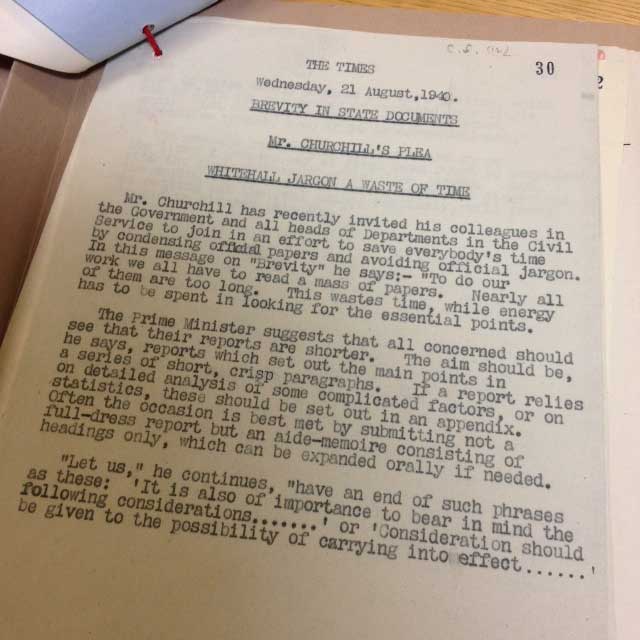

If MasterClass comes calling, you know you’ve made it. In the five years since its launch, the online learning platform has brought on such instructors as Martin Scorsese, Helen Mirren, Steve Martin, Annie Leibovitz, and Malcolm Gladwell, all of whom bring not just knowledge and experience of a craft, but the glow of high-profile success as well. Though MasterClass’ lineup has expanded to include more writers, filmmakers, and performers (as well as chefs, designers, CEOs, and poker players) it’s long been light on visual artists. But it may signal a change that the site has just released a course taught by Jeff Koons, promoted by its trailer as the most original and controversial American artist — as well as the most expensive one.

Just last year, Koons’ sculpture Rabbit set a new record auction price for a work by a living artist: $91.1 million, which breaks the previous record of $58.4 million that happened to be held by another Koons, Balloon Dog (Orange). This came as the culmination of a career that began, writes critic Blake Gopnik, with “taking store-bought vacuum cleaners and presenting them as sculpture,” then creating “full-size replicas of rubber dinghies and aqualungs, cast in Old Master-ish bronze” and later “giant hard-core photos of himself having sex with his wife, the famous Italian porn star known as La Cicciolina (“Chubby Chick”)” and “simulacra of shiny blow-up toys and Christmas ornaments and gems, enlarged to monumental size in gleaming stainless steel.”

With such work, Gopnik argues, Koons has “rewritten all the rules of art — all the traditions and conventions that usually give art order and meaning”; his elevation of kitsch allows us to “see our world, and art, as profoundly other than it usually is.” Not that the artist himself puts it in quite those words. In his well-known manner — “like a space alien who has spent long years studying how to be the perfect, harmless Earthling, but can’t quite get it right” — Koons uses his MasterClass to tell the story of his artistic development, which began in the showroom of his father’s Pennsylvania furniture store and continued into a reverence for the avant-garde in general and Salvador Dalí in particular. From his life he draws lessons on turning everyday objects into art, using size and scale, and living life with “the confidence in yourself to follow your interests.”

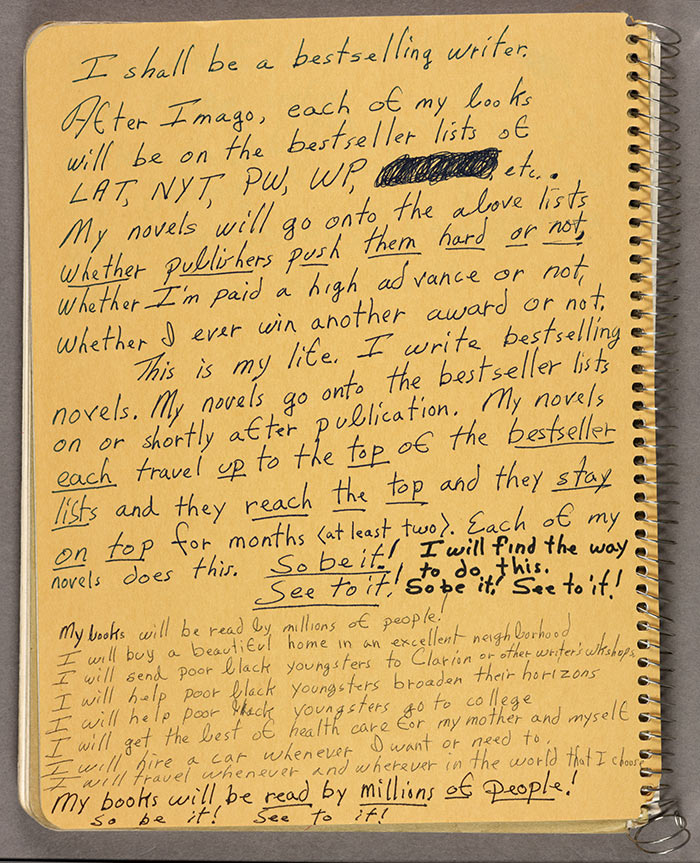

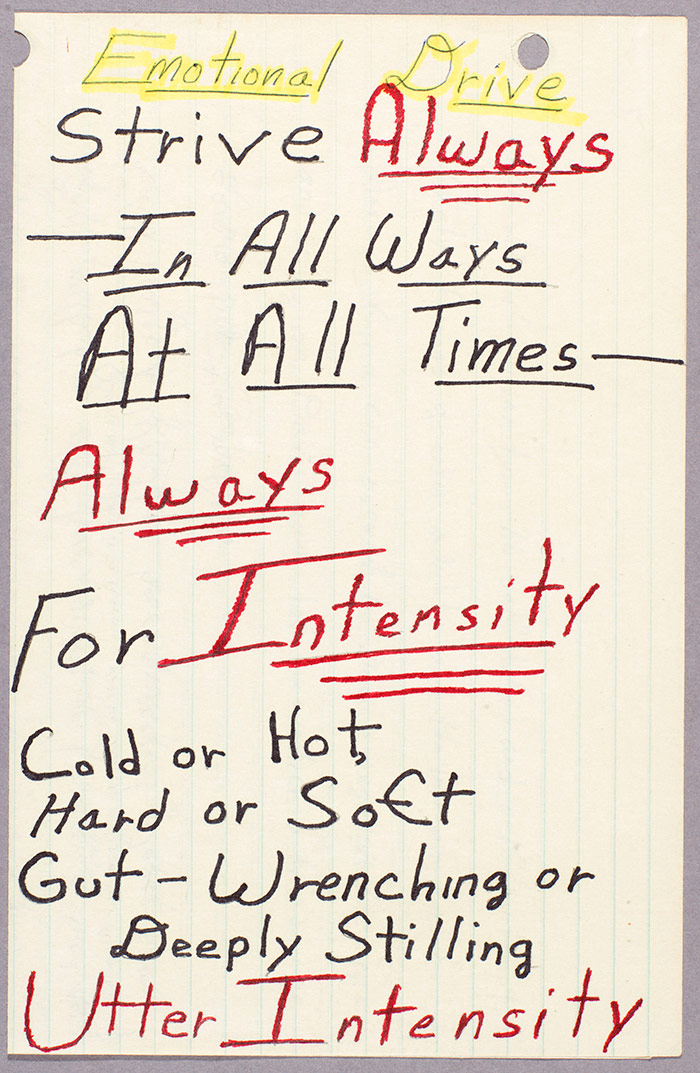

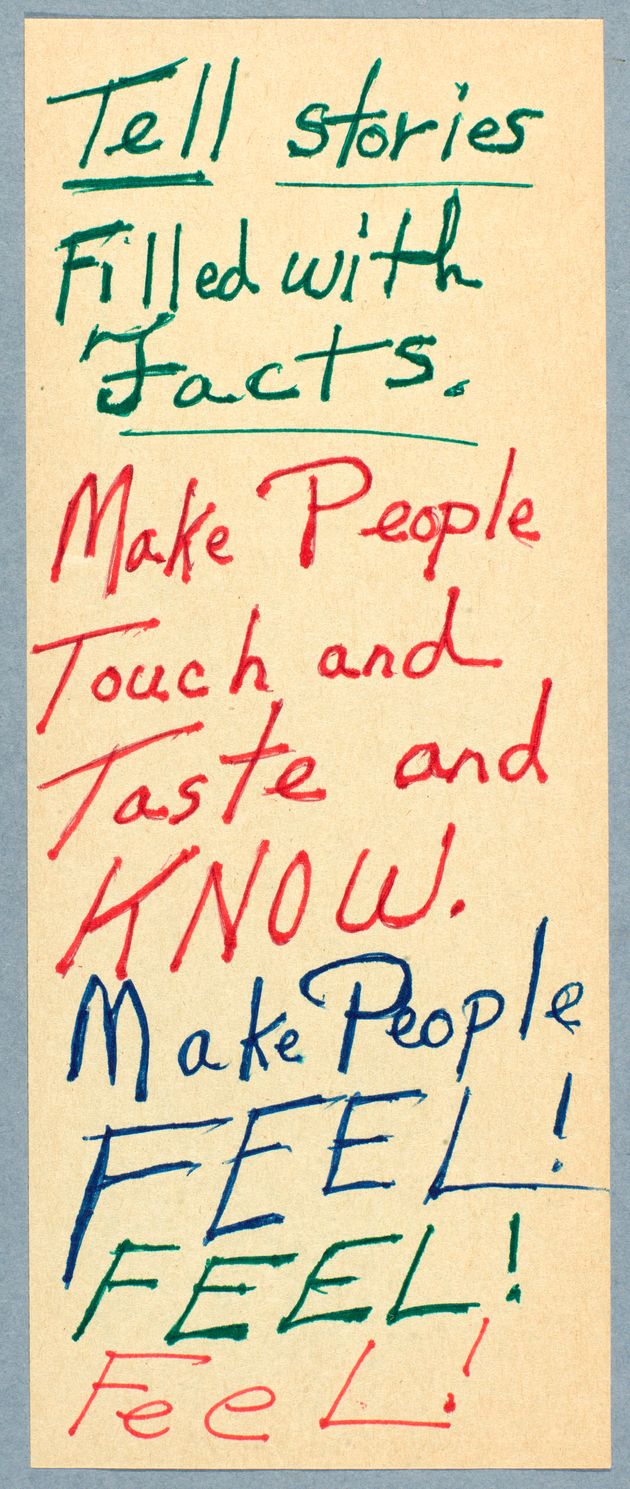

Also new for this holiday season is a MasterClass on storytelling and writing taught by no less renowned a storyteller and writer than Salman Rushdie. The author of Midnight’s Children and The Satanic Verses thus joins on the site a group of novelists as varied as Neil Gaiman, Joyce Carol Oates, Dan Brown, Margaret Atwood, and Judy Blume, but he brings with him a much different body of work and life story. “I’ve been writing, now, for over 50 years,” he says in the course’s trailer just above. “There’s all this stuff about three-act structure, exactly how you must allow a story to unfold. My view is it’s all nonsense.” Indeed, by this point in his celebrated career, Rushdie has narrowed the rules of his craft down to just one: Be interesting.

Easier said than done, of course, which is why Rushdie’s MasterClass comes structured in nineteen practically themed lessons. In these he deals with such lessons as building a story’s structure, opening with powerful lines, drawing from old storytelling traditions, and rewriting — which, he argues, all writing is. To make these fiction-writing concepts concrete, Rushdie offers exercises for you, the student, to work through, and he also takes a critical look back at the failed work he produced in his early twenties. But though his techniques and process have greatly improved since then, his resolve to create, and to do so using his own distinctive sets of interests and experiences, has wavered no less than Koons’. At the moment you can learn from both of them (and MasterClass’ 100+ other instructors) if you take advantage of MasterClass’ holiday 2‑for‑1 deal. For $180, you can buy an annual subscription for yourself, and give one to a friend/family member for free. Sign up here.

Note: If you sign up for a MasterClass course by clicking on the affiliate links in this post, Open Culture will receive a small fee that helps support our operation.

Related Content:

A Short Documentary on Artist Jeff Koons, Narrated by Scarlett Johansson

Hear Salman Rushdie Read Donald Barthelme’s “Concerning the Bodyguard”

Salman Rushdie: Machiavelli’s Bad Rap

Neil Gaiman Teaches the Art of Storytelling in His New Online Course

Margaret Atwood Offers a New Online Class on Creative Writing

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, on Facebook, or on Instagram.