Is this what we want? A post-truth world where toxicity and tribalism trump bridge building and consensus seeking? —Yaël Eisenstat

It’s an increasingly familiar occurrence.

A friend you’ve enjoyed reconnecting with in the digital realm makes a dramatic announcement on their social media page. They’re deleting their Facebook account within the next 24 hours, so shoot them a PM with your email if you’d like to stay in touch.

Such decisions used to be spurred by the desire to get more done or return to neglected pastimes such as reading, painting, and going for long unconnected nature walks.

These announcements could induce equal parts guilt and anxiety in those of us who depend on social media to get the word out about our low-budget creative projects, though being prone to Internet addiction, we were nearly as likely to be the one making the announcement.

For many, the break was temporary. More of a social media fast, a chance to reevaluate, rest, recharge, and ultimately return.

Legitimate concerns were also raised with regard to privacy. Who’s on the receiving end of all the sensitive information we’re offering up? What are they doing with it? Is someone listening in?

But in this election year, the decision to quit Facebook is apt to be driven by the very real fear that democracy as we know it is at stake.

Former CIA analyst, foreign service officer, and—for six months—Facebook’s Global Head of Elections Integrity Ops for political advertising, Yaël Eisenstat, addresses these preoccupations in her TED Talk, “Dear Facebook, This is How You’re Breaking Democracy,” above.

Eisenstat contrasts the civility of her past face-to-face ”hearts and minds”-based engagements with suspected terrorists and anti-Western clerics to the polarization and culture of hatred that Facebook’s algorithms foment.

As many users have come to suspect, Facebook rewards inflammatory content with amplification. Truth does not factor into the equation, nor does sincerity of message or messenger.

Lies are more engaging online than truth. As long as [social media] algorithms’ goals are to keep us engaged, they will feed us the poison that plays to our worst instincts and human weaknesses.

Eisenstat, who has valued the ease with which Facebook allows her to maintain relationships with far-flung friends, found herself effectively demoted on her second day at the social media giant, her title revised, and her access to high level meetings revoked. Her hiring appears to have been purely ornamental, a palliative ruse in response to mounting public concern.

As she remarked in an interview with The Guardian’s Ian Tucker earlier this summer:

They are making all sorts of reactive changes around the margins of the issues, [to suggest] that they are taking things seriously – such as building an ad library or verifying that political advertisers reside in the country in which they advertising – things they should have been doing already. But they were never going to make the fundamental changes that address the key systemic issues that make Facebook ripe for manipulation, viral misinformation and other ways that the platform can be used to affect democracy.

In the same interview she asserted that Facebook’s recently implemented oversight board is little more than an interesting theory that will never result in the total overhaul of its business model:

First of all, it’s another example of Facebook putting responsibility on someone else. The oversight board does not have any authority to actually address any of the policies that Facebook writes and enforces, or the underlying systemic issues that make the platform absolutely rife for disinformation and all sorts of bad behaviour and manipulation.

The second issue is: it’s basically an appeal process for content that was already taken down. The bigger question is the content that remains up. Third, they are not even going to be operational until late fall and, for a company that claims to move fast and break things, that’s absurd.

Nine minutes into her TED Talk, she offers concrete suggestions for things the Facebook brass could do if it was truly serious about implementing reform:

- Stop amplifying and recommending disinformation and bias-based hatred, no matter who is behind it—from conspiracy theorists to our current president.

- Discontinue personalization techniques that don’t differentiate between targeted political content and targeted ads for athletic footwear.

- Retrain algorithms to focus on a metrics beyond what users click or linger on.

- Implement safety features that would ensure that sensitive content is reviewed before it is allowed to go viral.

Hopefully viewers are not feeling maxed out on contacting their representatives, as government enforcement is Eisenstat’s only prescription for getting Facebook to alter its product and profit model. And that will require sustained civic engagement.

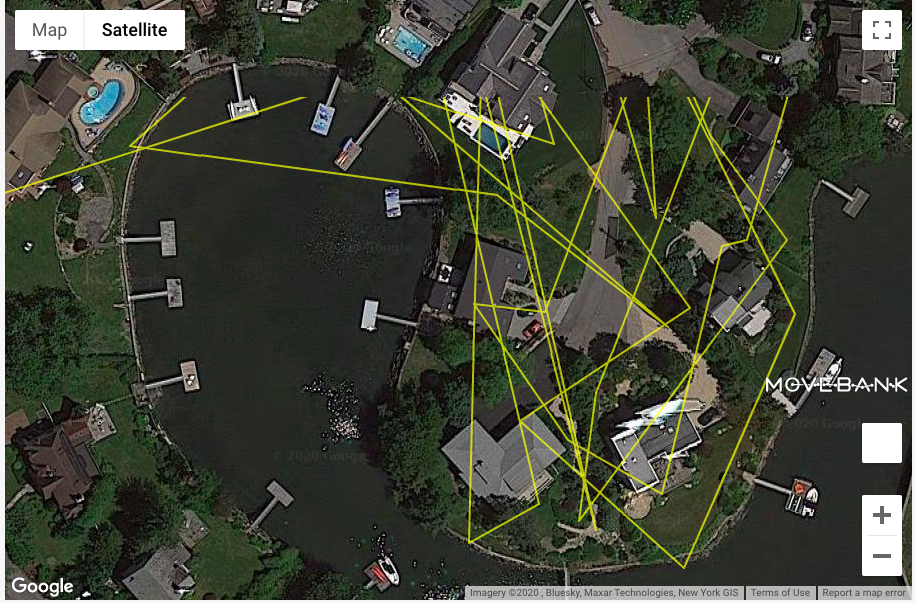

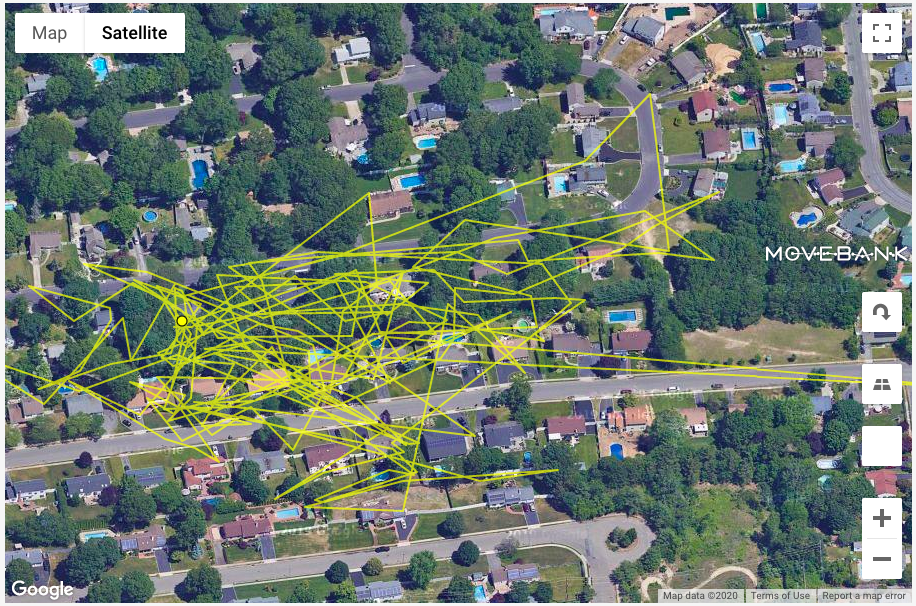

She supplements her TED Talk with recommendations for artificial intelligence engineer Guillaume Chaslot’s insider perspective op-ed “The Toxic Potential of YouTube’s Feedback Loop” and The Filter Bubble: How the New Personalized Web Is Changing What We Read and How We Think by MoveOn.org’s former Executive Director, Eli Pariser.

Your clued-in Facebook friends have no doubt already pointed you to the documentary The Social Dilemma, which is now available on Netflix. Or perhaps to Jaron Lanier’s Ten Arguments for Deleting Your Social Media Accounts Right Now.

Read the transcript of Yaël Eisenstat’s TED Talk here.

Related Content:

The Problem with Facebook: “It’s Keeping Things From You”

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Follow her @AyunHalliday.