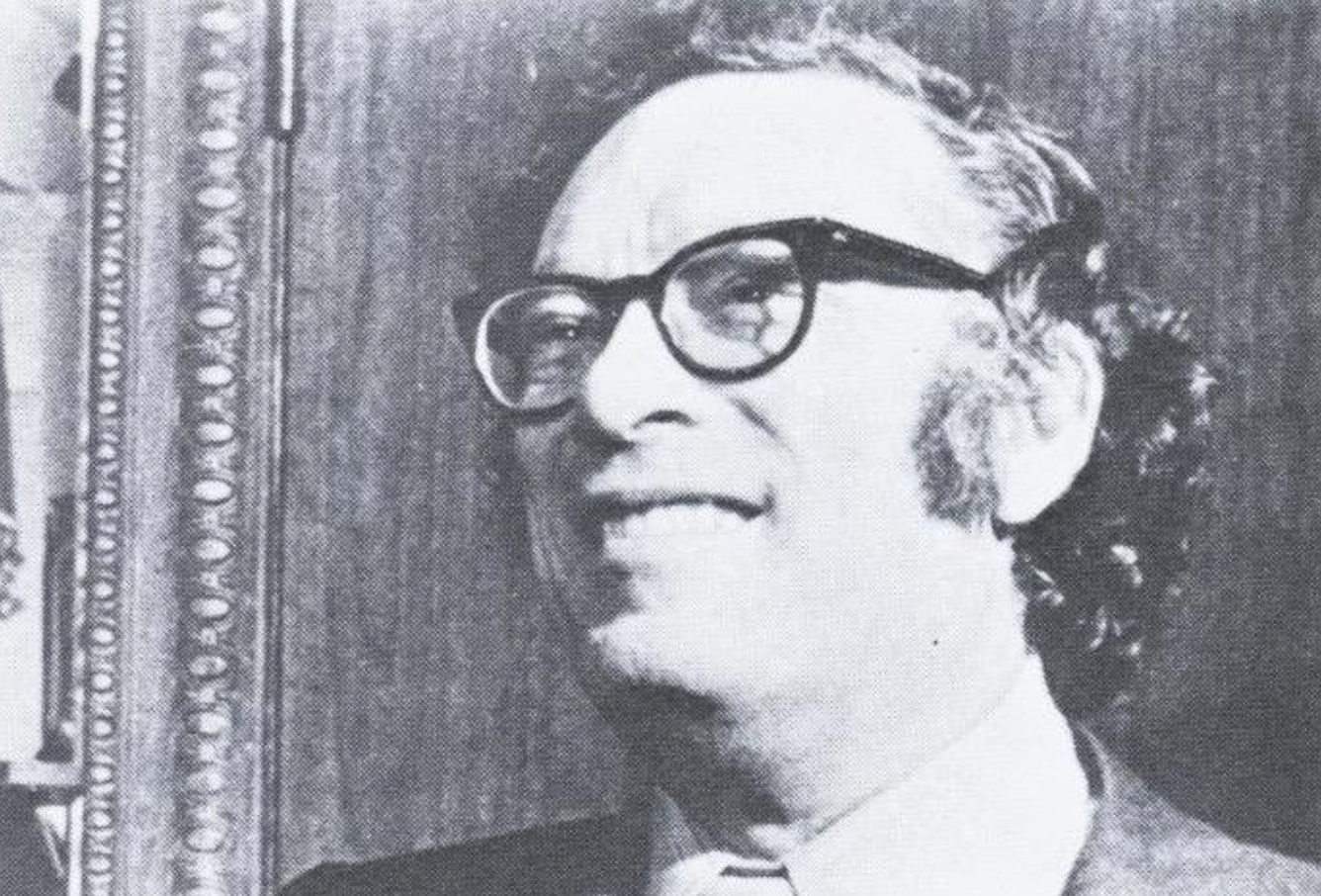

Rochester Institute of Technology, via Wikimedia Commons

“It’s difficult to make predictions,” they say, “especially about the future.” The witticism has been variously attributed. If Yogi Berra said it, it’s adorable nonsense, if Mark Twain, dry plainspoken irony. If Niels Bohr, however, we have a statement that makes us wonder what exactly “the future” could mean in a radically uncertain universe.

If scientists can’t predict the future, who can? Science fiction writers, of course. They may be spectacularly wrong at times, but few professionals seem better equipped to imaginatively extrapolate from current conditions—cultural, technological, social, and political—and show us things to come. J.G. Ballard, Octavia Butler, Arthur C. Clarke, Kurt Vonnegut… all have foreseen many of the marvels and dystopian nightmares that have arrived since their time.

In 1964, Asimov used the occasion of the New York World’s Fair to offer his vision of fifty years hence. “What will the World’s Fair of 2014 be like?” he asked in The New York Times, the question itself containing an erroneous assumption about the durability of that event. As a scientist himself, his ideas are both technologically farseeing and conservative, containing advances we can imagine not far off in our future, and some that may seem quaint now, though reasonable by the standards of the time (“fission-power plants… supplying well over half the power needs of humanity”).

Nineteen years later, Asimov ventured again to predict the future—this time of 2019 for The Star. Assuming the world has not been destroyed by nuclear war, he sees every facet of human society transformed by computerization. This will, as in the Industrial Revolution, lead to massive job losses in “clerical and assembly-line jobs” as such fields are automated. “This means that a vast change in the nature of education must take place, and entire populations must be made ‘computer-literate’ and must be taught to deal with a ‘high-tech’ world,” he writes.

The transition to a computerized world will be difficult, he grants, but we should have things pretty much wrapped up by now.

By the year 2019, however, we should find that the transition is about over. Those who can be retrained and re-educated will have been: those who can’t be will have been put to work at something useful, or where ruling groups are less wise, will have been supported by some sort of grudging welfare arrangement.

In any case, the generation of the transition will be dying out, and there will be a new generation growing up who will have been educated into the new world. It is quite likely that society, then, will have entered a phase that may be more or less permanently improved over the situation as it now exists for a variety of reasons.

Asimov foresees the climate crisis, though he doesn’t phrase it that way. “The consequences of human irresponsibility in terms of waste and pollution will become more apparent and unbearable with time and again, attempts to deal with this will become more strenuous.” A “world effort” must be applied, necessitating “increasing co-operation among nations and among groups within nations” out of a “cold-blooded realization that anything less than that will mean destruction for all.”

He is confident, however, in such “negative advances” as the “defeat of overpopulation, pollution and militarism.” These will be accompanied by “positive advances” like improvements in education, such that “education will become fun because it will bubble up from within and not be forced in from without.” Likewise, technology will enable increased quality of life for many.

… more and more human beings will find themselves living a life rich in leisure.

This does not mean leisure to do nothing, but leisure to do something one wants to do; to be free to engage in scientific research. in literature and the arts, to pursue out-of-the-way interests and fascinating hobbies of all kinds.

If this seems “impossibly optimistic,” he writes, just wait until you hear his thoughts on space colonization and moon mining.

The Asimov of 1983 sounds as confident in his predictions as the Asimov of 1964, though he imagines a very different world each time. His future scenarios tell us as much or more about the time in which he wrote as they do about the time in which we live. Read his full essay at The Star and be the judge of how accurate his predictions are, and how likely any of his optimistic solutions for our seemingly intractable problems might be in the coming year.

Related Content:

Arthur C. Clarke Predicts the Future in 1964 … And Kind of Nails It

Sci-Fi Author J.G. Ballard Predicts the Rise of Social Media (1977)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness