“I, Dancing Bear,” a song by an obscure folk artist who goes by the name Birdengine, begins thus:

There are some things that I just do not care to know

It’s a lovely little tune, if maudlin and macabre are your thing, a song one might almost call anti-political. It is the art of solipsism, denial, an inwardness that dances over the abyss of pure self, navel gazing for its own sake. It is Kafka-esque, pathetic, and hysterical. I love it.

My appreciation for this weird, outsider New Romanticism does not entail a belief that art and culture should be “apolitical,” whatever that is.

Or that artists, writers, musicians, actors, athletes, or whomever should shut up about politics and stick to what they do best, talk about themselves.

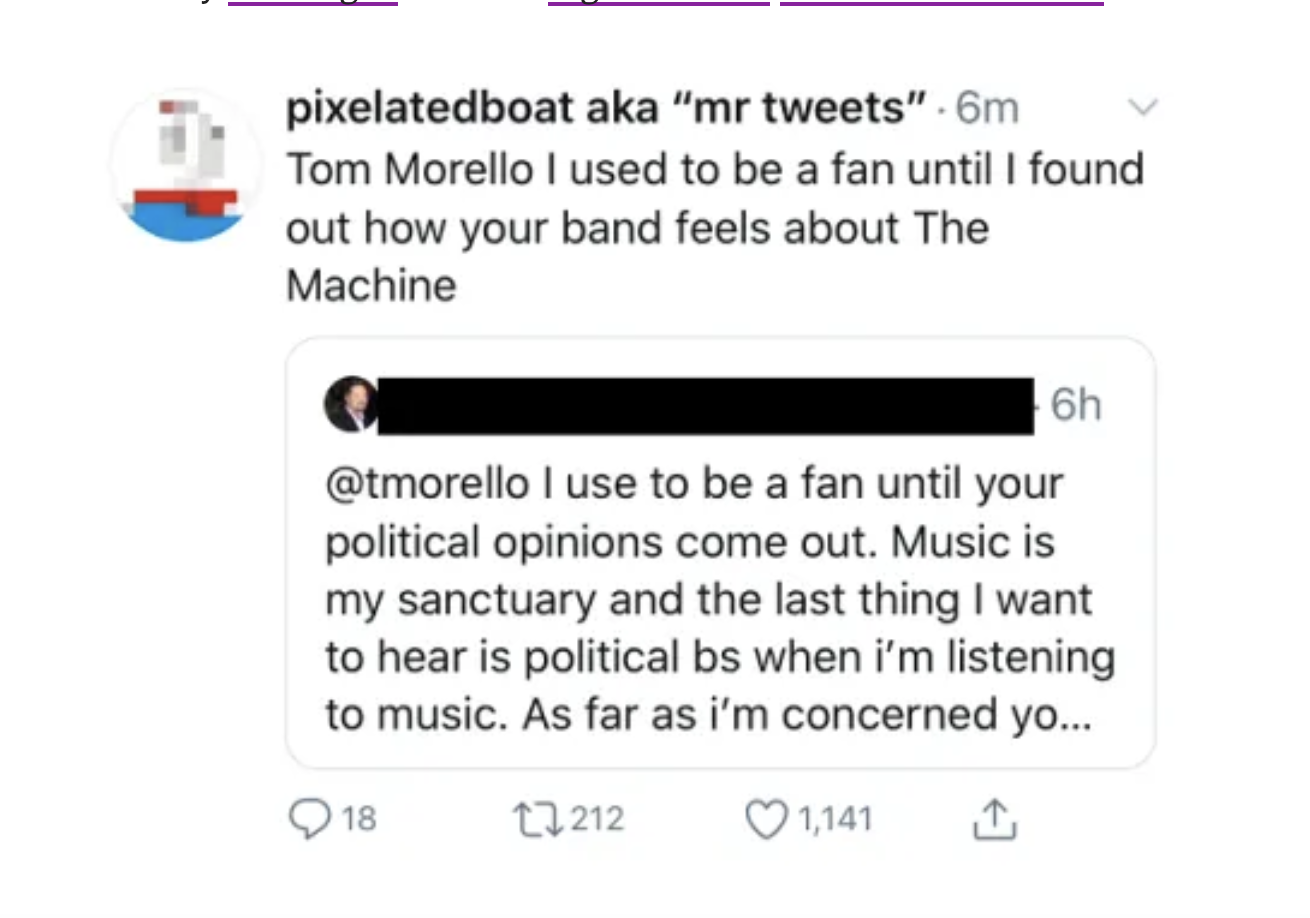

The idea that artists should avoid politics seems so pervasive that fans of some of the most blatantly political, radical artists have never noticed the politics, because, I guess, they just couldn’t be there.

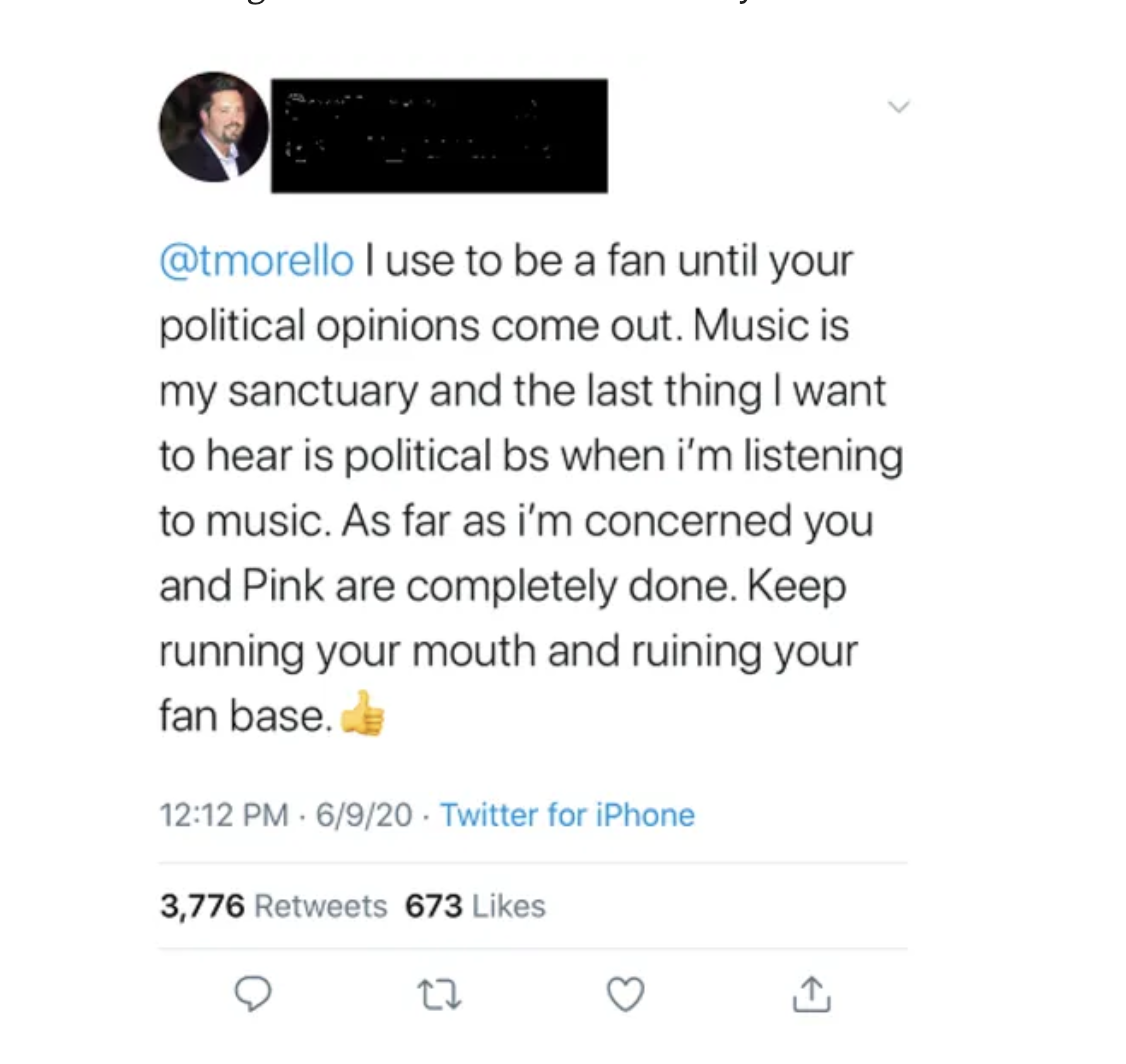

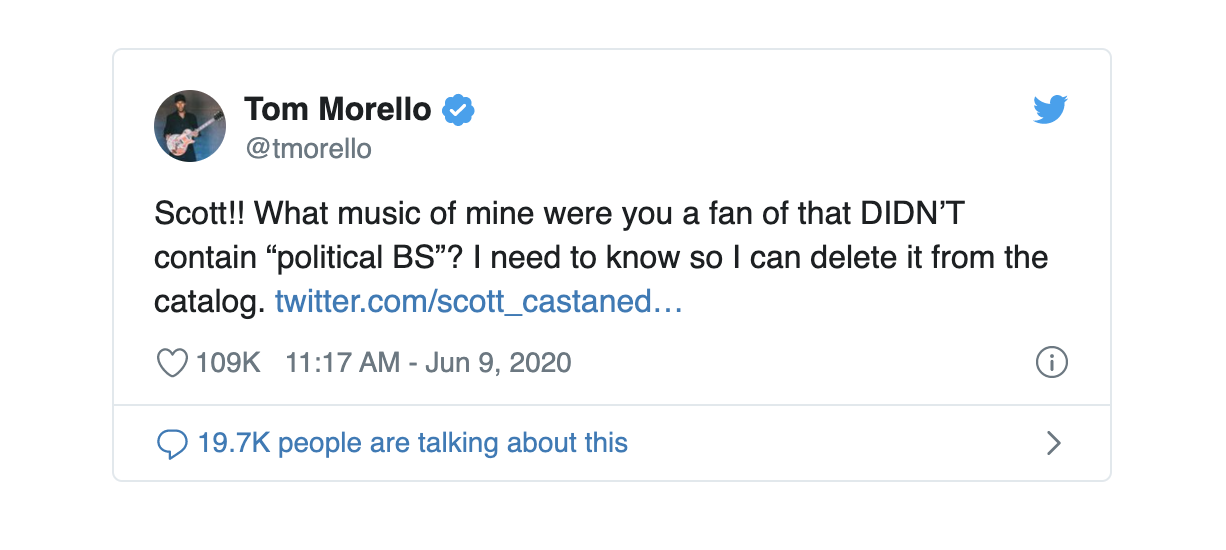

One such fan just got dunked on, as they say, a whole bunch on Twitter when he raged against Tom Morello for the “political bs.”

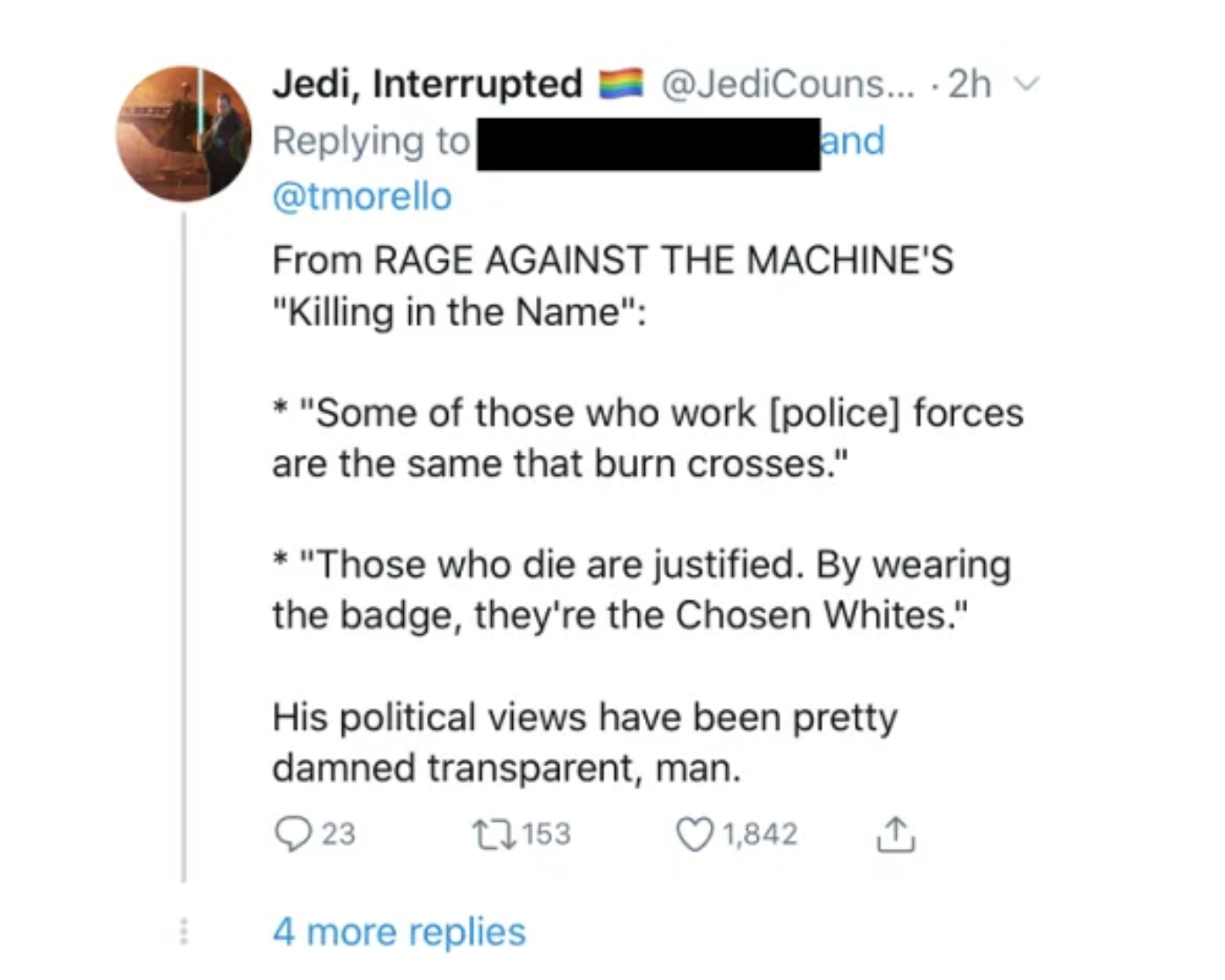

That’s Tom Morello of Rage Against the Machine, whose debut 1992 album informed us that the police and the Klan work hand in hand, and that cops are the “chosen whites” for state-sanctioned murder. That Rage Against the Machine, who raged against the same Machine on every album: “Bam, here’s the plan; Motherfuck Uncle Sam.”

The poor sod was burned so badly he deleted his account, but the laughs at his expense kept coming. Even Morello responded.

Why? Because the disgruntled former fan is not just one lone crank who didn’t get it. Many people over the years have expressed outrage at finding out there’s so much politics in their culture, even in a band like Rage that could not have been less subtle. Many, like former lever-puller of the Machine, Paul Ryan, seem to have cynically missed the point and turned them into workout music. Morello’s had to point this out a lot. (Ditto Springsteen.)

This uncritical consumption of culture without a thought about icky political issues is maybe one reason we have a separate political class, paid handsomely to do the dirty work while the rest of us go shopping. It’s a recipe for mass ignorance and fascism.

You might think me crazy if I told you that the CIA is partly responsible for our expectation that art and culture should be apolitical. The Agency did, after all, follow the lead of the New Critics, who excluded all outside political and social considerations from art (so they said).

Influential literary editors and writing program directors on the Agency payroll made sure to fall in line, promoting a certain kind of writing that focused on the individual and elevated psychological conflict over social concerns. This influence, writes The Chronicle of Higher Education, “flattened literature” and set the boundaries for what was culturally acceptable. (Still, CIA-funded journals like The Paris Review published dozens of “political” writers like Richard Wright, Gabriel Garcia Marquez, and James Baldwin.)

Then there’s the whole business of Hollywood film as a source of Pentagon-funded propaganda, sold as innocuous, apolitical entertainment….

When it comes to journalism, an ideal of objectivity, like Emerson’s innocent, disembodied transparent eye, became a standard only in the 20th century, ostensibly to weed out political bias. But that ideal serves the interests of power more often than not. If media represents existing power relationships without questioning their legitimacy, it can claim objectivity and balance; if it challenges power, it becomes too “political.”

The adjective is weaponized against art and culture that makes certain people who have power uncomfortable. Saying “I don’t like political bs in my culture” is saying “I don’t care to know the politics are there.”

If, after decades of pumping “Killing in the Name,” you finally noticed them, then all that’s happened is you’ve finally noticed. Culture has always included the political, whether those politics are shaped by monarchs or state agencies or shouted in rap metal songs (just ask Ice‑T) and fought over on Twitter. Maybe now it’s just getting harder to look away.

Related Content:

The Politics & Philosophy of the Bauhaus Design Movement: A Short Introduction

Love the Art, Hate the Artist: How to Approach the Art of Disgraced Artists

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness