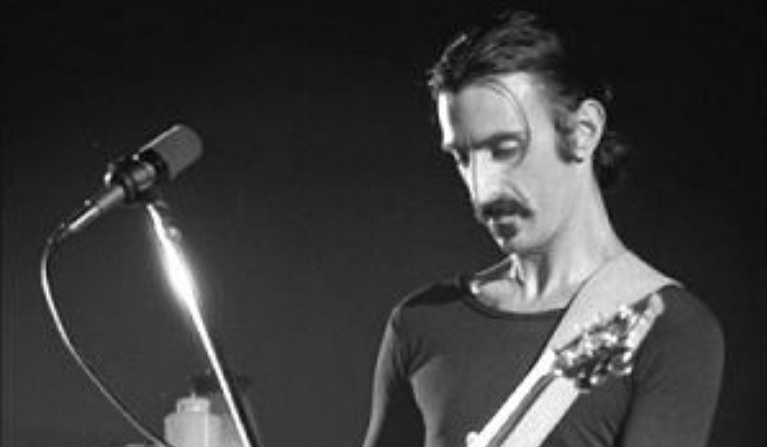

Rock stars who became respected actors… the pool is a small one, perhaps outnumbered by the many musicians who have made less successful attempts at movie stardom. But without a doubt, the former category includes David Bowie. In his various musical guises, Bowie the cracked actor put to use the skills he honed for decades on movie after movie. Not every film is worth watching, but nearly every performance contains seeds of greatness.

What you may not know is that Bowie the actor and Bowie the musician grew up together. He had always been both, taking his first film role in a short horror flick, The Image, back in 1967, the same year he released his first, self-titled album. You can be forgiven for never hearing about either. Neither one made much of an impression (and Bowie more or less disavowed the album). But the movie did have the rare distinction at the time of receiving an X rating. “I think it was the first short that got an X‑certificate,” says writer and director Michael Armstrong, “for its violence, which in itself was extraordinary.”

Tame by today’s standards, the movie features 20-year-old Bowie as a painting come to life. He got the part not because Armstrong—a fan of his first album—considered him “perfect for the role. It was really to give him a job.” Armstrong described his star to The Wall Street Journal as “very pretty” and “flirtatious” and remembers Bowie’s impressive Elvis impersonation. Bowie seems to have found the whole thing very funny. On set, there were “a lot of issues with corpsing—bursting into laughter during a take,” writes Metro.co.uk. When the film appeared in theaters, viewers expected to see porn—not only because of its X‑rating but also because, writes Rolling Stone, it “briefly screened between two porn films at a London theater.” (The film’s star saw the movie by himself in a theater filled with lone men in raincoats.) Bowie, says Armstrong, “thought it was hilarious.”

The Image has only recently appeared online thanks to the WSJ, who received permission from the David Bowie Archive to show it. You can watch the almost 14-minute film up top. (You can see a Youtube version below it.) Like Bowie’s first album, it may not herald the birth of a new star—his abilities as an actor may not have been fully evident until his first feature-length starring part in The Man Who Fell to Earth. But as with music, so with acting: Bowie never stopped working at the craft, and the films that fell flat seemed only to inspire him to work harder and create even more ambitious characters.

The Image will be added to our collection, 4,000+ Free Movies Online: Great Classics, Indies, Noir, Westerns, Documentaries & More.

via The Wall Street Journal/Metro

Related Content:

A 17-Year-Old David Bowie Defends “Long-Haired Men” in His First TV Interview (1964)

Hear Demo Recordings of David Bowie’s “Ziggy Stardust,” “Space Oddity” & “Changes”

How “Space Oddity” Launched David Bowie to Stardom: Watch the Original Music Video From 1969

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness