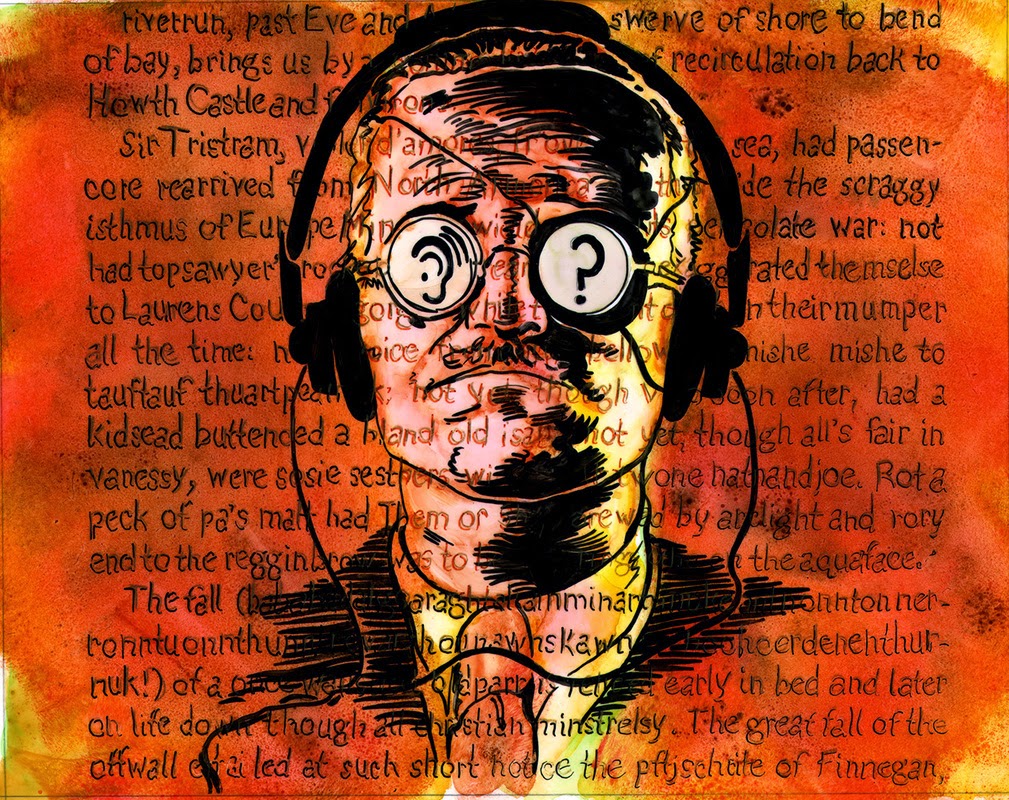

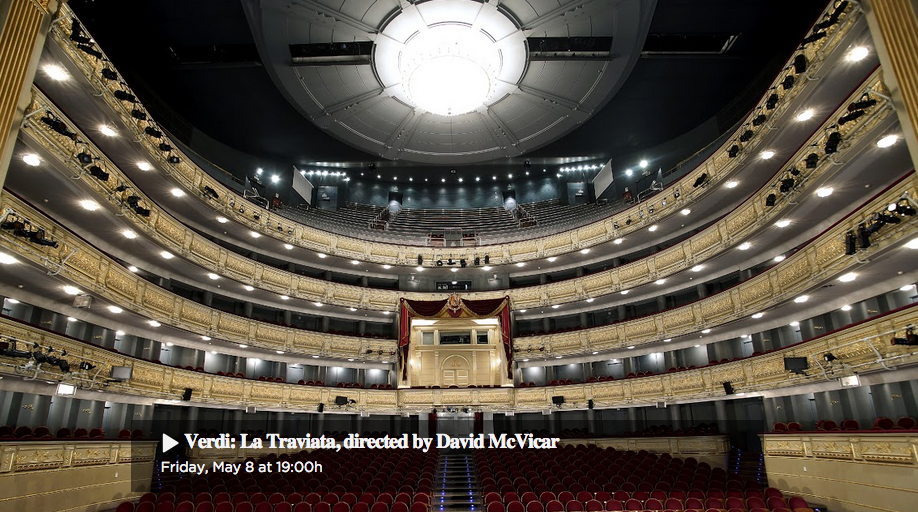

Click the image above to watch Verdi’s La Traviata.

Opera has always had its appreciators, and fervent ones at that, but in recent decades the form has had to extend its appeal beyond its inner circle of die-hard fans. Some of these efforts, such as the Metropolitan Opera’s high-definition broadcasts to movie theaters around the world, have proven surprisingly successful, encouraging the lowering of opera’s barrier to entry. Now, thanks to a site called The Opera Platform, you don’t have to go to a theater of any kind; you can watch full-length performances anywhere with an internet connection.

In order to promote itself as “the online destination for the promotion and enjoyment of opera” designed to “appeal equally to those who already love opera and to those who may be tempted to try it for the first time,” The Opera Platform offers one “showcase opera” per month, viewable free, in full, with subtitles available in six different languages. It also provides a host of supplementary materials, including documentary and historical materials that put the month’s featured opera in context.

“The Opera Platform is a partnership between Opera Europa, which represents opera companies and festivals; Arte, the Franco-German cultural broadcasting channel, and the participating opera companies,” writes the New York Times’ Michael Cooper. “It has a $4.5 million budget,” Reuters reported, “with about half coming from the European Union’s cultural budget.” So the site certainly has its resources in order, but what of its content?

The Opera Platform has come strong out of that particular gate with Verdi’s La Traviata, produced at Madrid’s Teatro Real, which you can watch for free until August 11. This tale of “the short and hectic life and tragic death of a high-society courtesan in 19th century Paris,” as the site’s notes put it, comes told through Verdi’s “music of profound humanity” and the staging of famed Scottish opera director David McVicar, “who, with his usual elegance, sets the drama in a world of romantic references while retaining an up-to-date perspective.”

Opera-lovers of previous generations could scarcely have imagined that technology would bring this degree of viewing convenience to their art form of choice. And now that The Opera Platform has got up and running, would-be opera-lovers have no excuse not to get into it, in the comfort of their own homes or anywhere else. And if you want to have some popcorn while you watch, go for it — nobody’s going to shake their opera glasses at you.

Related Content:

Ludwig Wittgenstein’s Tractatus Gets Adapted Into an Avant-Garde Comic Opera

Colin Marshall writes on cities, language, Asia, and men’s style. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer, and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.