Radio has always been a fairly transportive medium.

During the Great Depression, entire families clustered round the electronic hearth to enjoy a variety of entertainments, including live remote broadcasts from the glamorous nightclubs and hotels where celebrity bandleaders like Count Basie and Duke Ellington held sway.

1950s teens’ transistors took them to a head space less square than the white bread suburbs their parents inhabited.

During the Vietnam War, South Vietnamese stations played homegrown renditions of the rock and soul sounds dominating American airwaves.

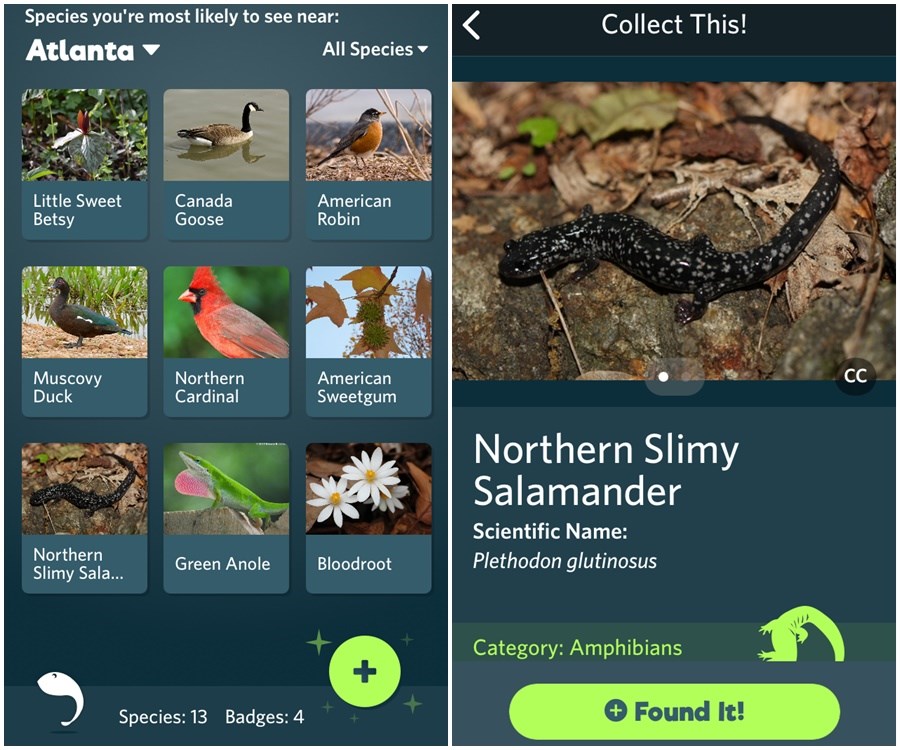

The Radiooooo.com site (there’s also a version available for the iPhone and Android) allows modern listeners to experience a bit of that magical time traveling sensation, via an interactive map that allows you to tune in to specific countries and decades.

The content here is user-generated. Register for a free account, and you too can begin sharing eccentric faves.

Find a user whose tastes mirror your own? Click their profile for a stat card of tracks they’ve favorited and uploaded, as well as any other sundry details they may feel like sharing, such as country of origin and age.

There are fun awards to be earned here, with the most sought after pelts going to the first to upload a song to an empty country, or upload a track from 1910–1920. (Cameroon, 1940 … go!)

As with an actual radio, you are not selecting the actual playlist, though you can nudge the needle a bit by toggling to your desired mood—slow, fast and/or weird.

And you need not limit yourself to a single destination. Embark on a strange musical trip by using Radiooooo’s taxi function to carry you to multiple countries and decades. (I closed my eyes and wound up shuttling between Ukraine and Mauritania in the 60s and 80s.)

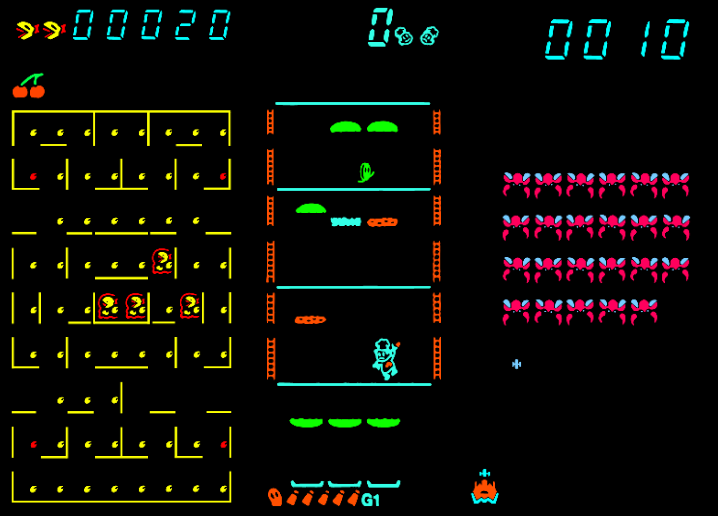

Dotted around the map are island icons, where the ever-growing collection is sorted according to themes like Hawaii, Neverland (“for children big and small”), and 8‑Bit video game music. Le Club, floating midway between Europe and North America, contains brand new releases from contemporary labels.

The Now Playing window includes an option to buy, when possible, as well as the artist’s name and album artwork. Share, like, get your groove on…

And stay tuned for Radiooooo’s latest baby, Le Globe, an interactive 3‑D map of the world and a decade selector dial mounted on a “beautiful connected object.”

The boundaries are extremely permeable here.

Have a browse through Radiooooo’s Instagram feed for a feast of cover art or head to France for one of their in-person listening parties. (There’s one next week in the secret listening room of Paris’ Grand Hotel Amour.)

Readers, if your explorations unearth an exceptional track, please share it in the comments, below.

Download the Radioooo app for Mac or Android here, or listen on the website. (You may need to fool around with various browsers to find the one that works best for you.)

Related Content:

Hear 1,500+ Genres of Music, All Mapped Out on an Insanely Thorough Interactive Graph

Google’s Music Timeline: A Visualization of 60 Years of Changing Musical Tastes

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Her radio dial is set to Romania 1910 in anticipation of the third installment of her literary-themed variety show, Necromancers of the Public Domain , Monday, April 23 at the New York Society Library. Follow her @AyunHalliday.