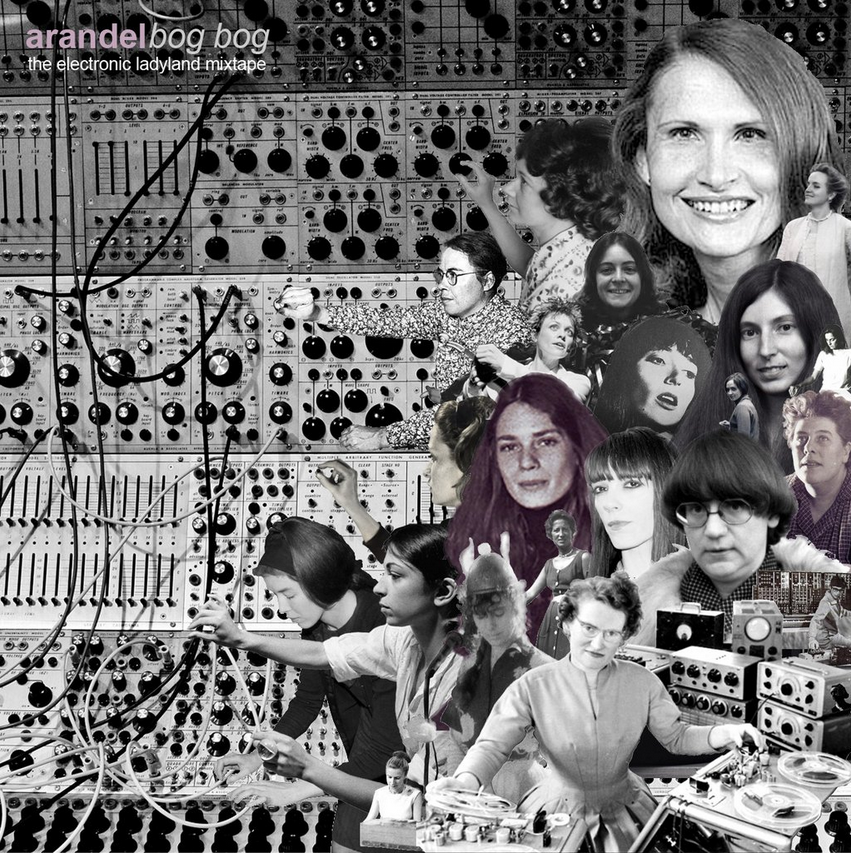

Given that we’ve previously featured two documentaries on electronic music pioneer Delia Derbyshire, an introduction to four other female composers who pioneered electronic music (Daphne Oram, Laurie Spiegel, Éliane Radigue & Pauline Oliveros), and seven hours of electronic music made by women between 1938 and 2014, no loyal Open Culture reader could claim ignorance on the theme of this new mixtape, Electronic Ladyland. It comes from the French musical project Arandel, whose members remain anonymous and could therefore be of any gender, but who, in these 45 minutes (made of 55 different tracks by 35 female composers), display a mastery of the field.

“We realized that an unconscious feminine electronic music Internationale has existed throughout the ages and we wondered whether a secret intuition might have gathered around shared research,” says Arandel in a translated interview. “Was their mutual desires achieved differently in different countries, with different tools in different timezones? The idea was to see what would happen if we gathered them in the same fictitious room for 45 minutes, and built a choir from all their productions.”

Arandel’s interviewer describes the musicians in the mix as coming from “very different musical horizons: we find academic learned musicians, research music composers and experimenters who used to do DIY works composed for advertising or television in a pop or easy listening context, some eccentric women like The Space Lady or Ruth White.” We also hear from famous names like Laurie Anderson and Wendy Carlos, and Delia Derbyshire. “What she accomplished is fascinating,” says Arandel of Derbyshire, “as is listening to her talk about her interesting work in documentaries,” and they’ve also included work from Daphne Oram, Laurie Spiegel, Eliane Radigue, and Pauline Oliveiros, subjects of the other documentaries we’ve posted here.

Electronic Ladyland drops you right into a retro-futuristic sonic landscape equally danceable and haunting, one with great variety as well as an unexpected consistency. It provides not just a kind of brief overview of what certain generations of female composers discovered with their new and then-strange electronic instruments and other devices, but one you may well want to keep in your library for frequent listening. It will also, according to Arandel, make you think: “There is an almost magic link between women and electronic music, from the 50’s / 60’s. Have you asked yourself the question of social, artistic, maybe magic reasons behind this link?” Hit the play button, and you may start. Find the list of tracks below.

1. Glynis Jones : Magic Bird Song (1976)

2. Doris Norton : Norton Rythm Soft (1986)

3. Colette Magny : « Avec » Poème (1966)

4. Daphne Oram : Just For You (Excerpt 1)

5. Laurie Spiegel : Clockworks (1974)

6. Pauline Oliveiros : Bog Bog (1966)

7. Megan Roberts — I Could Sit Here All Day (1977)

8. Suzanne Ciani : Paris 1971

9. Laurie Anderson : Tape Bow Trio (Say Yes) (1981)

10. Glynis Jones : Schlum Rooli (1975)

11. Ruth White : Mists And Rains (1969)

12. Wendy Carlos : Spring (1972)

13. Ann McMillan : Syrinx (1978)

14. Delia Derbyshire : Restless Relays (1969)

15. Maggi Payne : Flights Of Fancy (1986)

16. Else Marie Pade : Syv Cirkler (1958)

17. Daniela Casa : Ricerca Della Materia (1975)

18. The Space Lady : Domine, Libra Nos (1990)

19. Johanna Beyer : Music Of The Spheres [1938]

20. Maddalena Fagandini : Interval Signal (1960)

21. Eliane Radigue : Chryptus I (1970)

22. Ruth White : Owls (1969)

23. Ursula Bogner : Speichen (1979)

24. Beatriz Ferreyra — Demeures Aquatiques (1967)

25. Doris Norton : War Mania Analysis (1983)

26. Tera De Marez Oyens : Safed (1967)

27. Daphne Oram : Rhythmic Variation II (1962)

28. Mireille Chamass-Kyrou : Etude 1 (1960)

29. Laurie Spiegel : Drums (1983)

30. Teresa Rampazzi : Stomaco 2 (1972)

31. Teresa Rampazzi : Esofago 1 (1972)

32. Suzanne Ciani : Fourth Voice: Sound Of Wetness (1970)

33. Ursula Bogner : Expansion (1979)

34. Alice Shields : Sacrifice (1993)

35. Megan Roberts and Raymond Ghirardo : ATVO II (1987)

36. Laurie Anderson : Drums (1981)

37. Doris Hays : Somersault Beat (1971)

38. Lily Greenham : Tillid (1973)

39. Ruth Anderson : Points (1973–74)

40. Pril Smiley : Kolyosa (1970)

41. Catherine Christer Hennix : The Electric Harpsichord (1976)

42. Joan La Barbara : Solo for Voice 45 (from Songbooks) (1977)

43. Slava Tsukerman, Brenda Hutchinson & Clive Smith : Night Club 1 (1983)

44. Monique Rollin : Motet (Etude Vocale) (1952)

45. Sofia Gubaidulina : Vivente – Non Vivente (1970)

46. Ruth White : Spleen (1967)

47. Doris Hays : Scared Trip (1971)

48. Daphne Oram : Pulse Persephone (Alternate Parts For Mixing)

49. Maggi Payne : Gamelan (1984)

50. Laurie Spiegel : The Unquestioned Answer (1980)

51. Ursula Bogner : Homöostat (1985)

52. Wendy Carlos : Summer (1972)

53. Suzanne Ciani : Princess With Orange Feet

54. Pauline Oliveiros : Poem Of Change (1993)

55. Suzanne Ciani : Thirteenth Voice: And All Dreams Are Not For Sale (1970)

Related Content:

Hear Seven Hours of Women Making Electronic Music (1938- 2014)

Two Documentaries Introduce Delia Derbyshire, the Pioneer in Electronic Music

The History of Electronic Music in 476 Tracks (1937–2001)

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer, the video series The City in Cinema, the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future?, and the Los Angeles Review of Books’ Korea Blog. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.