An Indian guru travels to the West with teachings of enlightenment, world peace, and liberation from the soul-killing materialist grind. He attracts thousands of followers, some of them wealthy celebrities, and founds a commercial empire with his teachings. No, this isn’t the story of Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh, the head of the religious movement in Wild Wild Country. There was no miraculous city in the Oregon wilds or fleet of Learjets and Rolls Royces. No stockpile of automatic weapons, planned assassinations, or mass poisonings. Decades before those strange events, another teacher, Maharishi Mahesh Yogi inspired mass devotion among students around the world with the peaceful practice of Transcendental Meditation.

Rolling Stone’s Claire Hoffman—who grew up in a TM community—writes of the movement with ambivalence. For most of his disciples, he was a “Wizard of Oz-type character,” she says, distant and mysterious. But much of what we popularly know about TM comes from its most famous adherents, including Jerry Seinfeld, Katy Perry, David Lynch, the Beach Boys, and, of course, The Beatles, who famously traveled to India in 1968, meditated with Mia Farrow, Donovan, and Mike Love, and wrote some of their wildest, most inventive music after a creative slump following the huge success of Sgt. Pepper’s.

“They stayed in Rishikesh,” writes Maria Popova at Brain Pickings, “a small village in the foothills of the Himalayas, considered the capital of yoga. Immersed in this peaceful community and nurtured by an intensive daily meditation practice, the Fab Four underwent a creative growth spurt—the weeks at Rishikesh were among their most fertile songwriting and composing periods, producing many of the songs on The White Album and Abbey Road.” Unlike most of the Maharishi’s followers, The Beatles got a personal audience. The Indian spiritual teacher “helped them through the shock” of their manager Brian Epstein’s death, and helped them tap into cosmic consciousness without LSD.

They left on a sour note—there were allegations of impropriety, and Lennon, being Lennon, got a bit nasty, originally writing The White Album’s “Sexy Sadie” with the lyrics “Maharishi—what have you done? You made a fool of everyone.” But before their falling out with TM’s founder, before even the trip to India, all four Beatles became devoted meditators, sitting for two twenty-minute sessions a day and finding genuine peace and happiness—or “energy,” as Lennon and Harrison describe it in a 1967 interview with David Frost. The next year, happily practicing, and feverishly writing, in India, Lennon received letters from fans, and responded with enthusiasm.

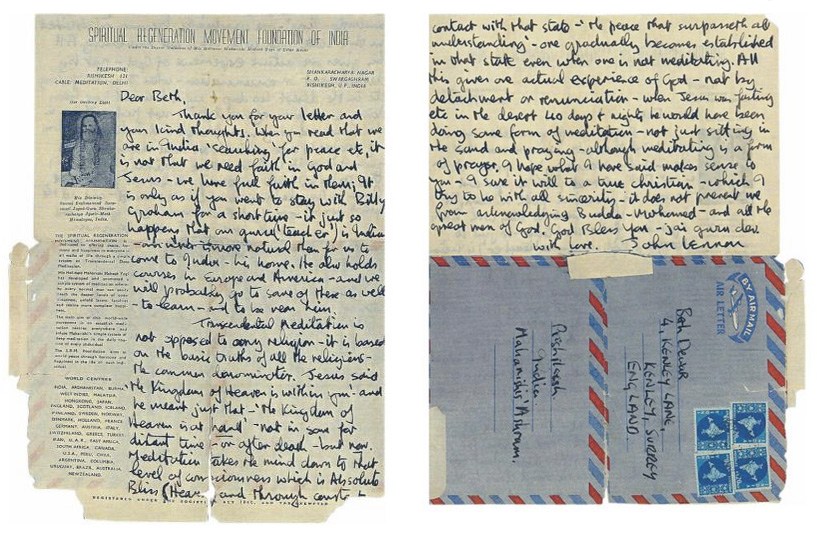

In answer to a letter from a fan named Beth, evidently a devout Christian and apparently threatened by TM and concerned for the bands’ immortal souls, Lennon wrote the following (see his handwritten reply at the top):

Dear Beth:

Thank you for your letter and your kind thoughts. When you read that we are in India searching for peace, etc, it is not that we need faith in God or Jesus — we have full faith in them; it is only as if you went to stay with Billy Graham for a short time — it just so happens that our guru (teacher) is Indian — and what is more natural for us to come to India — his home. He also holds courses in Europe and America — and we will probably go to some of these as well — to learn — and to be near him.

Transcendental meditation is not opposed to any religion — it is based on the basic truths of all religions — the common denominator. Jesus said: “The Kingdom of Heaven is within you” — and he meant just that — “The Kingdom of Heaven is at hand” — not in some far distant time — or after death — but now.

Meditation takes the mind down to that level of consciousness which is Absolute Bliss (Heaven) and through constant contact with that state — “the peace that surpasses all understanding” — one gradually becomes established in that state even when one is not meditating. All this gives one actual experience of God — not by detachment or renunciation — when Jesus was fasting etc in the desert 40 days & nights he would have been doing some form of meditation — not just sitting in the sand and praying — although me it will be a true Christian — which I try to be with all sincerity — it does not prevent me from acknowledging Buddha — Mohammed — and all the great men of God. God bless you — jai guru dev.

With love,

John Lennon

This hardly sounds like the man who imagined no religion. A fan in India wrote Lennon less to inquire and more to acquire, namely money for a trip around the world so that he could “discover the ‘huge treasure’ necessary for achieving inner peace.” Lennon responded with a brief rebuke of the man’s material aspirations, then recommended TM, “through which all things are possible.” (He signs both letters with “jai guru dev,” or “I give thanks to the Guru Dev,” the Maharishi’s teacher. The phrase also appears as the refrain in his “Across the Universe.”)

The letters come from an excellent collection of his correspondence, The John Lennon Letters, which includes other missives extolling the virtues of transcendental meditation. We might take his word for it based on the strength of the creative work he produced during the period. We could also take the word of David Lynch, who describes meditation as the way he catches the creative “big fish.” Or we could go out and find our own methods for expanding our minds and tapping into creative potential.

via Brain Pickings

Related Content:

David Lynch Explains How Meditation Enhances Our Creativity

The John Lennon Sketchbook, a Short Animation Made of Lennon’s Drawings, Premieres on YouTube

Watch John Lennon’s Last Live Performance (1975): “Imagine,” “Stand By Me” & More

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness