Image by “Siebbi,” Wikimedia Commons

So many of us, throughout so much of the 20th century, saw the nature of American-style democracy as more or less etched in stone. But the events of recent years, certainly on the national level but also on the global one, have thrown our assumptions about a political system that once looked destined for universality — indeed, the much-discussed “end” toward which history itself has been working — into question. Whatever our personal views, we’ve all had to remember that the United States, approaching a quarter-millennium of history, remains an experimental country, one more subject to re-evaluation and revision than we might have thought.

The same holds true for the art form that has done more than any other to spread visions of America: the movies. Martin Scorsese surely knows this, just as deeply as he knows that a full understanding of any society demands immersion into that society’s dreams of itself. The fact that so many of America’s dreams have taken cinematic form makes Scorsese well-placed to approach the subject, given that he’s dreamed a fair few of them himself. Taxi Driver, Raging Bull, Goodfellas, Gangs of New York, The Wolf of Wall Street: most of his best-known films tell thoroughly American stories, rooted in not just his country’s distinctive history but the equally distinctive politics, society, and culture that have resulted from it.

Now, along with his nonprofit The Film Foundation, Scorsese passes his understanding of America along to all of us with their curriculum, “Portraits of America: Democracy on Film.” It comes as part of their larger project “The Story of Film,” described by its official site as “an interdisciplinary curriculum introducing students to classic cinema and the cultural, historical, and artistic significance of film.” Scorsese and The Film Foundation offer its materials free to schools, but students of all ages and nationalities can learn a great deal about American democracy from the pictures it includes, the sequence of which runs as follows:

Module 1: The Immigrant Experience

Introductory Lesson: From Penny Claptrap to Movie Palaces—the First Three Decades

Chapter 1: “The Immigrant” (1917, d. Charlie Chaplin)

Chapter 2: “The Godfather, Part II” (1974, d. Francis Ford Coppola)

Chapter 3: “America, America” (1963, d. Elia Kazan)

Chapter 4: “El Norte” (1983, d. Gregory Nava)

Chapter 5: “The Namesake” (2006, d. Mira Nair)Module 2: The American Laborer

Introductory Lesson: The Common Good

Chapter 1: “Black Fury” (1935, d. Michael Curtiz)

Chapter 2: “Harlan County U.S.A.” (1976, d. Barbara Kopple)

Chapter 3: “At the River I Stand” (1993, d. David Appleby, Allison Graham and Steven Ross)

Chapter 4: “Salt of the Earth” (1954, d. Herbert J. Biberman)

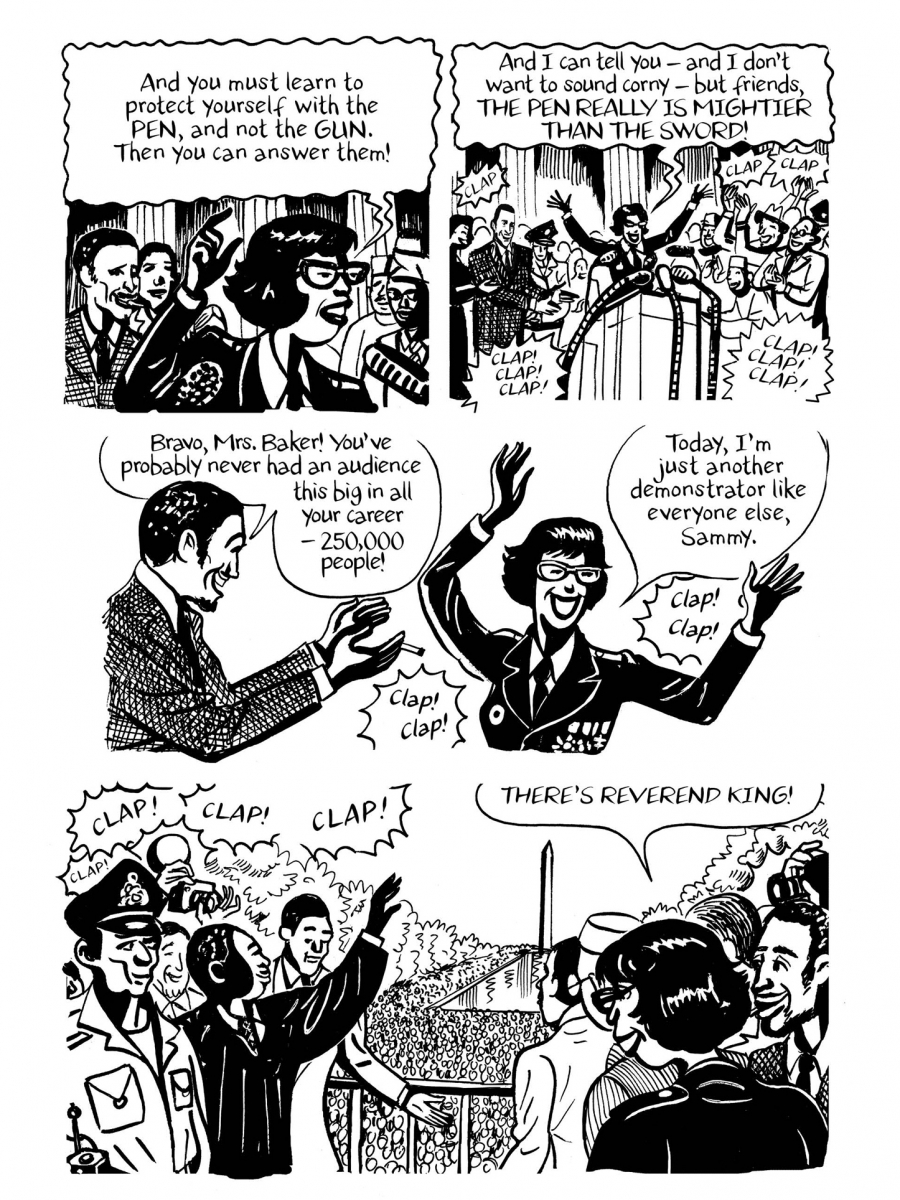

Chapter 5: “Norma Rae” (1979, d. Martin Ritt)Module 3: Civil Rights

Introductory Lesson: The Camera as Witness

Chapter 1: King: A Filmed Record…Montgomery to Memphis (1970, conceived & created by

Ely Landau; guest appearances filmed by Sidney Lumet and Joseph L.

Mankiewicz)

Chapter 2: “Intruder in the Dust” (1949, d. Clarence Brown)

Chapter 3: “The Times of Harvey Milk” (1984, d. Robert Epstein)

Chapter 4: “Smoke Signals” (1998, d. Chris Eyre)

Module 4: The American Woman

Introductory Lesson: Ways of Seeing Women

Chapter 1: Through a Woman’s Lens: Directors Lois Weber (focusing on “Suspense,” 1913 and

“Where Are My Children,” 1916) and Dorothy Arzner (“Dance, Girl, Dance,” 1940)

Chapter 2: “Imitation of Life” (1934, d. John M. Stahl)

Chapter 3: “Woman of the Year” (1942, d. George Stevens)

Chapter 4: “Alien” (1979, d. Ridley Scott)

Chapter 5: “The Age of Innocence” (1993, d. Martin Scorsese)Module 5: Politicians and Demagogues

Introductory Lesson: Checks and Balances

Chapter 1: “Gabriel Over the White House” (1933, d. Gregory La Cava)

Chapter 2: “A Lion is in the Streets” (1953, d. Raoul Walsh)

Chapter 3: “Advise and Consent” (1962, d. Otto Preminger)

Chapter 4: “A Face in the Crowd” (1957, d. Elia Kazan)Module 6: Soldiers and Patriots

Introductory Lesson: Movies and Homefront Morale

Chapter 1: “Sergeant York (1941, d. Howard Hawks)

Chapter 2: Private Snafu’s Private War—three Snafu Shorts from WWII

Chapter 3: “Three Came Home” (1950, d. Jean Negulesco)

Chapter 4: “Glory” (1989, Edward Zwick)

Chapter 5: “Saving Private Ryan” (1998, d. Steven Spielberg)Module 7: The Press

Introductory Lesson: Degrees of Truth

Chapter 1: “Meet John Doe” (1941, d. Frank Capra)

Chapter 2: “All the President’s Men” (1976, d. Alan J. Pakula)

Chapter 3: “Good Night, and Good Luck” (2005, d. George Clooney)

Chapter 4: “An Inconvenient Truth” (2006, d. Davis Guggenheim)

Chapter 5: “Ace in the Hole” (1951, d. Billy Wilder)Module 8: The Auteurs

Introductory Lesson: Film as an Art Form

Chapter 1: “Modern Times” (1936, Charlie Chaplin)

Chapter 2: “The Grapes of Wrath”(1940, d. John Ford)

Chapter 3: “Citizen Kane” (1941, d. Orson Welles)

Chapter 4: “An American in Paris” (1951, d. Vincente Minnelli)

Chapter 5: “The Aviator” (2004, d. Martin Scorsese)

“Division, conflict and anger seem to be defining this moment in culture,” says Scorsese, quoted in a Film Journal International article about the curriculum. “I learned a lot about citizenship and American ideals from the movies I saw. Movies that look squarely at the struggles, violent disagreements and the tragedies in history, not to mention hypocrisies, false promises. But they also embody the best in America, our great hopes and ideals.” Few could watch all 38 of the films on his curriculum without feeling that the experiments of democracy and cinema are still on to something – and hold out the promise of more possibilities than we’d imagined before.

via Indiewire

Related Content:

Martin Scorsese to Teach His First Online Course on Filmmaking

Martin Scorsese Makes a List of 85 Films Every Aspiring Filmmaker Needs to See

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.