Rock critic and scholar Greil Marcus has just released a book with Yale Press called The History of Rock ‘n’ Roll in Ten Songs, and it appears to be an unusual take on a very hackneyed subject, as Marcus admits in the video trailer above: “Everybody knows the history of rock ‘n’ roll,” he says, “What if it was just about a few songs?” “Unlike all previous versions of rock ‘n’ roll,” writes Yale, “this book omits almost every iconic performer and ignores the storied events and turning points that everyone knows.” This is not entirely true—you’ve got your Beatles, you’ve got your Buddy Holly, but you’ve also got… Joy Division. And a number of other surprising, offbeat choices that don’t necessarily sound like rock ‘n’ roll history, but certainly tell it their various ways. “At any given moment,” Marcus says above, any of these songs “could contain the whole history […] the whole DNA of rock ‘n’ roll.”

Some of the choices seem like personal quirks. Nothing to get too bent out of shape about, if that’s your tendency, but odd nonetheless. The Flaming Groovies would not be a band I’d choose as representative of garage rock, if that’s what they represent. Their song “Shake Some Action” above may be better known for some from Cracker’s workmanlike cover on the Clueless soundtrack than as a genuine hit in its own right. But the single sure had a cool cover.

It also has some excellent guitar work and a perfectly distinctive tone that Marcus can’t forget. Its lyrics are by turns vapid and creepy, which, now that I think of it, perhaps makes this a perfect track to define much of rock ‘n’ roll history.

No one bested post-punk darlings Joy Division when it came to boyish good looks and relentless despair. In an oblique rock history sense, they were pivotal, taking the obscurantist minimalist experiments of bands like Wire and making them viable options for an entire genre of music. Marcus chooses “Transmission” instead of the much more popular “Love Will Tear Us Apart,” which has become almost a musical rite of passage for certain bands to cover. This was the last single the band released before singer Ian Curtis killed himself. “It’s sort of fitting then,” writes Consequence of Sound, “that this would be both one of the band’s most popular songs and also pave the way for New Order, specifically in terms of its sound and direction.” Little live footage of the band exists. See them above in 1979 on UK retro television program The Wedge (originally broadcast on Something Else with the Jam).

Marcus’ third choice is not really what we think of as rock and roll, but it’s a close cousin, and without doo wop, we’d have had no Lou Reed. 1956’s “In the Still of the Night,” written by Fred Parris and recorded by his Five Satins in a Catholic school basement, was a hit in the 90s for Boyz II Men on the R&B and Adult Contemporary charts and reliably appears in films about the fifties. Marcus also refers to a version recorded by the Slades, a white vocal group. The pairing illustrates the familiar fifties practice of white groups recording black artists—and often outselling them, though certainly not in this case—for presumably segregated audiences.

Etta James’ 1960 soaring lament “All I Could Do Was Cry” again seems a world away from rock and roll, with its lush studio string section and spacious, spare production. The song lacks the bite and growl of “At Last!” from the same album, but Marcus makes a weighty allusion in referring to two different versions. By including Beyoncé’s take on the song, the list hauls in the history of Chicago’s Chess records and Knowles’ outstanding performance as James in 2008’s Cadillac Records, a film that takes us from Muddy Waters’s electric blues to Chuck Berry’s hybrid crossover sound.

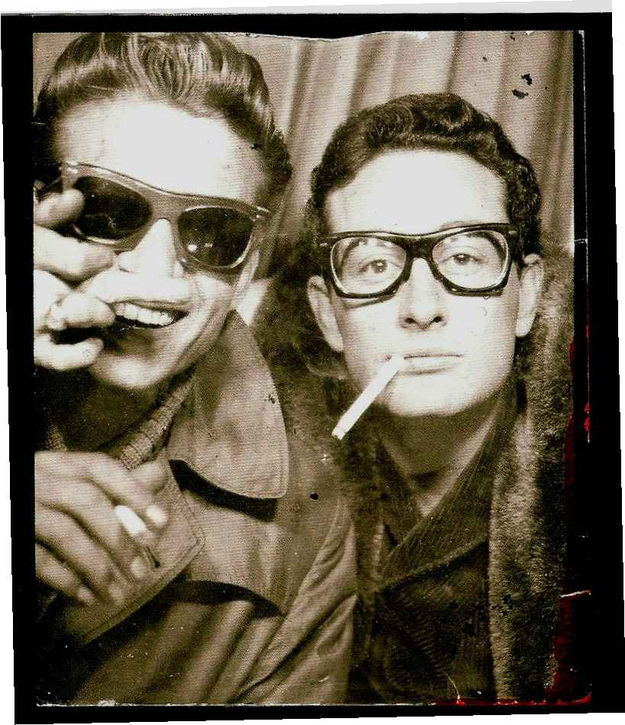

Yes, we have Buddy Holly, but we don’t have “Peggy Sue” or “Not Fade Away.” Instead Marcus gives us the B‑side to the posthumously released “Peggy Sue Got Married,” a song called “Crying, Waiting, Hoping.” Originally recorded by Holly alone in a Manhattan apartment and mixed with studio backing tracks by producer Jack Hansen in 1959, the song had nothing to do with Holly’s fame in life—hence the bad vocal sync in the video above. The band’s playing an entirely different song. Marcus chose this as symbolic of the Holly mythos after his death, which spread across the ocean to Merseybeat bands like the Beatles, who often covered this song and recorded it live on the BBC. Like the musicians who played on the first record, they aren’t just covering Holly, writes Marcus, “they’re conducting a kind of séance with him.”

Speaking of the Beatles: everyone knows their “Money (That’s What I Want),” but did you know that the song, performed in 1959 by Barrett Strong (above), was the first hit for Berry Gordy’s Motown records (then Tamla)? A direct link between American R&B and the UK variety, “Money” was a staple for British invasion bands in the early 60s.

I had never heard of The Brains before reading Marcus’ list. That’s not saying a whole lot, but I had also never heard Cyndi Lauper’s 1983 hit cover of their minor hit “Money Changes Everything,” or even the rare Smiths’ instrumental version, ardent fan though I am. So chalk that up to a musical blind spot, if you will, or take it as evidence of the song’s outlier status. Hear the 1978 original above. Marcus has said elsewhere of its raw, cynical honesty that “there’s no other way the decade could end.”

“This Magic Moment,” the 1960 hit by Ben E. King and the Drifters, sounds like the perfect choice of song for nostalgic boomers, not so much for jaded rock writers telling a new story of rock ‘n’ roll, but there you have it. Marcus also refers to a version by “Ben E. King with Lou Reed.” As far as I can tell, no such recording exists, but we do have a version by Reed alone. Hear it above.

The only way perhaps to discuss this ninth “song” in any rock ‘n’ roll context is by way of Lou Reed, it so happens. Reed’s “thoroughly alienating” Metal Machine Music consists of 64 minutes of feedback and distortion caused, some legends have it, by Reed recording the sound of his guitar leaning against a cranked-up amp. Artist Christian Marclay does him one better. “Guitar Drag” is exactly what it advertises, the sound—and video, above—of a guitar dragged behind a truck. Representing the pure noise of Metal Machine Music and the general destructiveness of rock ‘n’ roll, it also re-enacts the absolutely horrifying 1998 dragging death of James Byrd, Jr, one of the lowest moments in American racial history. Does this disturbing piece of sound/video art aestheticizing a racist murder, chilling and gruesome beyond words, belong on any list about rock ’n’ roll history? Greil Marcus thinks it does.

We return to familiar, if cloying territory with “To Know Is to Love Him,” an early hit for Phil Spector and his Teddy Bears in 1958 (above)—written not about a crush but about Spector’s deceased father after the words on his headstone. Next to the quaintness of this recording, Marcus also lists Amy Winehouse’s 2007 cover (below). Maybe he hears them at once, both songs haunting each other. Writing on the song in The Guardian after Winehouse’s death, Marcus says “it took 48 years to find its voice.” It’s a story of two incredibly talented, and tragically disturbed, rock ‘n’ roll characters, and one of the pain and loss that lie behind even the most bubblegum of hits. See Yale Press’s website for more on Marcus’ The History of Rock ‘n’ Roll in Ten Songs.

Related Content:

A History of Rock ‘n’ Roll in 100 Riffs

100 Years of Rock in Less Than a Minute: From Gospel to Grunge

Revisit The Life & Music of Sister Rosetta Tharpe: ‘The Godmother of Rock and Roll’

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness