Image by Steve Rhodes, via Wikimedia Commons

Like many David Foster Wallace fans, I bought a copy of J. Peder Zane’s The Top Ten (previously featured here), a compilation of various famous writers’ top-ten-books lists, expressly for DFW’s contribution. Like most of those David Foster Wallace fans, I felt more than a little surprised when I turned to his page and found out which ten books he’d chosen. Here, as quoted in the Christian Science Monitor, we have the Infinite Jest author and widely recognized (if reluctant) “high-brow” literary figure’s top ten list:

1. The Screwtape Letters, by C.S. Lewis

2. The Stand, by Stephen King

3. Red Dragon, by Thomas Harris

4. The Thin Red Line, by James Jones

5. Fear of Flying, by Erica Jong

6. The Silence of the Lambs, by Thomas Harris

7. Stranger in a Strange Land, by Robert A. Heinlein

8. Fuzz, by Ed McBain

9. Alligator, by Shelley Katz

10. The Sum of All Fears, by Tom Clancy

Thrillers, killers, and a dose of Christianity to top it off; I didn’t blame Zane when he asked, “Is he serious? Beats me. To be honest, I don’t know what Wallace was thinking. But I do think there’s a certain integrity to his list.” Wallace himself seemed to read assiduously all over the map — or, more to the point, all up and down the scale of critical respectability. Rattling off “the stuff that’s sort of rung my cherries” to Salon’s Laura Miller in 1996, for a contrast, he named, among other worthy reads, Socrates’ funeral oration, John Donne, “Keats’ shorter stuff,” Schopenhauer, William James’ Varieties of Religious Experience, Wittgenstein’s Tractatus, Joyce’s Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, Hemingway’s In Our Time, Don DeLillo, A.S. Byatt, Cynthia Ozick, Donald Barthelme, Moby-Dick, and The Great Gatsby. (You can find many of these texts in our Free eBooks collection.)

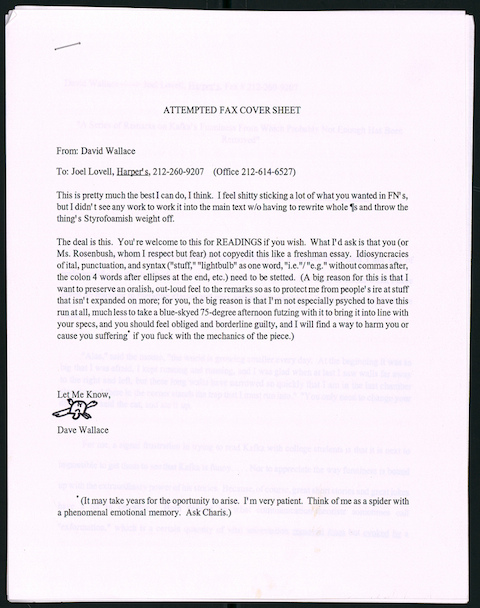

That, some Wallace readers may think, sounds more like it. But those who’ve paid close attention to Wallace’s language — that often breathlessly but hopelessly imitated mixture of high-caliber vocabulary, casually spoken rhythm, deceptively sharp-edged perception, shrugging presentation, and deliberate solecism — know how fully he simultaneously embodied both “high” and “low” English writing. Just look at the Literary Analysis syllabus from his days teaching at Illinois State University, which demands students read not just The Silence of the Lambs but another Thomas Harris novel, Black Sunday, as well as more C.S. Lewis (in this case The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe) and Stephen King (Carrie). Lest you doubt his commitment to the serious reading of popular fiction, note the presence of Jackie Collins’ Rock Star. In the classroom and in life, Wallace must truly have believed that there exists no low fiction; just low ways of reading fiction.

Looking for free, professionally-read audio books from Audible.com? Here’s a great, no-strings-attached deal. If you start a 30 day free trial with Audible.com, you can download two free audio books of your choice. Get more details on the offer here.

Related Content:

David Foster Wallace’s Love of Language Revealed by the Books in His Personal Library

30 Free Essays & Stories by David Foster Wallace on the Web

David Foster Wallace: The Big, Uncut Interview (2003)

David Foster Wallace’s 1994 Syllabus

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture and writes essays on cities, Asia, film, literature, and aesthetics. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on his brand new Facebook page.