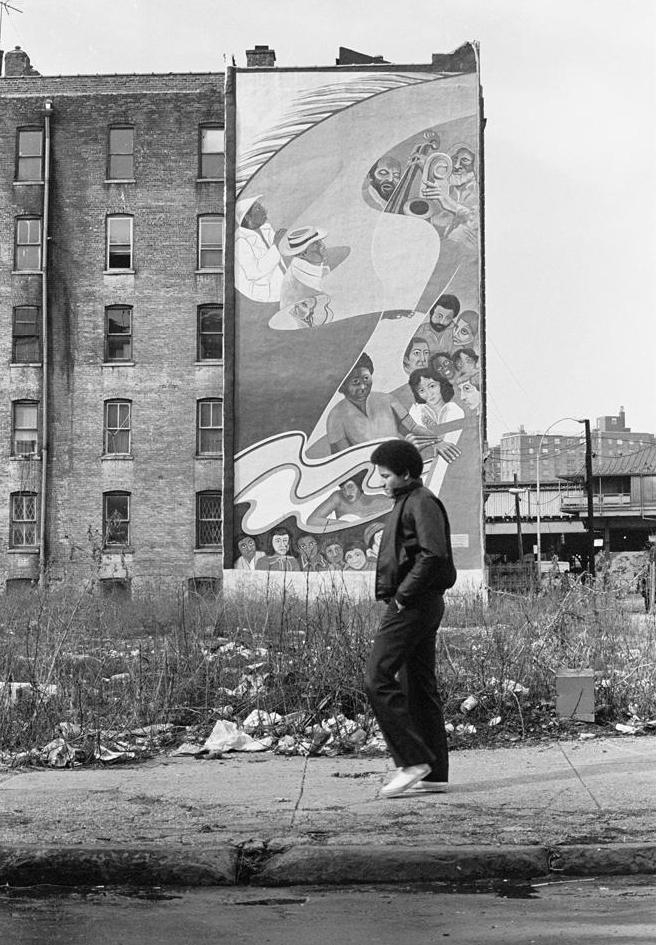

The music and the culture of hip-hop are inseparable from the Bronx, Queens, Harlem, and Brooklyn, NY. And now that the form is a global culture that exists in online spaces as much as it does where people meet and shake hands, its documentary history may be more valuable than ever. Hip-Hop began, unquestionably, as a regional phenomenon, and its formal qualities always bear the traces of its matrix, a confluence of African-American, Caribbean, and Latin American socio-cultural experiences and creative streams, meeting with new consumer audio technology and a drive toward countercultural experiments that took hold all over New York amidst the urban decay of the 70s.

Photo by Joe Conzo, Jr.

We know the story in broad strokes. Now we can immerse ourselves in the daily life, so to speak, of early hip hop, thanks to a partial digitization of Cornell University’s vast hip hop collection. The physical collection, housed in Ithaca New York, contains “hundreds of party and event flyers ca. 1977–1985; thousands of early vinyl recordings, cassettes and CDs; film and video; record label press packets and publicity; black books, photography, magazines, books, clothing, and more.”

Photo by Joe Conzo, Jr.

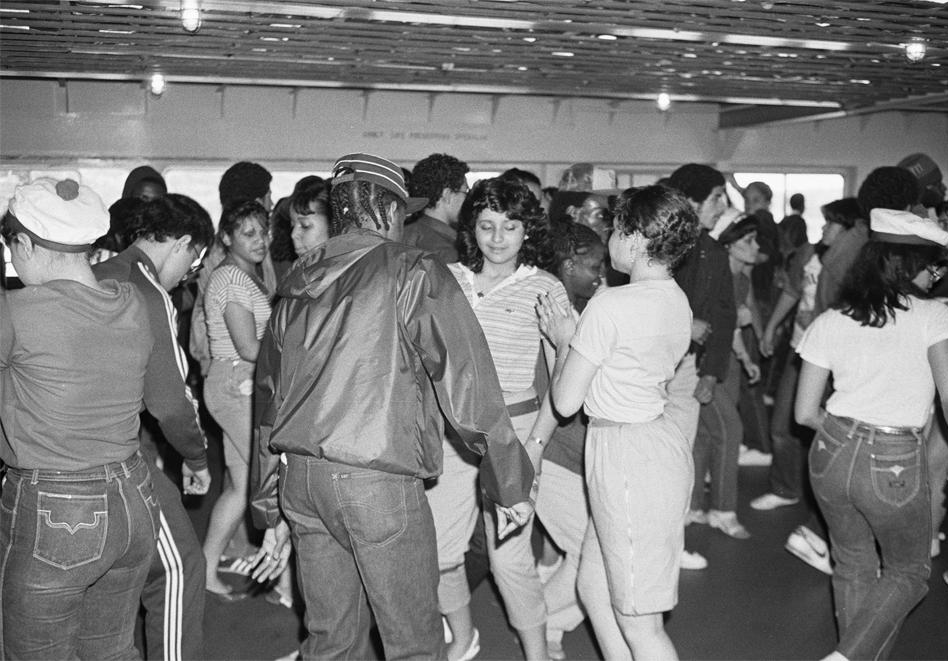

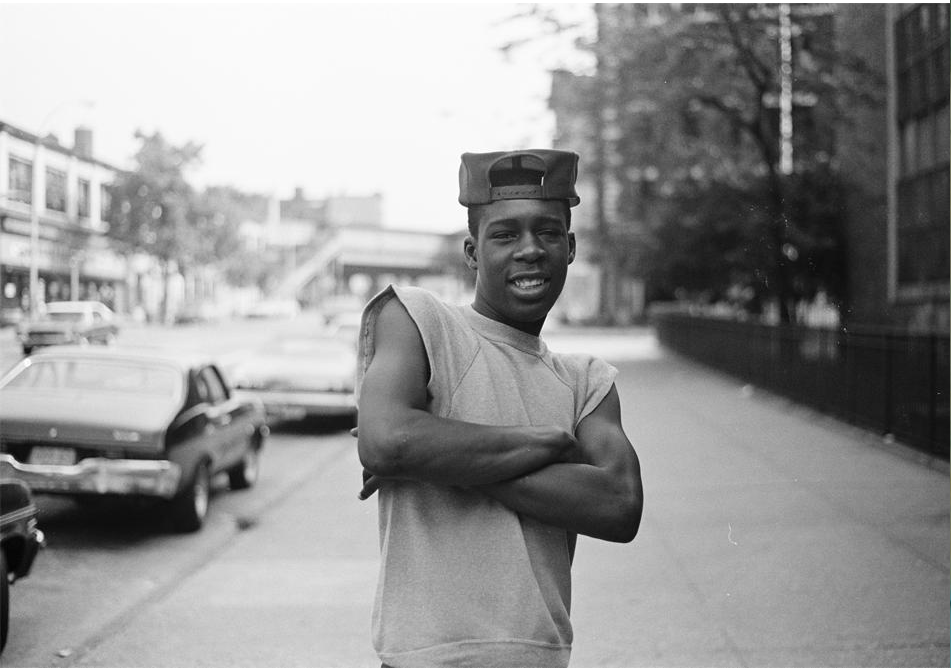

While this impressive trove of physical artifacts is open to the public, most of us won’t ever make the journey. But whether we’re fans, scholars, or curious onlookers, we can benefit from its curatorial largesse through online archives like that of Joe Conzo, Jr., who “captured images of the South Bronx between 1977 and 1984, including early hip hop jams, street scenes, and Latin music performers and events.”

Photo by Joe Conzo, Jr.

While still in high school, Conzo became the official photographer for the early influential rap group the Cold Crush Brothers. The position gave him unique access to the “localized, grassroots culture about to explode into global awareness.” Cornell’s site remarks that “without Joe’s images, the world would have little idea of what the earliest era of hip hop looked like, when fabled DJ, MC, and b‑boy/girl battles took place in parks, school gymnasiums and neighborhood discos.”

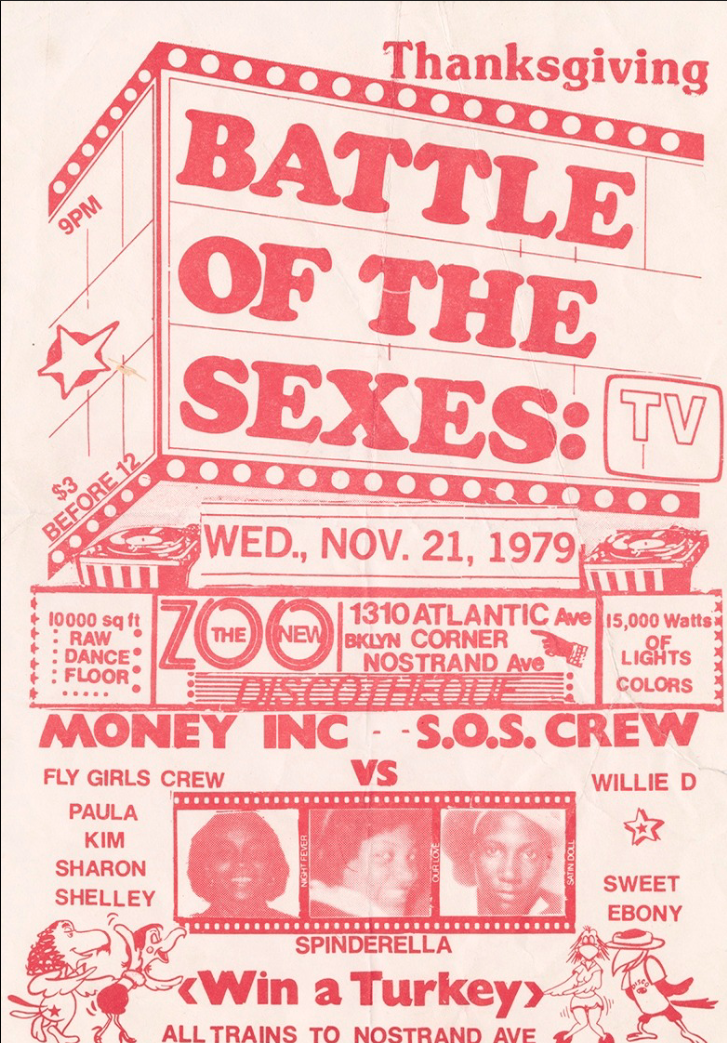

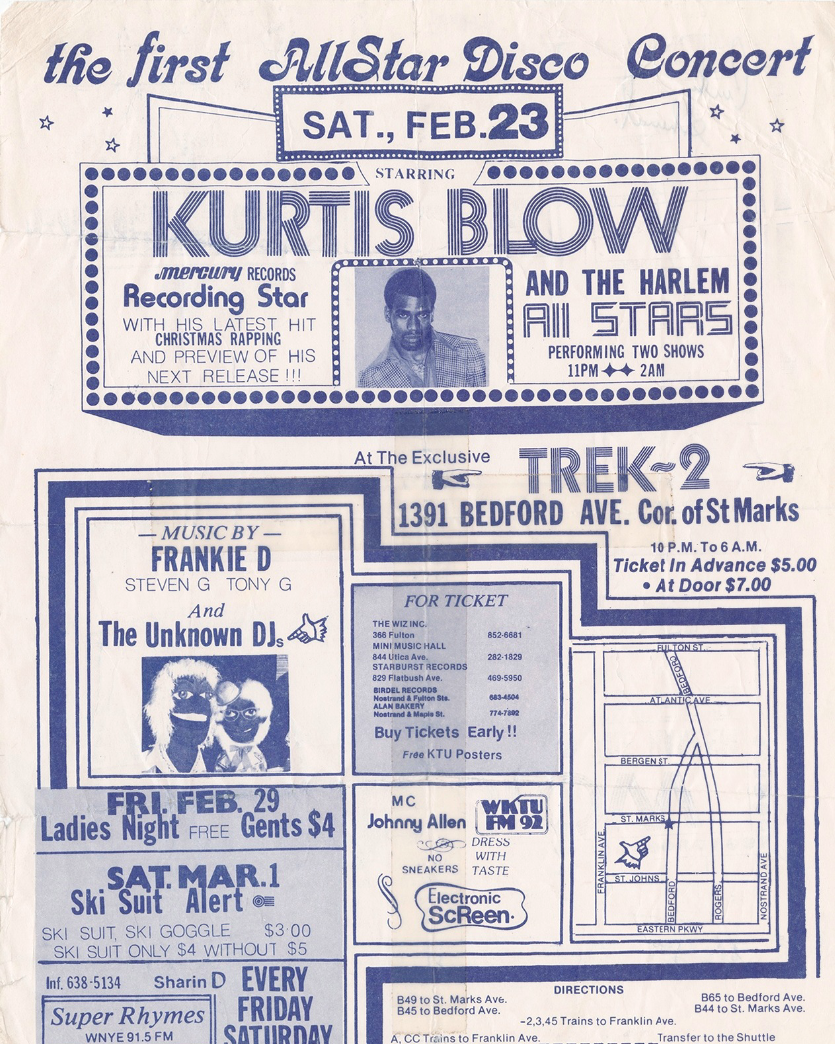

Another of Cornell’s collections, the Buddy Esquire Party and Event Flyer Archive, preserves over 500 such artifacts, the “largest known institutional collection of these scarce flyers, which have become increasingly valued for the details they provide about early hip hop culture.” Local, grassroots scenes like this one seem increasingly rare in a globalized, always-online 21st century. Archives like Cornell’s not only tell the story of such a culture, but in so doing they document a critical period in New York City, much like punk or jazz archives tell important histories of London, New York, D.C., Paris, New Orleans, etc.

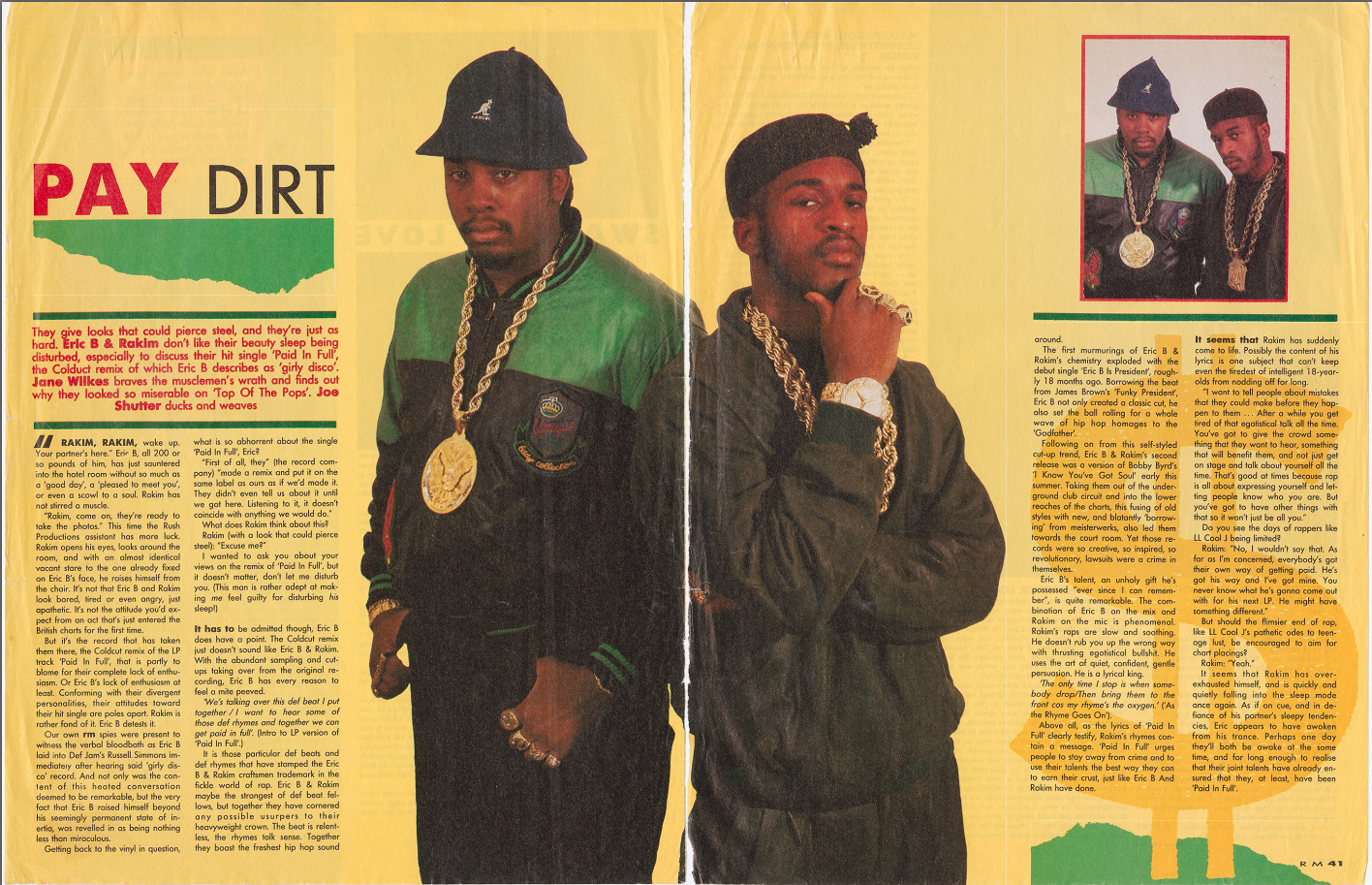

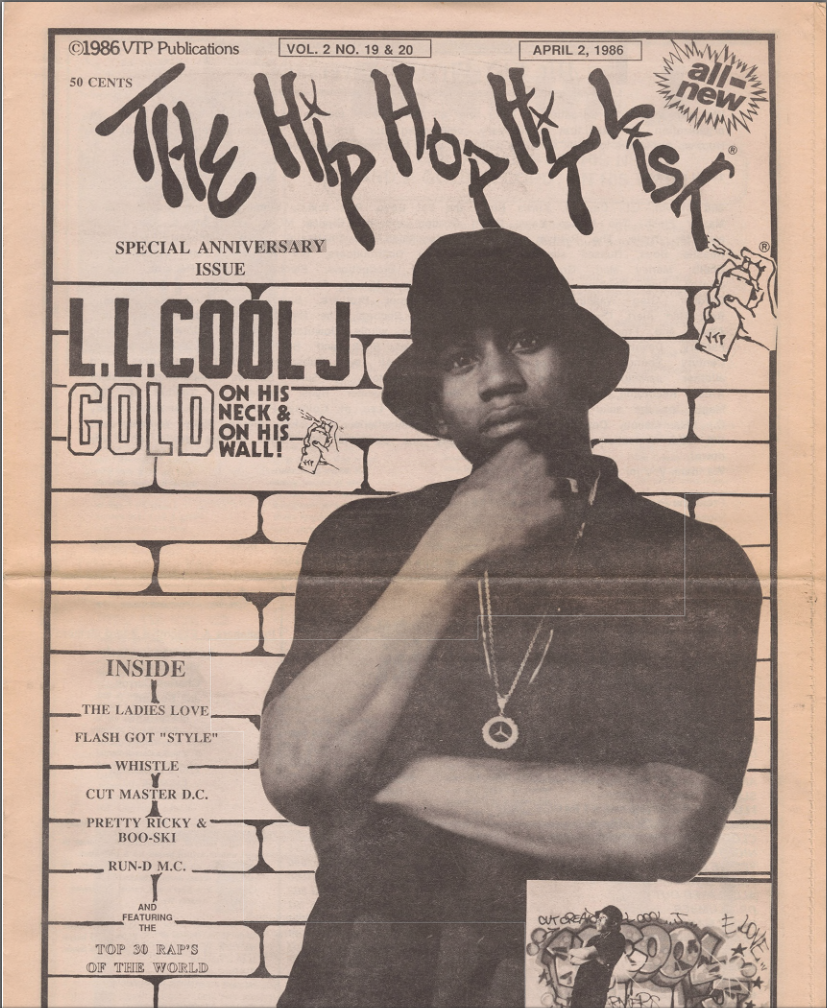

The third digital collection hosted by Cornell, the Adler Hip Hop Archive, comes from journalist and Def Jam Recordings publicist Bill Adler. The materials here naturally skew toward the industry side of the culture, documenting its leap from the New York streets to “global awareness” and a spread to cities nationwide, through magazine photo spreads, ads, promotional pics, press clippings, and much more.

Some of these collections are easier to navigate than others—you’ll have to wade through many non-hip-hop photos in the huge Joe Conzo, Jr. archive, though most of them, like his Puerto Rican portraits and landscapes for example, are of interest in their own right. Conzo’s photo journalism of the Bronx in the late 70s and 80s has all the intimacy and candor of a family album or collection of yearbook pictures—charmingly awkward, exuberant, and a stark contrast to the high-profile glamour of commercial hip-hop eras to follow.

The core of Cornell’s collection came from author, curator, and former record executive Johan Kugelberg, who donated his collection in 1999 after publishing Born in the Bronx: A Visual History of the Early Days of Hip Hop with Joe Conzo, Jr. It has since expanded to 13 different collections from the archives of some of the culture’s earliest pioneers and documentarians. Hopefully many more of these will soon be digitized. But we might want to heed Jason Kottke’s warning in entering the three that have: “don’t click on any of those links if you’ve got pressing things to do.” You could easily get lost in this incredibly detailed treasury of hip-hop—and New York City—history.

Photo by Joe Conzo, Jr.

via Kottke

Related Content:

The “Amen Break”: The Most Famous 6‑Second Drum Loop & How It Spawned a Sampling Revolution

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness