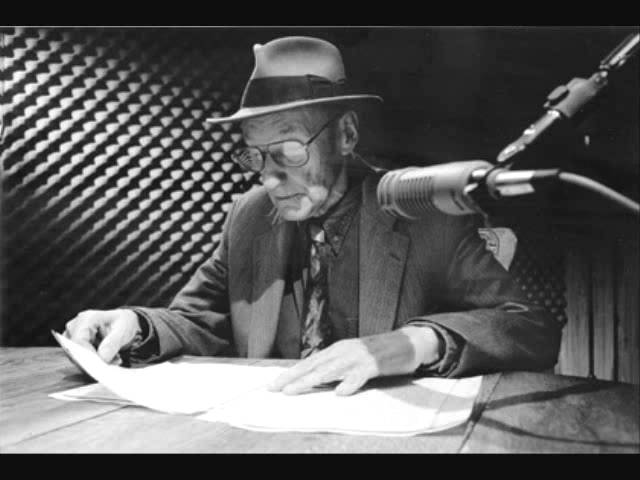

What then could have lured Burroughs out to Boulder Colorado five years later to deliver a series of lectures on creative writing at Naropa University? He’d picked up his heroin habit again, and his friendship with Ginsberg—who co-founded Naropa’s writing program—must have played a part. Whatever the reasons, this assignment differed greatly from his City College stint: no student writing, no office hours or admin. Just Burroughs doing what came naturally—holding court, on literature, parapsychology, occult esoterica, violence, aliens, neuroscience, and his own novels Naked Lunch and The Soft Machine.

Burroughs’ lectures are heavily philosophical, which might have turned off his New York students, but surely turned on his Naropa audience. And if you stopped to listen, it will probably turn you on too, in ways creative and intellectual. Ostensibly on the subject of creative reading, Burroughs also offers creative writing instruction in each talk. His discussions of writers he admires—from Carson McCullers to Aleister Crowley to Stephen King—are fascinating, and he uses no shortage of examples to illustrate various writing techniques. Fortunately for us, the lectures were recorded. Says Dangerous Minds, who provide helpful descriptions of each lecture: “now you can have your very own creative writing class from William S. Burroughs, all thanks to the wonders of YouTube.” Hear all three lectures above, and be by turns inspired, instructed, enlightened, and warped.

You can find Burrough’s lectures on Creative Reading listed in our collection of Free Online Literature Courses, part of our larger collection, 1,700 Free Online Courses from Top Universities.

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. It’s a great way to see our new posts, all bundled in one email, each day.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

Related Content:

William S. Burroughs on the Art of Cut-up Writing

William S. Burroughs Reads His Controversial 1959 Novel Naked Lunch

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness