You’ve heard the word “blockchain” many times now, but probably not quite as many as you’ve heard the word “bitcoin.” Yet you surely have a sense that the referents of those two words have a connection, and even if you haven’t yet been interested in either, you may well know that blockchain, a technology, makes Bitcoin, a currency, possible in the first place. Their sheer novelty has already given rise to a mini-industry of explainer videos, more of them dealing directly with bitcoin than blockchain, but in time the latter could potentially overtake the former in importance, to the degree that it becomes as vital to society as the protocols that undergird the internet itself.

Or at least you could come away convinced of that after watching the blockchain explainer videos featured here. The shortest of the three, the one by the Institute for the Future at the top of the post, attempts to break down, in just two minutes, the principles behind this technology, still in its infancy, in which so many see such revolutionary potential.

“Blockchains store information across a network of personal computers, making them not just decentralized but distributed,” says the video’s narrator. “This means no central company or person owns the system, yet everyone can use it and help run it.” And according to blockchain’s boosters, that very decentralization and distribution makes it that much more trustable and less hackable.

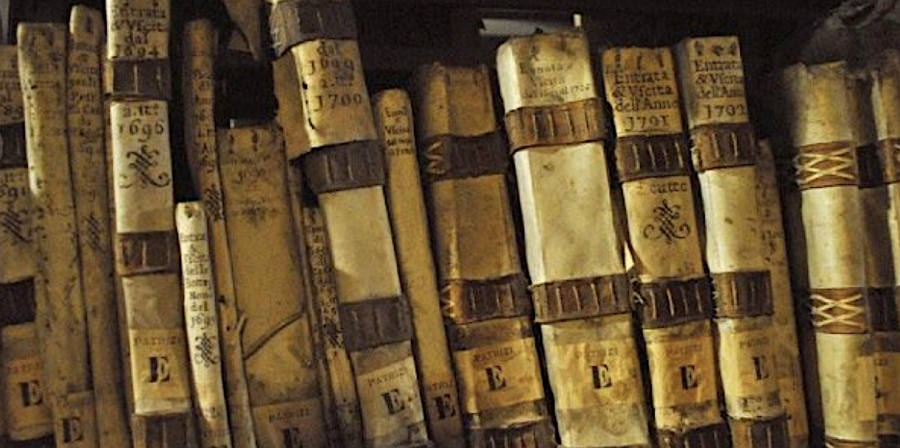

In the Wired video just above, blockchain researcher Bettina Warburg explains her subject in five different ways to people at five different stages of life, from a five-year-old girl to a fully grown academic. Actually, that last interlocutor, an NYU historian named Finn Brunton, does much of the explaining himself, and right at the beginning of his segment (at 9:48) rolls out one of the clearer and more intriguing rundown of the nature of blockchain currently floating around on the internet:

A technical definition of blockchain is that it is a persistent, transparent, public, append-only ledger. So it is a system that you can add data to, and not change previous data within. It does this through a mechanism for creating consensus between scattered, or distributed, parties that do not need to trust each other. They just need to trust the mechanism by which their consensus is arrived at. In the case of blockchain, it relies on some form of challenge such that no one actor on the network is able to solve this challenge more consistently than anyone else on the network. It randomizes the process, and in theory ensures that no one can force the blockchain to accept a particular entry onto the ledger that others disagree with.

Brunton also emphasizes that “almost every aspect of it that is connected with the concept of money” — including but not limited to Bitcoin — “is wildly over-hyped.” Those who can look past the Gold Rush-style ballyhooing of those early applications of blockchain can better grasp what role the technology, which essentially enables the building of systems to securely exchange information over the internet that no one person or company owns, might one day play in many parts of our lives, from finance to energy to health care. “Credit scores that aren’t controlled by a handful of high-risk, data-breach-prone companies,” promises Carissa Carter of Stanford’s d.school, “credible news systems that resist censorship; efficient power grids that could lower your power bills.”

Before it can bring those wonders, Bitcoin must first overcome formidable technical limitations: as Computerworld’s Lucas Mearian writes, for instance,” the Bitcoin blockchain harnesses anywhere between 10 and 100 times as much computing power compared to all of Google’s serving farms put together.” But then, few of the first developers of the technologies that drive the internet could have imagined all we do with them across the world today, and those who did must have had a solid understanding of its most basic elements. How do you know when you’ve attained that understanding? “If you can’t explain it simply, you don’t understand it well enough,” as Albert Einstein once said, and as Citi Innovation Lab CTO Shai Rubin quotes him as saying at the beginning of his own blockchain explainer, performed in less than fifteen minutes using no pieces of technology more revolutionary than a whiteboard and marker.

Related Content:

What Actually Is Bitcoin? Princeton’s Free Course “Bitcoin and Currency Technologies” Provides Much-Needed Answers

Bitcoin, the New Decentralized Digital Currency, Demystified in a Three Minute Video

Bitcoin and Cryptocurrency Technologies: A Free Course from Princeton

The Princeton Bitcoin Textbook Is Now Free Online

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.