When This is Spinal Tap came out over 30 years ago, it went over a lot of people’s heads. “Everybody thought it was a real band,” recalled director Rob Reiner. “Everyone said, ‘Why would you make a movie about a band that no one has heard of?’”

It’s hard to believe that lines like “You can’t dust for vomit” failed to come off as anything but a joke. But, to be fair, Hollywood comedies were generally straight-forward affairs in the ‘80s. Think Blues Brothers or Fletch. Fake documentaries weren’t a thing. And This is Spinal Tap looks and feels exactly like a rock documentary– the hagiographic voiceover, the shaky camera, the awkward interviews.

The movie was just as unscripted as rock docs like Don’t Look Back, The Song Remains the Same and The Kids Are All Right. The film is not only a parody of the generally overblown silliness of rock and roll, it is also, as Newsweek’s David Ansen notes, “a satire of the documentary form itself, complete with perfectly faded clips from old TV shows of the band in its mod and flower-child incarnations.”

And then there’s the fact that, for a fake band, Spinal Tap knew how to rock — albeit to completely idiotic lyrics. Christopher Guest, Michael McKean and Harry Shearer, the actors who make up the core of the band, actually played all the music in the movie. And after the cult success of the film, they went on to play concerts. Can you really call Spinal Tap a fake band if they wowed audiences in Wembley Stadium?

But the genius stroke of the movie was to mix in pain and dread with the humor. As we’re laughing at David St. Hubbins and company fretting over an 18-inch Stonehenge prop, we also wince in sympathy. Sting reportedly told Rob Reiner that he watches the movie every time he is about to go on tour. “Every time I watch it, I don’t know whether I should laugh or cry.”

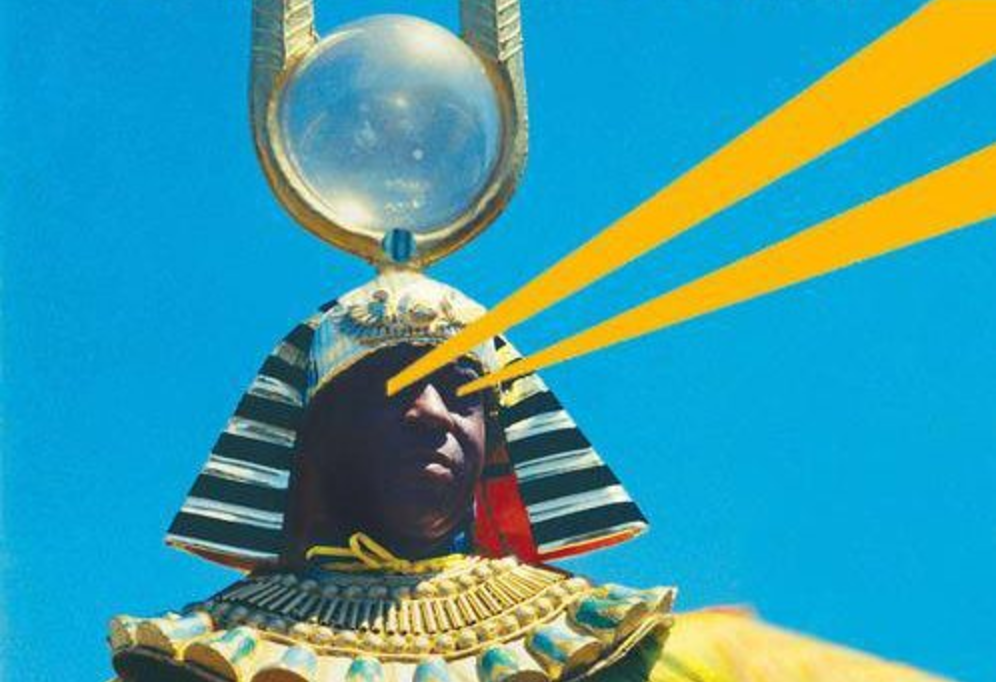

Spinal Tap made its first appearance in 1979, five years before the movie premiered. It was on a short-lived ABC SCTV-like comedy series called The T.V. Show that starred Reiner. You can see Guest, McKean and Shearer and company rocking out to the tune “Rock n Roll Nightmare” right above. Though the performance is not nearly as tight or funny as their subsequent appearances, all of the ideas are there. The bloated pretentiousness. The silly lyrics. The sillier outfits. By the way, that bottle-wielding keyboardist in the clip is Loudon Wainwright III.

A couple years later, Reiner and company decided to revisit Spinal Tap with the idea of making a mockumentary. As Reiner recounted in an interview with Sound Opinions:

They gave us the money and we realized that there was no way in screenplay form that we could capture what this would be. Because it was going to be a documentary. So I said to the guy, give us the money you were going to give us to write the screenplay and I’ll make you a little bit of the film. And we made like 20 minutes of this film. We had backstage footage. We had concert footage. Interview stuff.

You can watch the whole demo film (Spinal Tap: The Final Tour) up top in two parts. The hair might be different and some of the gags might not land with the same punch, but the chemistry, the concept and the comedy are all there. In fact, some clips from the demo, particularly the interviews, made their way into the final cut of the movie.

Sadly, the demo failed to impress the production company. “The guy [at the production company] said, ‘I don’t like this.’ So we went around for years to get it made. And finally, we were able to put it together for a couple of million bucks.”

You can watch Reiner recount the making and legacy of This is Spinal Tap below. Spinal Tap: The Final Tour will be added to our collection, 4,000+ Free Movies Online: Great Classics, Indies, Noir, Westerns, Documentaries & More.

Related Content:

Ian Rubbish (aka Fred Armisen) Interviews the Clash in Spinal Tap-Inspired Mockumentary

Spinal Tap’s Nigel Tufnel Promotes World’s Largest Online Guitar Lesson

Jonathan Crow is a Los Angeles-based writer and filmmaker whose work has appeared in Yahoo!, The Hollywood Reporter, and other publications. You can follow him at @jonccrow. And check out his blog Veeptopus, featuring lots of pictures of badgers and even more pictures of vice presidents with octopuses on their heads. The Veeptopus store is here.