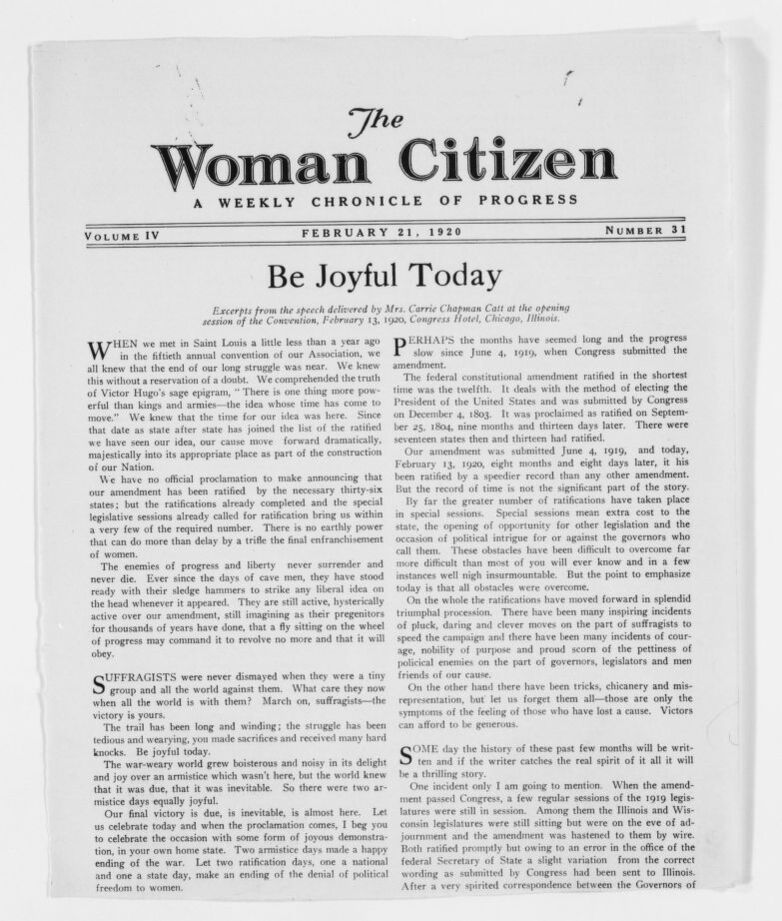

As we barrel toward the centennial celebration of women’s suffrage in the United States, it’s not enough to bone up on the platforms of female primary candidates (though that’s an excellent start).

A Twitter user and self-described Old Crone named Robyn recently urged her fellow Americans to take a good long gander at a list of nine freedoms women in the United States were not universally granted in 1971, the year Helen Reddy released the soon-to-be anthem, “I Am Woman,” above.

Even those of us who remember singing along as children may experience some shock that these facts check out on Snopes.

- CREDIT CARDS: Prior to the Equal Credit Opportunity Act of 1974, married women couldn’t get credit cards without their husbands’ signatures. Single women, divorcees, and widows were often required to have a man cosign. The double standard also meant female applicants were frequently issued card limits up to 50% lower than that of males who earned identical wages.

- PREGNANT WORKERS: The Pregnancy Discrimination Act of 1978 protected pregnant women from being fired because of their impending maternity. But it came with a major loophole that’s still in need of closing. The language of the 41-year-old law stipulates that the employers must accommodate pregnant workers only if concessions are being made for other employees who are “similar in their ability or inability to work.”

- JURY DUTY: In 1975, the Supreme Court declared it constitutionally unacceptable for states to deny women the opportunity to serve on juries. This is an arena where we’ve all come a long way, baby. It’s now completely normal for men to be excused from jury duty as the primary caregivers of their young children.

- MILITARY COMBAT: In 2013, former Secretary of Defense Leon Panetta and former Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, General Martin Dempsey announced that the Pentagon was rescinding the direct combat exclusion rule that barred women from serving in artillery, armor, infantry and other such battle roles. At the time of the announcement, the military had already seen more than 130 female soldiers killed, and 800 wounded on the frontlines in Iraq and Afghanistan.

- IVY LEAGUE ADMISSIONS: Those who conceive of elite colleges as breeding grounds for sexual assault protests and Title IX activism would do well to remember that Columbia College didn’t admit women until 1983, following in the marginally deeper footsteps of others in the Ivy League—Harvard (1977), Dartmouth (1972), Brown (1971), Yale (1969), and Princeton (1969). These days, single sex higher education options for women far outnumber those for men, but the networking power and increased earning potential an Ivy League degree confers remains the same.

- WORKPLACE HARASSMENT: In 1977, women who’d been sexually harassed in the workplace received confirmation in three separate trials that they could sue their employers under Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act. In 1998, the Supreme Court ruled that same-sex harassment was also unlawful. In between was the television event of 1991, Anita Hill’s shocking testimony against her former boss, U.S. Supreme Court justice (then nominee) Clarence Thomas.

- SPOUSAL CONSENT: In 1993, spousal rape was officially outlawed in all 50 states. Not tonight honey, or you’ll have a headache in the form of your wife’s legal back up.

- HEALTH INSURANCE: In 2010, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act decreed that any health insurance plan established after March of that year could not charge women higher premiums than men for identical benefits. This was bad news for women who got their health insurance through their jobs, and whose employers were grandfathered into discriminatory plans established prior to 2010. Of course, that’s all ancient history now.

- CONTRACEPTIVES: In 1972, the Supreme Court made it legal for all citizens to possess birth control, irrespective of marital status, stating “if the right of privacy means anything, it is the right of the individual, married or single, to be free from unwarranted governmental intrusion into matters so fundamentally affecting a person as the decision whether to bear or beget a child.” (It’s worth noting, however, that in 1972, states could still constitutionally prohibit and punish sex outside of marriage.)

Feminism is NOT just for other women.

Via Kottke

Related Content:

MAKERS Tells the Story of 50 Years of Progress for Women in the U.S.

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inkyzine. Join her in NYC on Monday, October 7 when her monthly book-based variety show, Necromancers of the Public Domaincelebrates the art of Aubrey Beardsley. Follow her @AyunHalliday.