You may not be interested in politics, they say, but politics is interested in you. The same, if you believe famed mythologist Joseph Campbell, goes for myth: far from explaining only the origin of the world as believed by extinct societies, it can explain the power of stories we enjoy today — up to and including Star Wars.

The man behind PBS’ well-known series The Power of Myth left behind many words in many formats telling us precisely why, and now you can hear a fair few of them — 48 hours worth — for free on this Spotify playlist. (If you don’t have Spotify’s software already, you can download it free here.)

“From the Star Wars trilogy to the Grateful Dead,” says the Joseph Campbell Foundation, “Joseph Campbell has had a profound impact on our culture, our beliefs, and the way we view ourselves and the world.” This collection, The Lectures of Joseph Campbell, which comes from early in his career, offers “a glimpse into one of the great minds of our time, drawing together his most wide-ranging and insightful talks” in the role of both “a scholar and a master storyteller.” So not only can Campbell enrich our understanding of all the stories we love, he can spin his lifetime of mythological research into teachings that, in the telling, weave into a pretty gripping yarn in and of themselves.

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. It’s a great way to see our new posts, all bundled in one email, each day.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

Related Content:

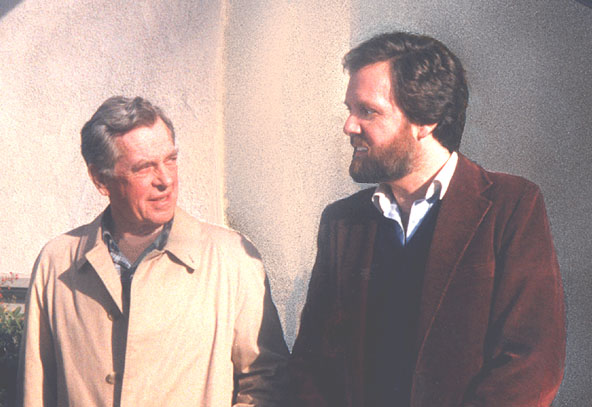

Joseph Campbell and Bill Moyers Break Down Star Wars as an Epic, Universal Myth

The Zen Teachings of Alan Watts: A Free Audio Archive of His Enlightening Lectures

How Star Wars Borrowed From Akira Kurosawa’s Great Samurai Films

Everything I Know: 42 Hours of Buckminster Fuller’s Visionary Lectures Free Online (1975)

Colin Marshall writes on cities, language, Asia, and men’s style. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer, and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.