What is any major American city if not an industrial gallery bustling with people and machines? Sometimes the images are bleak, as with the photo essays that often circulate of Detroit’s beautiful ruin; sometimes they are defiantly hopeful, as with those of the rising of New Orleans; and sometimes they are almost unfathomably monumental, as with the images here of New York City, circa the 20th century—or a great good bit of it, anyway.

You can survey almost a hundred years of New York’s indomitable grandeur by perusing over 900,000 images from the New York City Municipal Archives Online Gallery.

Photos like the astonishing tableaux in a sunlight-flooded Grand Central Terminal at the top (taken sometime between 1935 and 41) and like the breathtaking scale on display in the 1910 exposure of the Queensboro Bridge, above.

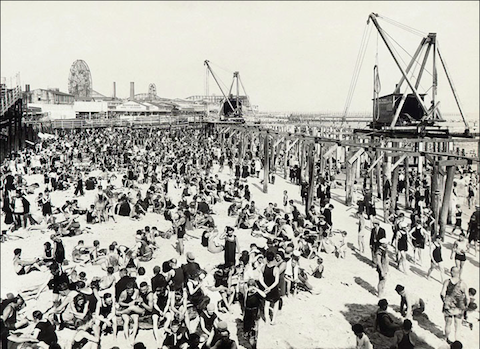

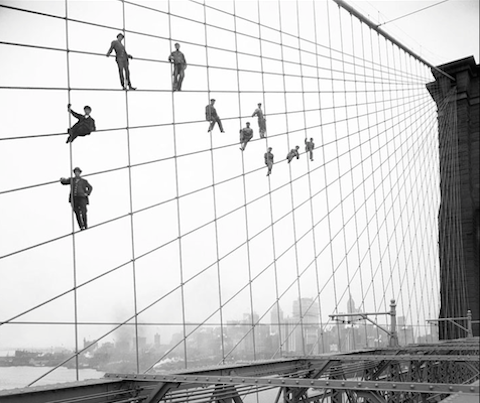

The online gallery features large-format photos of the human, like the sea of bathers above; of the human-made, like the vaulted, cavernous City Hall subway station below; and of the melding of the two, like the painters posing on the cables of the Brooklyn Bridge, further down.

These images come from a selection of photos culled from the various galleries by The Atlantic. For more, see the NYC Municipal Archives site, which you can search by keyword or other criteria. “Visitors,” writes the site, “are encouraged to return frequently as new content will be added on a regular basis. Patrons may order reproductions in the form of prints or digital files.”

Many of the images have watermarks on them to prevent illegal use. Nonetheless the gallery is a jaw-dropping collection of photos you can easily get lost in for hours, as well as an important resource for historians and scholars of 20th century American urbanism. See The Atlantic’s selection of images for even more dazzling photos. Or better yet, start rummaging through the New York City Municipal Archives Online Gallery right here.

Related Content:

New York Public Library Puts 20,000 Hi-Res Maps Online & Makes Them Free to Download and Use

Great New Archive Lets You Hear the Sounds of New York City During the Roaring 20s

Vintage Video: A New York City Subway Train Travels From 14th St. to 42nd Street (1905)

Designer Massimo Vignelli Revisits and Defends His Iconic 1972 New York City Subway Map

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness