Some people think Chuck Berry invented rock and roll. Chuck Berry sure thinks so. But I say it was Bo Diddley. At least Diddley invented the rock and roll I love—throbbing, dirty, hypnotic, hovering in some space between the blues, gospel and African rhythms but also with its feet firmly planted on any industrial city streetcorner. Bo Diddley invented irony in rock (his first band was called “The Hipsters”). Bo Diddley never pandered to the teenybopper crowd (though he did go commercial in the 80s). Even his biggest hits have about them an otherworldly air of echo‑y weirdness, with their signature beat and one-note drone. Also something vaguely sleazy and maybe a little sinister, essential elements of rock and roll worthy of the name.

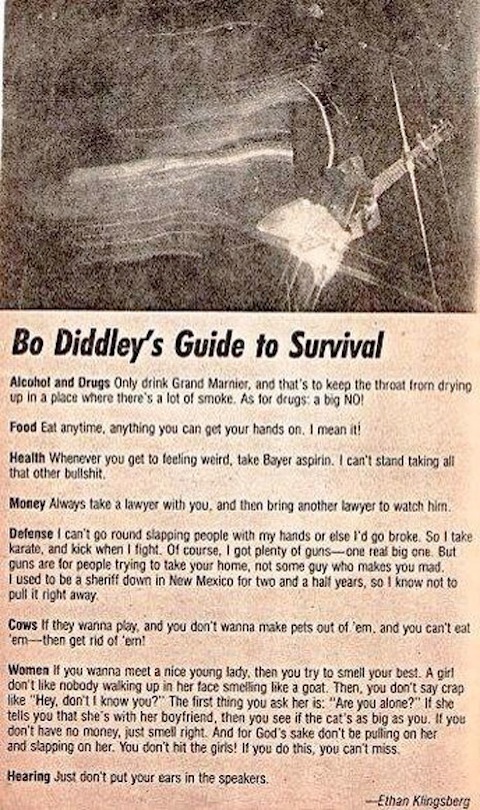

So, as a man who made his own rhythm, his own tones, his own studio, and his own guitar—who was so much his own man that one of his best known songs is named after him—it stands to reason that he would also make his own set of rules for surviving the music business. Called “Bo Diddley’s Guide to Survival,” the list covers all the bases: drugs and booze (“NO!”), food (“anything you can get your hands on”), health, money, defense, cows, women, and hearing. What more is there, really?

The list, clearly part of a magazine feature, has circulated on the internet for some time, but no one has managed to track down the source. It’s probably genuine, though; it sounds like the perfect mix of the down-to-earth and far-out funny that was Bo Diddley. I’m particularly intrigued by his very specific defense techniques (Elvis obviously took notes). It is true, by the way, that Diddley once served as a sheriff in New Mexico, a fact that adds so much to the mystique. Where “Defense” and “Women” get lengthy (and respectful) treatments, his succinct take on “Hearing” is as practical as it gets.

See the original list at the top and read the full transcript below. As you do, listen to the timeless weirdness of “Bo Diddley” above. There’s nothing else like it.

Alcohol and Drugs Only drink Grand Marnier, and that’s to keep the throat from drying up in a place where there’s a lot of smoke. As for drugs: a big NO!

Food Eat anytime, anything you can get your hands on. I mean it!

Health Whenever you get to feeling weird, take Bayer aspirin. I can’t stand taking all that other bullshit.

Money Always take a lawyer with you, and then bring another lawyer to watch him.

Defense I can’t go around slapping people with my hands or else I’d go broke. So I take karate, and kick when I fight. Of course, I got plenty of guns — one real big one. But guns are for people trying to take your home, not some guy who makes you mad. I used to be a sheriff down in New Mexico for two and a half years, so I know not to pull it right away.

Cows If they wanna play, and you don’t wanna make pets out of ‘em, and you can’t eat ‘em — then get rid of ‘em!

Women If you wanna meet a nice young lady, then you try to smell your best. A girl don’t like nobody walking up in her face smelling like a goat. Then, you don’t say crap like “Hey, don’t I know you?” The first thing you ask her is: “Are you alone?” If she tells you that she’s with her boyfriend, then you see if the cat’s as big as you. If you don’t have no money, just smell right. And for God’s sake don’t be pulling on her and slapping on her. You don’t hit the girls! If you do this, you can’t miss.

Hearing Just don’t put your ears in the speakers.

Related Content:

Chuck Berry Takes Keith Richards to School, Shows Him How to Rock (1987)

Keith Richards Waxes Philosophical, Plays Live with His Idol, the Great Muddy Waters

A History of Rock ‘n’ Roll in 100 Riffs

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness