George Orwell and Winston Churchill didn’t agree on much. For example, while Orwell wrote with deep sympathy about coal miners in The Road to Wigan Pier, Churchill, as home secretary, brutally crushed a miner’s strike in Wales. Orwell’s early years as “an apparatchik in the last days of the empire… left him with a hatred of authority and imperialism,” writes Richard Eilers. Churchill was a committed imperialist all his life, instrumental in prolonging a famine in British India that killed “at least three million people.”

Importantly for history’s sake, they agreed on the need to confront, rather than appease, the Nazis, against both the British left and right of the 1930s. “At a time not unlike today,” says journalist Tom Ricks, “when people were wondering whether democracy was sustainable, when a lot of people thought you needed authoritarian rule, either from the right or the left, Orwell and Churchill, from their very different perspectives, come together on a key point. We don’t have to have authoritarian government.”

Maybe somewhat less important—but strenuously agreed upon nonetheless by these two figures—was the need for clear, concise prose that avoids obfuscation. In Politics and the English Language—an essay routinely taught in college composition classes—Orwell describes politically misleading writing as overstuffed with “pretentious diction” and “meaningless words.” These are, he writes, signs of a “decadent… civilization.” Churchill has had at least as much influence as Orwell on a certain kind of political writing, though not the kind most of us read often.

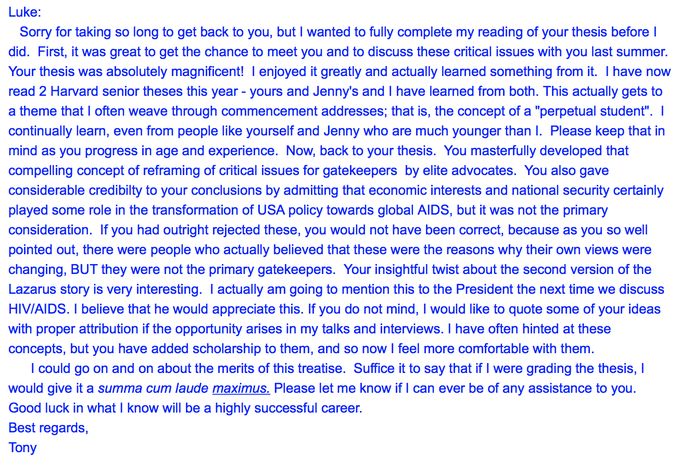

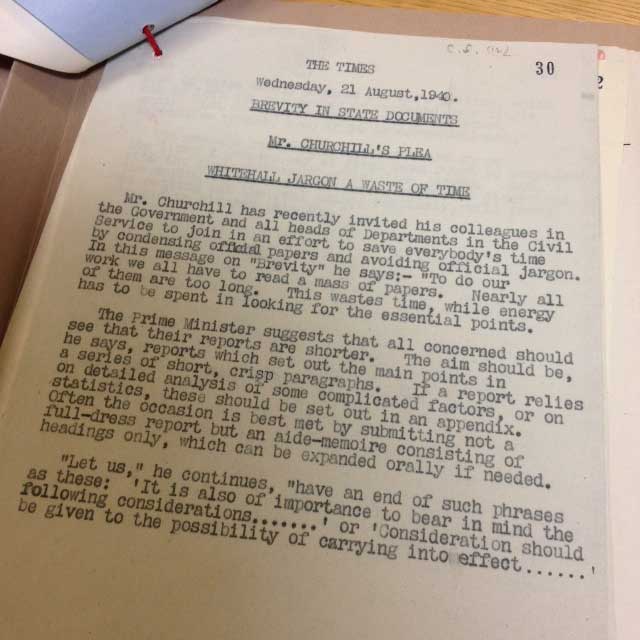

In 1940, Churchill issued a memo to his staff titled “Brevity.” He did not express concerns about creeping fascism in bureaucratic communiques, but decried the problem of wasted time, “while energy has to be spent in looking for the essential points.” He ends up, however, saying some of the same things as Orwell, in fewer words.

I ask my colleagues and their staffs to see to it that their Reports are shorter.

- The aim should be Reports which set out the main points in a series of short, crisp paragraphs.

- If a Report relies on detailed analysis of some complicated factors, or on statistics, these should be set out in an Appendix.

- Often the occasion is best met by submitting not a full-dress Report, but an Aide-memoire consisting of headings only, which can be expanded orally if needed.

- Let us have an end of such phrases as these: “It is also of importance to bear in mind the following considerations…,” or “Consideration should be given to the possibility of carrying into effect….” Most of these woolly phrases are mere padding, which can be left out altogether, or replaced by a single word. Let us not shrink from using the short expressive phrase, even if it is conversational.

Reports drawn up on the lines I propose may at first seem rough as compared with the flat surface of officialese jargon. But the saving in time will be great, while the discipline of setting out the real points concisely will prove an aid to clearer thinking.

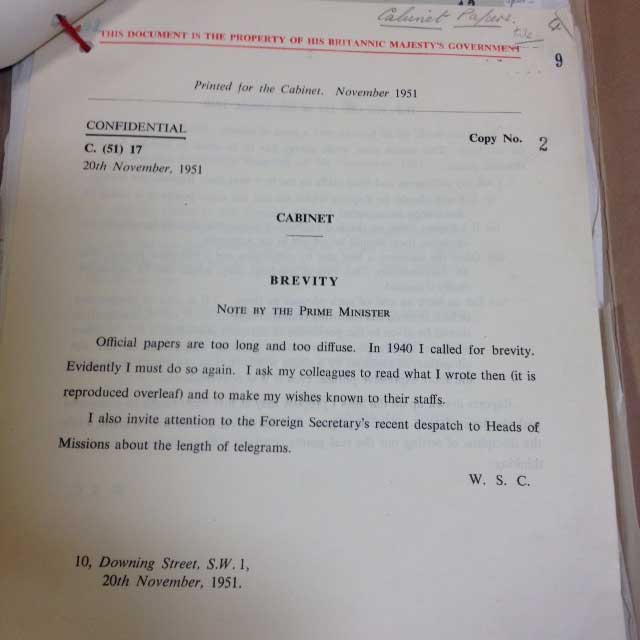

The message “cascaded through the civil service,” writes Laura Cowdry at the UK National Archives. A 1940 article in the Times picked up the story. But the problem persisted, as it does today and maybe will till the end of time (or until machines start to do all our writing for us). Frustrated, Churchill issued another admonition, shorter even than the first, in 1951.

Official papers are too long and too diffuse. In 1940 I called for brevity. Evidently I must do so again. I ask my colleagues to read what I wrote then… and to make my wishes known to their staffs.

These memos, Cowdry notes, “may shed some light onto government communications work of the past,” and on the Churchillian style that may have taken hold for decades in government documents, as well as—of course—far beyond them. His emphatic statements also articulate “key elements of good communication that would resonate with the thinking of any modern communicator,” whether Orwell, Kurt Vonnegut, or Cormac McCarthy, who has become a sought-after scientific editor for his strict minimalism.

Churchill did not seem overly concerned with wordiness as a political problem. Orwell did not approach the problem philosophically. That task fell to the Logical Positivists of the early 20th century. In his attempt to explain the wordiness of both undergraduates and world-renowned thinkers, “neo-Positivist” philosopher David Stove goes so far as to ascribe overwriting to “defects of character… such things as an inability to shut up; determination to be thought deep; hunger for power; fear, especially the fear of an indifferent universe….”

Something to consider, maybe, when you’re looking at your next draft email, Facebook comment, or Slack message, and wondering whether it actually needs to be an essay….

Related Comment:

George Orwell’s Six Rules for Writing Clear and Tight Prose

Kurt Vonnegut Explains “How to Write With Style”

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness