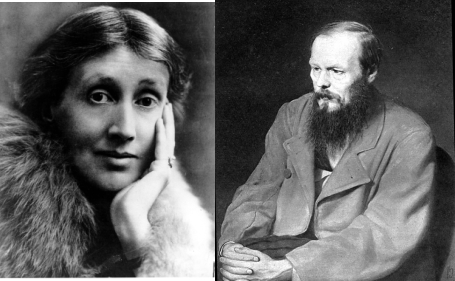

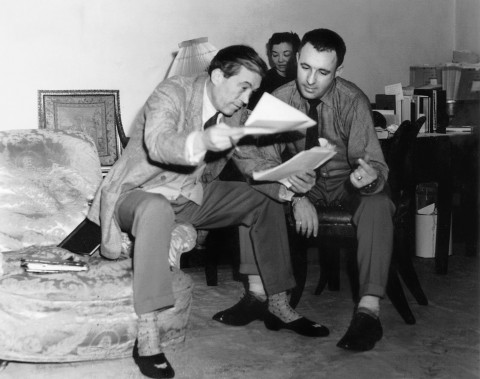

John Steinbeck had the literary voice of an American preacher. Not a New England Calvinist, all cold reasoning, nor a Southern Pentecostal, all fiery feeling, but a California cousin, the many generations traveling westward having produced in him both hunger and vision, so that grandiosity is his natural idiom, restless, unfulfilled desire his natural tone. His themes, certainly Biblical; his characters, salt of the earth tradesmen, nomads, the lame and the halt. But his syntax always spoke of vastness, of a God-like universe emptied of all gods. And so, when Steinbeck won the Nobel Prize in 1962, his speech rang of a humanist sermon carved on stone tablets. (Above, as he reads, it’s hard not to see him as Vincent Price, a look he acquired in his final years.)

At times, I must admit, it’s not great. Or, rather, it’s a strange, uneven speech. Where Steinbeck the novelist is in full command of his bombast, Steinbeck the speechwriter sounds at times like he pieced things together in his hotel room the night before with only his Gideon as a reference. Ah, but Steinbeck at 4 in the morning exceeds what most of us could do at anytime if asked to speak on such a subject as “the nature and direction of literature,” which he says is customary for one in his position. Steinbeck decides to change the task and instead discuss no less than “the high duties and responsibilities of the makers of literature.” Perhaps a more manageable topic. He speaks of the writer’s mission not as a priestcraft of words, but as a guardianship of something even older, “as old as speech.” He invokes “the skalds, the bards, the writers,” but of the priests who came later, he has no kind words:

Literature was not promulgated by a pale and emasculated critical priesthood singing their litanies in empty churches—nor is it a game for the cloistered elect, the tin-horn mendicants of low-calorie despair.

The critic in me winces, but the reader in me thrills. After a few clunkers in his opening (something about a mouse and a lion), he has turned on the judgment, and it’s good. This is the Steinbeck we love, who makes us look through a god’s eye view telescope, then turns it around and shows us the other end. Then it’s gone, the scale, the enormity, the fantastic morality play. He gets a little vague on Faulkner, mentions some reading he’d just done on Alfred Nobel. And as you begin to suspect he’s going to tell us about his summer vacation, he erupts into a glorious finale of groundshaking fireworks worthy of comparison to the Nobel invention’s most fearsome cold war progeny.

Less than fifty years after [Nobel’s] death, the door of nature was unlocked and we were offered the dreadful burden of choice.

We have usurped many of the powers we once ascribed to God.

Fearful and unprepared, we have assumed lordship over the life or death of the whole world—of all living things.

The danger and the glory and the choice rest finally in man. The test of his perfectibility is at hand.

Having taken Godlike power, we must seek in ourselves for the responsibility and the wisdom we once prayed some deity might have.

Man himself has become our greatest hazard and our only hope.

So that today, St. John the apostle may well be paraphrased: In the end is the Word, and the Word is Man—and the Word is with Men.

I think St. John would be proud of the vehicle, if not at all the tenor. But unlike John Steinbeck, he never saw the war that gave us Auschwitz and Hiroshima. Read the full text of Steinbeck’s speech at the Nobel Prize site here.

Related Content:

“Nothing Good Gets Away”: John Steinbeck Offers Love Advice in a Letter to His Son (1958)

William Faulkner Reads His Nobel Prize Speech

On His 100th Birthday, Hear Albert Camus Deliver His Nobel Prize Acceptance Speech (1957)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness