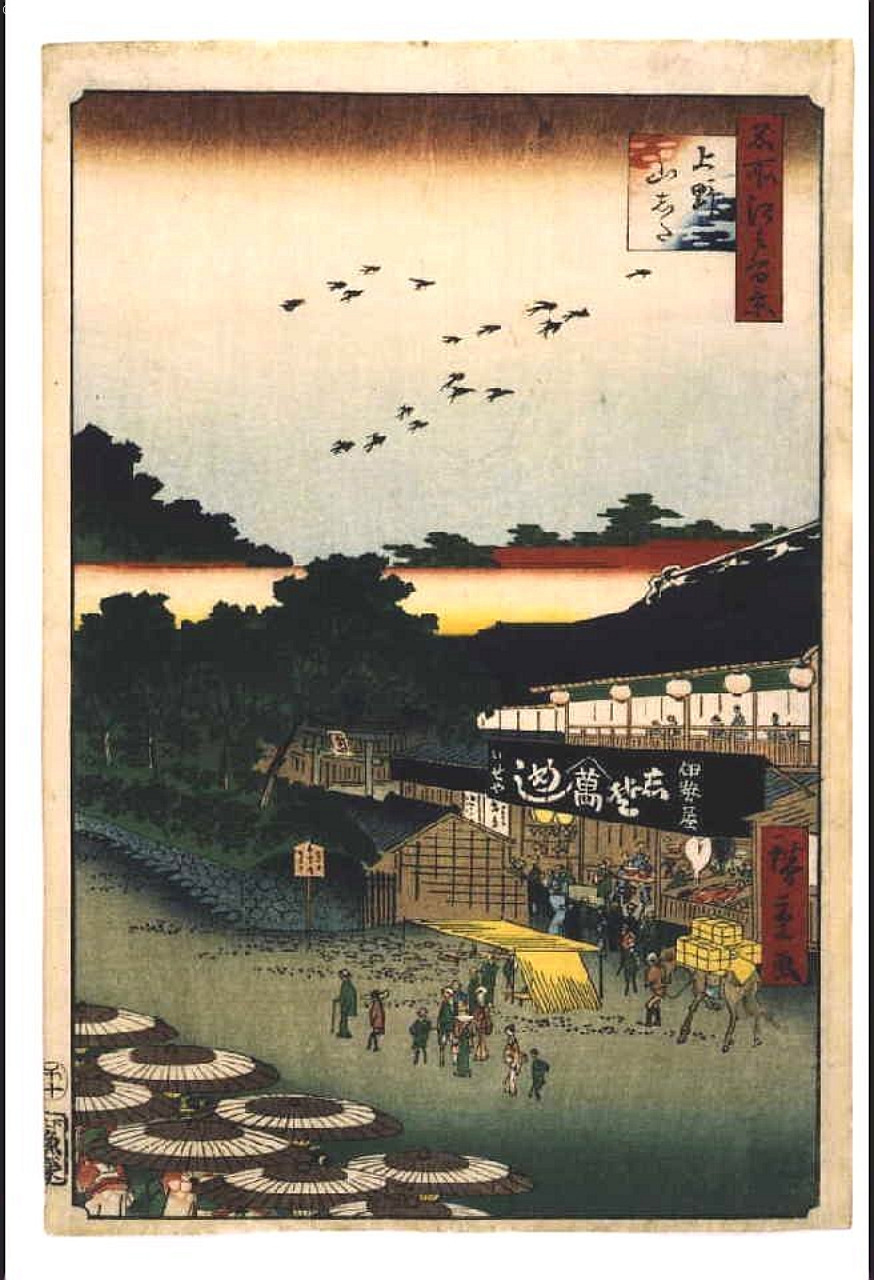

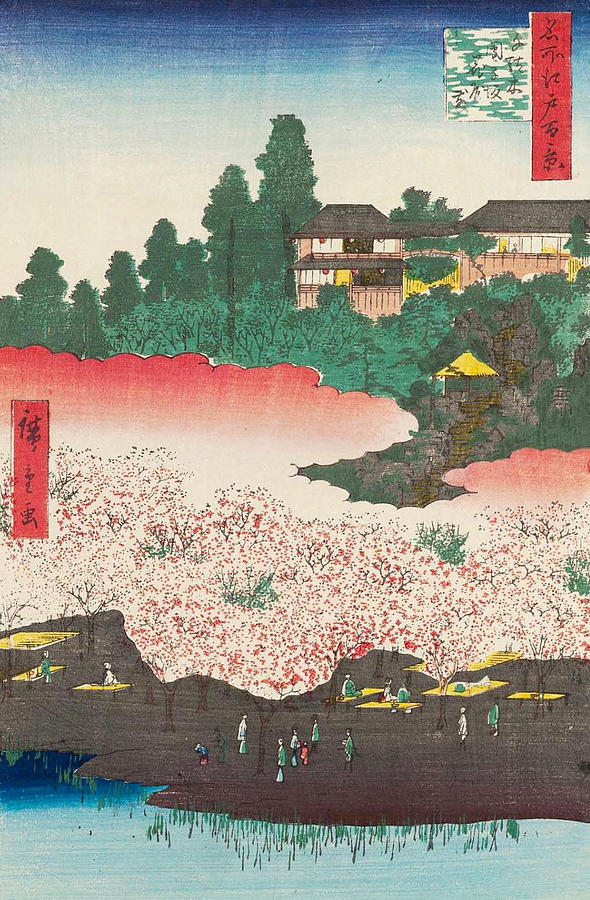

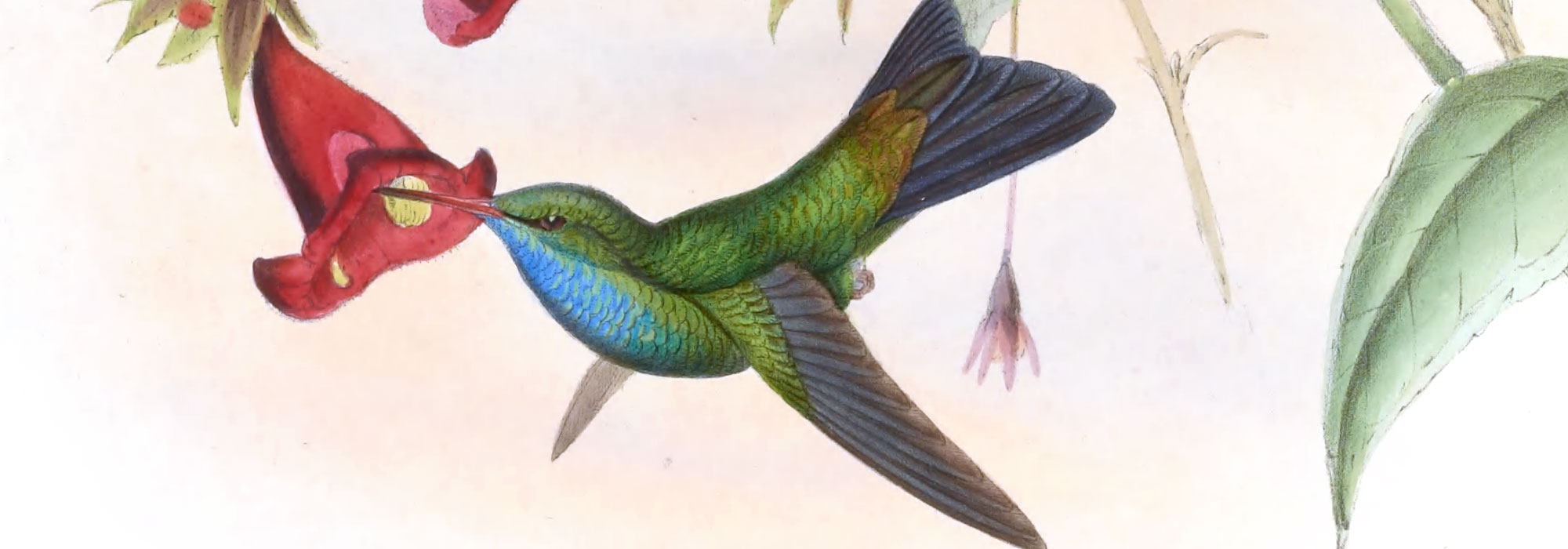

If you don’t live in a part of the world with a lot of hummingbirds, it’s easy to regard them as not quite of this earth. With their wide array of shimmering colors and frenetic yet eerily stable manner of flight, they can seem like quasi-fantastical creatures even to those who encounter them in reality. They certainly captured the imagination of English ornithologist John Gould, who between the years of 1849 and 1887 created A Monograph of the Trochilidæ, or Family of Humming-Birds, a catalog of all known species of hummingbird at the time. As you might expect, this is just the kind of old book you can peruse at the Internet Archive, but now there’s also an online restoration that returns Gould’s illustrations to their original glory.

A Monograph of the Trochilidæ “is considered one of the finest examples of ornithological illustration ever produced, as well as a scientific masterpiece,” writes the site’s creator, Nicholas Rougeux (previously featured here on Open Culture for his digital restorations of British & Exotic Mineralogy and Euclid’s Elements).

“Gould’s passion for hummingbirds led him to travel to various parts of the world, such as North America, Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru, to observe and collect specimens. He also received many specimens from other naturalists and collectors.” Taken together, the work’s five volumes — one of them published as a supplement years after his death — catalog 537 species, documenting their appearance with 418 hand-colored lithographic plates.

All these images were “analyzed and restored to their original vibrant colors in a process that took nearly 150 hours to complete. As much of the original plate was preserved — including the delicate colors of the scenic backgrounds in each vignette.” You can view and download them at the site’s illustrations page, where they come accompanied by Gould’s own text and classified according to the same scheme he originally used. You may not know your Phaëthornis from your Sphenoproctus, to say nothing of your Cyanomyia from your Smaragdochrysis, but after seeing these small wonders of the natural world as Gould did (all arranged into a chromatic spectrum by Rougeux to make a striking poster), you may well find yourself inspired to learn the differences — or at least to put a feeder outside your window.

via Kottke

Related content:

The Hummingbird Whisperer: Meet the UCLA Scientist Who Has Befriended 200 Hummingbirds

What Kind of Bird Is That?: A Free App From Cornell Will Give You the Answer

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.