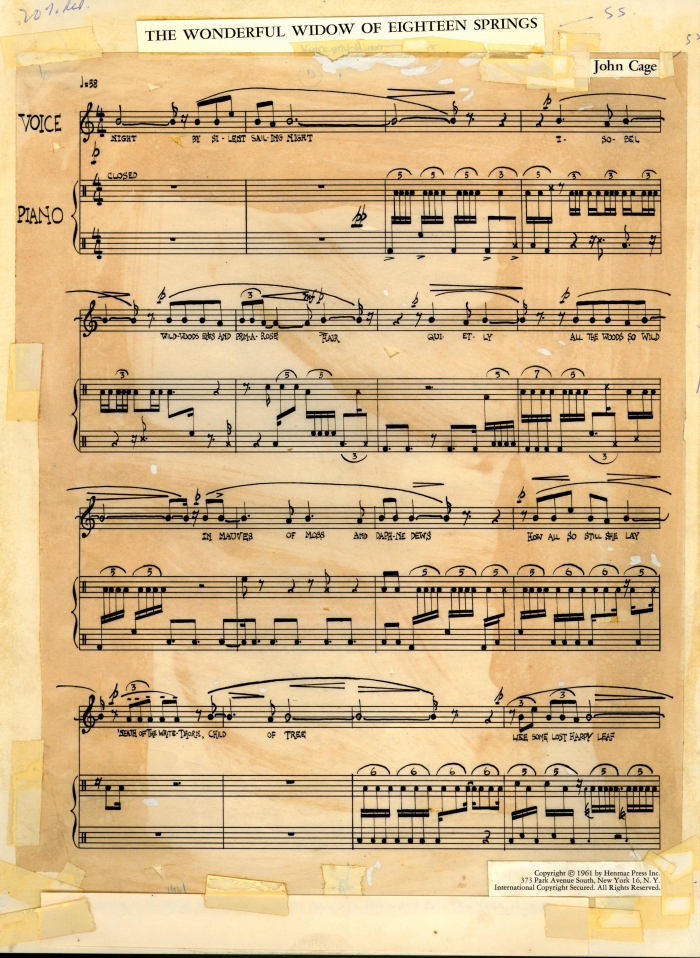

Once you hear Erik Satie’s Gymnopédie No. 1, you never forget it. Not that popular culture would let you forget it: the piece has been, and continues to be, reinterpreted and sampled by musicians working in a variety of genres from pop to electronic to metal. In versions that sound close to what Satie would have intended when he composed it in 1888, it’s also been featured in countless films and television shows. It’s even heard with some frequency in YouTube videos, though in the case of the one from The Music Professor above, it’s not just the soundtrack, but also the subject. Using an annotated score, it explains just what makes the piece so enduring and influential.

Upon “a simple iambic rhythm with two ambiguous major 7th chords,” Gymnopédie No. 1 introduces a melody that “floats above an austere procession of notes,” then “moves down the octave from F# to F#.” With its lack of a clear key, as well as its lack of development and drama that the orchestral music of the day would have trained listeners to expect, the piece was “as shocking as the dance of naked Spartans it was meant to evoke.”

The melody makes its turns, but never quite arrives at its seeming destinations, going around in circles instead — before, all of a sudden, swerving into the “minor and dissonant” before ending in “profound melancholy.”

Despite music in general having long since assimilated the daring qualities of Gymnopédie No. 1, the original piece still catches our ears — in its subtle way — whenever it comes on. So, in another way, do the less recognizable and more experimental Gnossiennes with which Satie followed them up. In the video above, the Music Professor provides a visual explanation of Gnossienne No. 1, during whose performance “soft dissonance hangs in the air” while “a curious melody floats over gentle syncopations in the left hand” over just two chords. The score comes with “surreal comments”: “Très luisant,” “Du bout de la pensée,” “Postulez en vous-même,” “Questionez.” Satie is often credited with pioneering what would become ambient music; could these be proto-Oblique Strategies?

Related Content:

Listen to Never-Before-Heard Works by Erik Satie, Performed 100 Years After His Death

The Velvet Underground’s John Cale Plays Erik Satie’s Vexations on I’ve Got a Secret (1963)

How Erik Satie’s “Furniture Music” Was Designed to Be Ignored and Paved the Way for Ambient Music

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall.