Let’s say you spend a considerable amount of money for a painting by a noted artist. Or maybe you get it for a steal. Either way, the painting hangs prominently in your home, where it is admired by guests and brings you pleasure every time you look at it, which is often. Years later, you accidentally discover that your painting is not the work of the artist whose signature graces the lower right hand corner of the canvas, but rather a heretofore anonymous forger. How do you react?

Do you laugh and say, “When I think of all the happiness that living with this beautiful image has brought me over the years, I feel I have gotten my money’s worth many times over. I don’t care who painted it!”

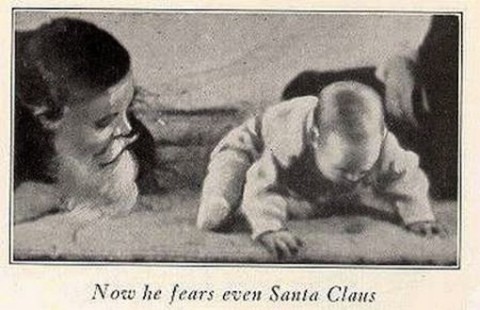

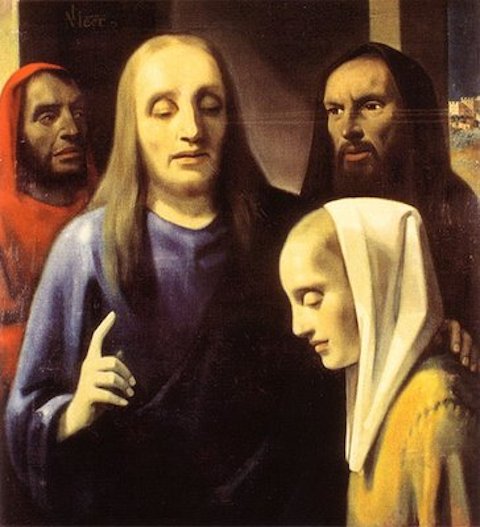

Or do you look as though you’ve just realized that evil exists in the world, which is how Hitler’s right hand man, Hermann Göring, reputedly looked when, as a prisoner at Nuremberg, he was informed that his beloved Vermeer, ”Christ with the Woman Taken in Adultery” (below), was actually the work of the Dutch dealer who had sold it to him.

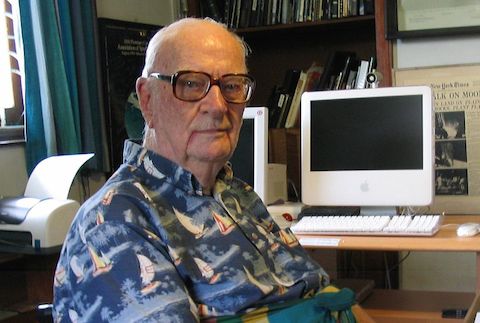

Göring’s reaction may have been the most human thing about him. According to Yale psychologist Paul Bloom, the pleasure we take in the things we love is deeply informed by their perceived origins. Forget monetary value. Forget bragging rights. We need to believe that our painting was not just painted by Vermeer, but handled by him, breathed upon him. If only that Vermeer of mine could talk…I bet it could settle once and for all the exact nature of his relationship with that little serving girl. Remember? The one with the pearl earring?

Oh, wait. She was fictional. I forgot.

But that’s the sort of provenance we crave. The kind that comes with a story we can sink our teeth into.

The story must also fit the circumstances, as Bloom makes plain in his wonderfully entertaining TED talk on the Origins of Pleasure.

Unknowingly hopping in the sack with a blood relative or eating rat meat are intriguing narratives, provided they happen to someone else. Knowledge of such stories could deepen your connection to a particular piece of art.

(Can’t you feel the sexual anguish oozing out of my Vermeer? Did you know he had to choose between buying brushes and buying food?)

Not the sort of origin story you’d want to find at the bottom of your own personal soup bowl, however.

Ergo, let us say that when it comes to pleasure emanating from food, we savor tastes we perceive as coming from wholesome organic farms, artisanal operations, restaurants that are known to have passed the Board of Health’s sanitary inspection with flying colors.

And when it comes to drink, we will willingly believe in the superior flavor of anything poured under the auspices of an acclaimed label. Scientific evidence confirms this.

(On a related note, I once hung on to a bottle after drinking the luxury vodka it once contained, thinking I’d refill it with a cheap liquor hack I had read about. The experiment ended when my husband complained that the water in our Brita pitcher tasted funny.)

Speaking of romantic partners, it turns out that beauty truly is not so much in the eye, but the brain of the beholder. And it’s probably not a bad idea to make sure you’ve got the facts regarding a potential lover’s age, gender, and bloodlines. Caveat emptor, as anyone who’s ever seen the Crying Game will attest.

Note: Paul Bloom has taught a free course through Yale called “Introduction to Psychology,”. It’s available in our collection of Free Online Psychology Courses, part of our larger collection, 1,700 Free Online Courses from Top Universities.

Related Content:

Why We Love Repetition in Music: Explained in a New TED-Ed Animation

A Darwinian Theory of Beauty, or TED Does Its Best RSA

1756 TED Talks Listed in a Neat Spreadsheet

Ayun Halliday is an author, homeschooler, and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Follow her @AyunHalliday