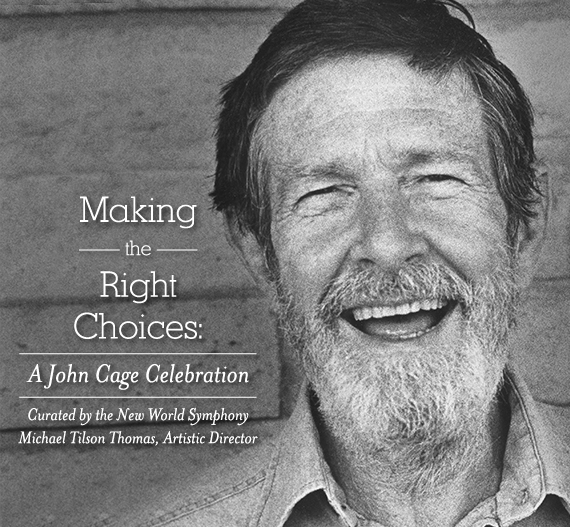

You don’t know avant-garde music unless you know John Cage. And now we have another rich, easily accessible online resource that can help us get to know John Cage better. The new site is called Making the Right Choices: A John Cage Celebration, and it has its origins in the celebration of Cage’s 100th birthday put on by conductor Michael Tilson Thomas and the New World Symphony in February 2013.

This Cage-devoted, Knight Foundation-funded site, in the words of Hyperallergic’s Allison Meier, “presents a comprehensive overview of his career, from a watering can poured on national television to a rhythmic solo piano performance inspired by lost love,” material from Cage’s life and career as well as material inspired by it, and of course “video and audio from the 2013 performances in Miami Beach, including some familiar and some obscure pieces from [Cage’s] influential and experimental career of both music and staged silence.”

You may remember when we featured Cage’s 1960 performance of Water Walk on I’ve Got a Secret. The site doesn’t fail to include that classic television clip, but it also offers videos on the staging of Water Walk today, from its direction and background to its rehearsal to the theatricality of its performance to the placement of the cameras filming it. You can find these and many other audiovisual explorations of the nuts and bolts of Cage’s work at Making the Right Choices’ catalog of videos.

“John Cage genuinely wanted to open up the beauteous experience of sound for everyone,” writes Tilson Thomas in a piece on the composer. “Much of his work could be described as kits to be used in the creation of a performance that relies on the perceptions, imaginations and choices of the musicians. It was a spiritual mission for him to create the opportunity for the performance to exist while at the same time to interfere with it as little or as subtly as possible.” That challenge Cage set for himself keeps his work fascinating to us to this day — and as Tilson Thomas and the New World Symphony surely found out, it remains as much of a challenge as ever for those who pick it up today.

Visit Making the Right Choices: A John Cage Celebration .

via Hyperallergic

Related Content:

John Cage Performs Water Walk on US Game Show I’ve Got a Secret (1960)

10 Rules for Students and Teachers Popularized by John Cage

Hear Joey Ramone Sing a Piece by John Cage Adapted from James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake

Watch a Surprisingly Moving Performance of John Cage’s 1948 “Suite for Toy Piano”

Colin Marshall writes on cities, language, Asia, and men’s style. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer, and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.