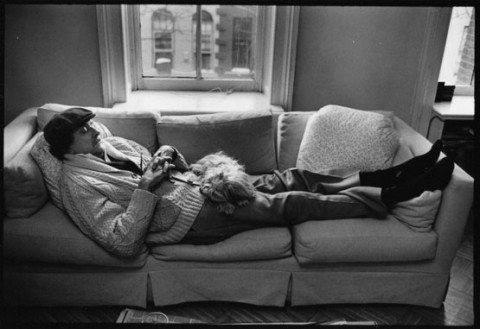

Courtesy of New York Social Diary, here is a lovely series of photographs featuring famous authors and their dogs. If you’ve ever wondered which breeds have served as muse to William Styron, Stephen King, William F. Buckley, Kurt Vonnegut, then this collection is for you. But be warned: We’re still recovering from the sight of that Lhasa Apso flopped on Vonnegut’s lap–we were hoping for a wolfhound.

For more artist-canine combinations, Flavorwire has rounded up a collection of musicians and their dogs. Unlike the authors, these owners really do look like their pets. (See Robert Plant.)

via @brainpicker and The Millions

Sheerly Avni is a San Francisco-based arts and culture writer. Her work has appeared in Salon, LA Weekly, Mother Jones, and many other publications. You can follow her on twitter at @sheerly.