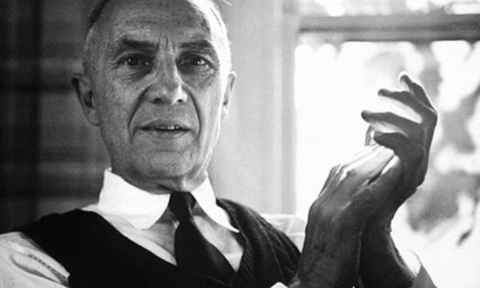

The English logician and philosopher Bertrand Russell was convinced that the religions of the world are not merely untrue, but that they do grievous harm to people. That conviction is very much in evidence in his 1927 speech, “Why I Am Not a Christian,” read here in its complete form by the British actor Terrence Hardiman.

Russell begins by establishing a very general and inclusive definition of the term “Christian.” A Christian, for the purposes of Russell’s argument, is one who believes in God and immortality and also in Christ. “I think you must have at the very lowest a belief that Christ was, if not divine, at least the best and wisest of men,” says Russell. “If you are not going to believe that much about Christ, I do not believe you have any right to call yourself a Christian.”

Beginning with the belief in God, Russell points out the logical fallacies in several of the most popular arguments for the existence of God, starting with the early rational arguments and moving along what he sees as the “intellectual descent” of Christian apologetics to some of the more recent arguments that have “become less respectable intellectually and more and more affected by a kind of moralizing vagueness.” Russell then goes on to explain why Jesus, as depicted in the Gospels, has neither superlative wisdom nor superlative goodness. Although Russell grants Christ “a very high degree of moral goodness,” he asserts that there have been wiser and better men.

The speech was published in 1957 in the book Why I am Not a Christian and Other Essays on Religion and Related Subjects. The text is available online, and you can click here to open it in a new window. This recording will be added to our Free Audio Books collection. Although Russell is addressing the majority religion of his own country, he is equally critical of all religions. He leaves off with these words:

The whole conception of God is a conception derived from the ancient Oriental despotisms. It is a conception quite unworthy of free men. When you hear people in church debasing themselves and saying that they are miserable sinners, and all the rest of it, it seems contemptible and not worthy of self-respecting human beings. We ought to stand up and look the world frankly in the face. We ought to make the best we can of the world, and if it is not so good as we wish, after all it will still be better than what these others have made of it in all these ages. A good world needs knowledge, kindliness, and courage; it does not need a regretful hankering after the past or a fettering of the free intelligence by the words uttered long ago by ignorant men. It needs a fearless outlook and free intelligence. It needs hope for the future, not looking back all the time toward a past that is dead, which we trust will be far surpassed by the future that our intelligence can create.

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. It’s a great way to see our new posts, all bundled in one email, each day.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

Related content:

Face to Face with Bertrand Russell: ‘Love is Wise, Hatred is Foolish’

Bertrand Russell and F.C. Copleston Debate the Existence of God, 1948

Bertrand Russell’s ABC of Relativity: The Classic Introduction to Einstein