This Christmas, as our computers fast learn to compose music by themselves, we might gain some perspective by casting our minds back to 66 Christmases ago, a time when a computer’s rendition of anything resembling music at all had thousands and thousands listening in wonder. In December of 1951, the BBC’s holiday broadcast, in most respects a naturally traditional affair, included the sound of the future: a couple of much-loved Christmas carols performed not by a choir, nor by human beings of any kind, but by an electronic machine the likes of which almost nobody had even laid eyes upon.

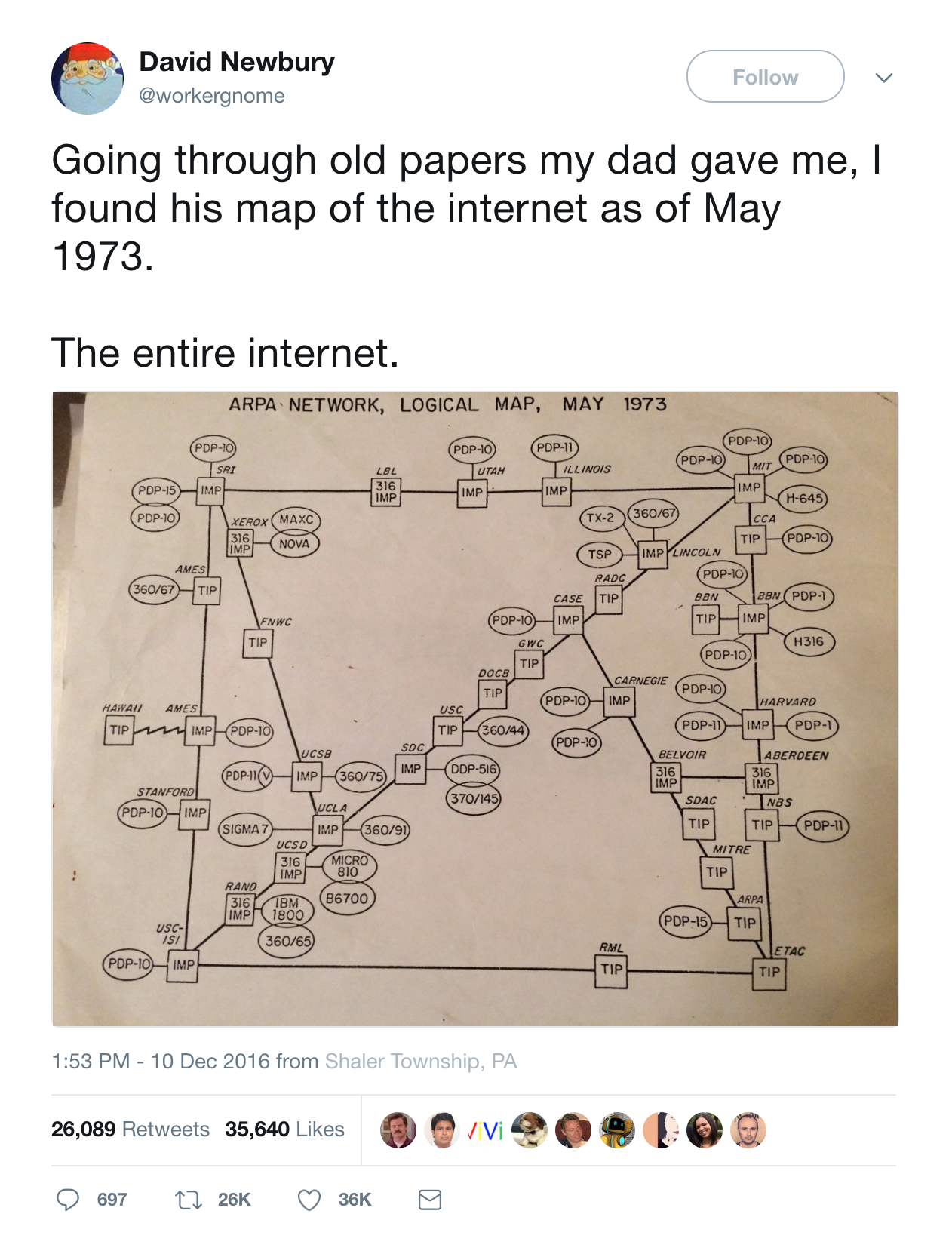

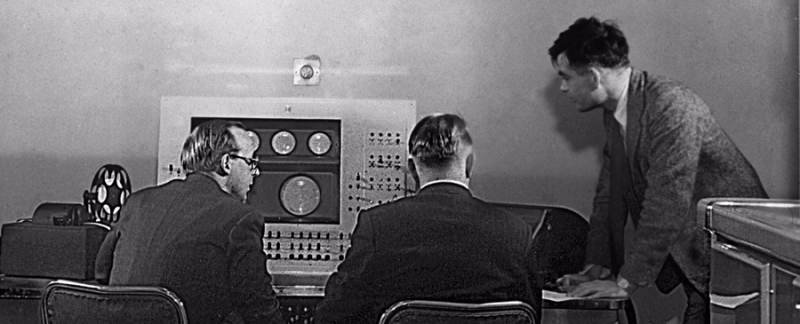

“Among its Christmas fare the BBC broadcast two melodies that, although instantly recognizable, sounded like nothing else on earth,” write Jack Copeland and Jason Long at the British Library’s Sound and Vision Blog. “They were Jingle Bells and Good King Wenceslas, played by the mammoth Ferranti Mark I computer that stood in Alan Turing’s Computing Machine Laboratory” at the Victoria University of Manchester. Turing, whom we now recognize for a variety of achievements in computing, cryptography, and related fields (including cracking the German “Enigma code” during the Second World War), had joined the university in 1948.

That same year, with his former undergraduate colleague D. G. Champernowne, Turing began writing a purely theoretical computer chess program. No computer existed on which he could possibly try running it for the next few years until the Ferranti Mark 1 came along, and even that mammoth proved too slow. But it could, using a function designed to give auditory feedback to its operators, play music — of a kind, anyway. The computer company’s “marketing supremo,” according to Copeland and Long, called its brief Christmas concert “the most expensive and most elaborate method of playing a tune that has ever been devised.”

Since no recording of the broadcast survives, what you hear here is a painstaking reconstruction made from tapes of the computer’s even earlier renditions of “God Save the King,” “Baa Baa Black Sheep,” and “In the Mood.” By manually chopping up the audio, write Copeland and Long, “we created a palette of notes of various pitches and durations. These could then be rearranged to form new melodies. It was musical Lego.” But do “beware of occasional dud notes. Because the computer chugged along at a sedate 4 kilohertz or so, hitting the right frequency was not always possible.” Even so, somewhere in there I hear the historical and technological seeds of the much more elaborate electronic Christmas to come, from Mannheim Steamroller to the Jingle Cats and well beyond.

Related Content:

Hear Paul McCartney’s Experimental Christmas Mixtape: A Rare & Forgotten Recording from 1965

The Enigma Machine: How Alan Turing Helped Break the Unbreakable Nazi Code

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.