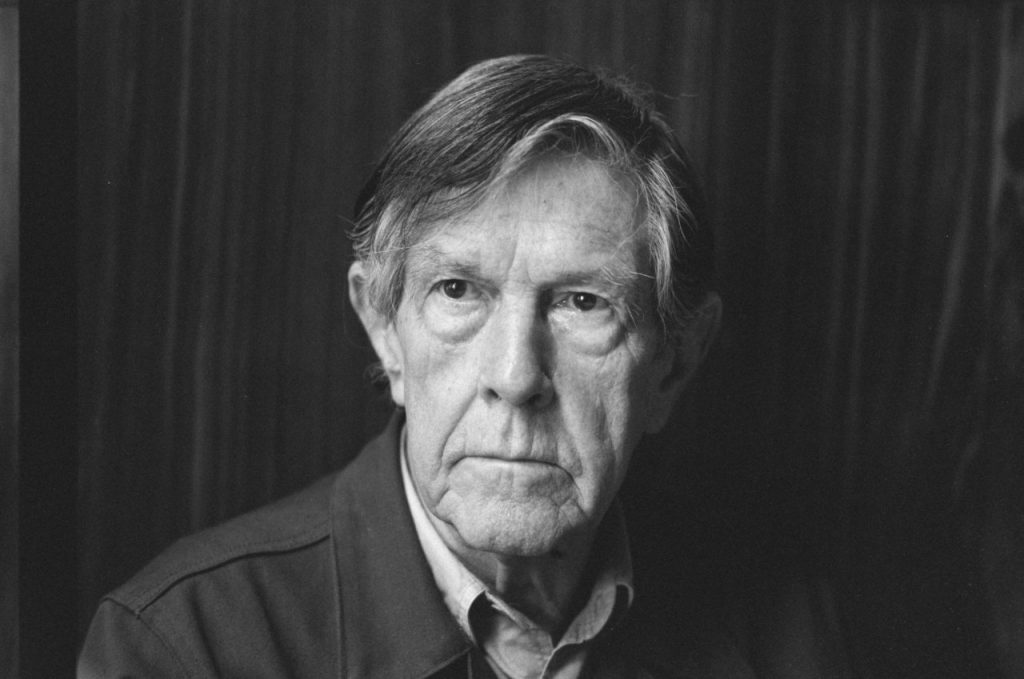

Few of us today, in search of unconventional artistry, would imagine mid-20th-century CBS game shows as a promising resource. But looking back, it turns out that American television of that era — a time and place when more people were exposed to the very same media than any before or since — managed to bring a surprising number of genuine creators before its mainstream-of-the-mainstream audience. In 1960, for instance, experimental composer John Cage performed Water Walk, his piece for a bathtub, pitcher, and ice cubes, on I’ve Got a Secret.

Three years later, Cage’s near-namesake John Cale took the show’s stage to play Erik Satie’s “melancholic yet deadpan, ecclesiastical yet demonic” Vexations. Though Cage didn’t make a reappearance for the occasion, he did have a connection to the music itself.

Dating to 1893 or 1894 and unpublished during Satie’s lifetime, Vexations’ score contains a note from the composer: “Pour se jouer 840 fois de suite ce motif, il sera bon de se préparer au préalable, et dans le plus grand silence, par des immobilités sérieuses,” taken by the piece’s interpreters to mean that they should play it 840 times in a row.

Or at least that’s how Cage and collaborator Lewis Lloyd interpreted it when they staged its first public performance in 1963 at the Pocket Theatre in Manhattan. Its rotating roster of players, under the banner of the Pocket Theatre Piano Relay Team, included a 21-year-old Cale. One week later on I’ve Got a Secret, the young Welshman’s participation in this daring performance constituted the secret the players had to guess. Having determined that his achievement has something to do with music, one lady asks the critical question: “Does it have anything to do with endurance?”

Yes, replies Cale, although the episode’s other secret-bearer, Karl Schenzer of the Living Theater, may have performed the real act of endurance as the sole audience member who stayed to watch the whole eighteen hours and forty minutes. (He certainly got a deal: Cage, believing that “the more art you consume, the less it should cost,” gave each audience member a five-cent refund for every twenty minutes they stayed.) I’ve Got a Secret’s home viewers then saw and heard Cale play Vexations, or at least 1/840th of it. They would hear from him again in his capacity as a founding member of the Velvet Underground — a band some of them would learn about a couple years later on the very same network’s Evening News with Walter Cronkite.

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. It’s a great way to see our new posts, all bundled in one email, each day.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

Related Content:

Nico, Lou Reed & John Cale Sing the Classic Velvet Underground Song ‘Femme Fatale’ (Paris, 1972)

Lou Reed, John Cale & Nico Reunite, Play Acoustic Velvet Underground Songs on French TV, 1972

Watch William S. Burroughs’ Ah Pook is Here as an Animated Film, with Music By John Cale

John Cage Performs Water Walk on US Game Show I’ve Got a Secret (1960)

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer, the video series The City in Cinema, the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future?, and the Los Angeles Review of Books’ Korea Blog. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.