“Turkey is a geographical and cultural bridge between the east and the west,” writes Istanbul University’s Gönül Bakay. This was so long before Constantinople became Istanbul, but after the rise of the Ottoman Empire, the region took on a particular significance for Christian Europe. “The Turk” became a threatening and exotic figure in the European imagination, “shaped by a considerable body of literature, stretching from Christopher Marlowe to Thomas Carlyle.” Images of Ottoman Turkey were long drawn from a “mixture of fact, fantasy and fear.”

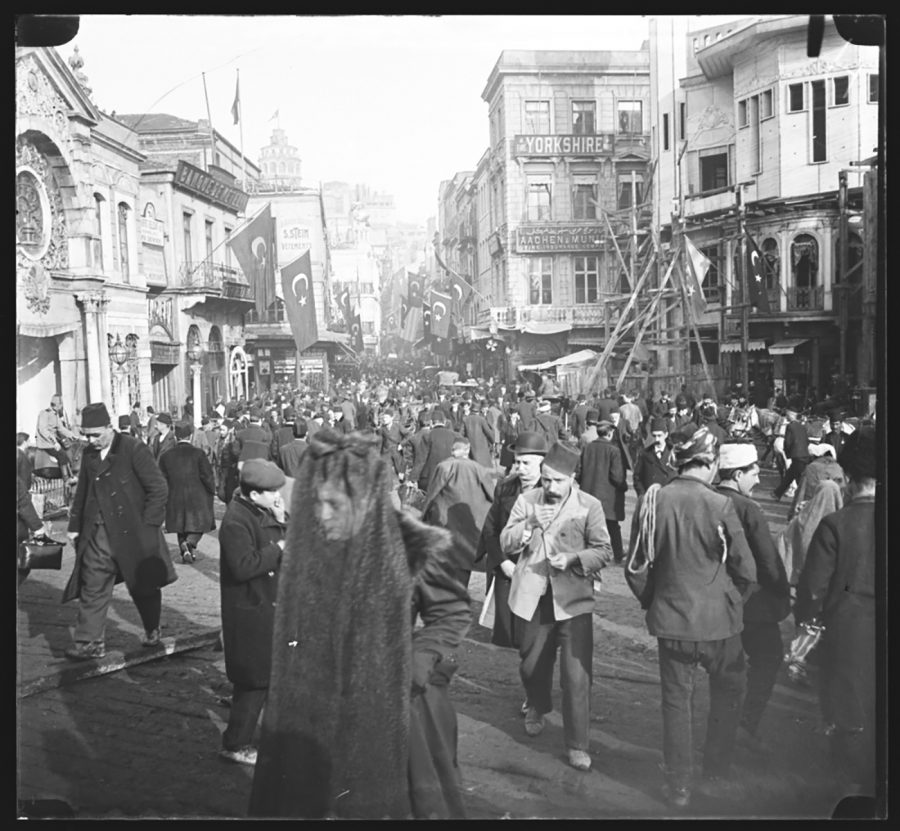

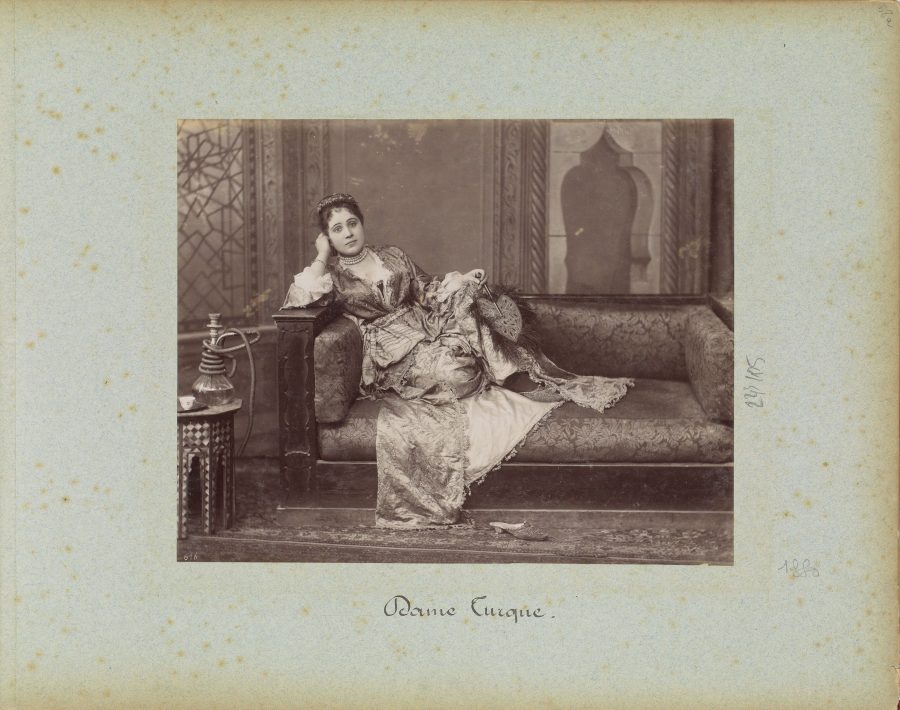

With the advent of photography in the mid-nineteenth century, those images were supplemented, illustrated, and countered by prints depicting Turkish people both in everyday life circumstances and in Orientalist poses.

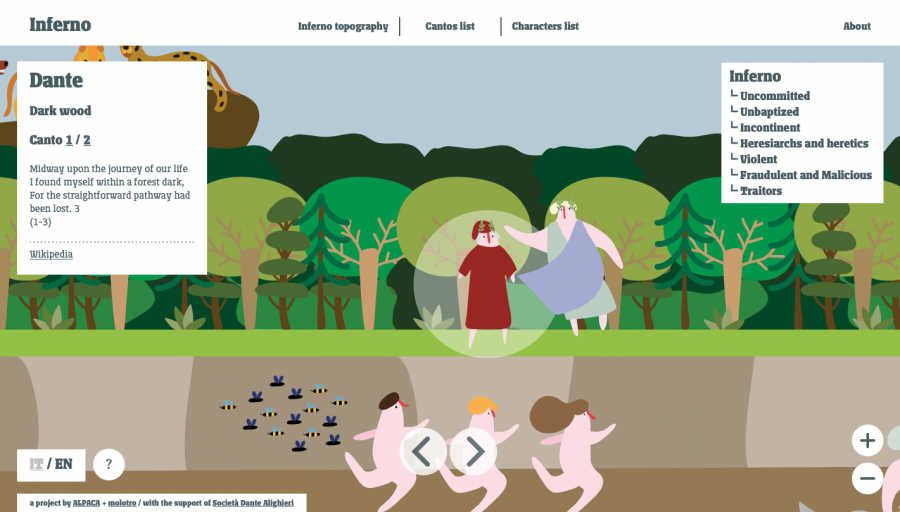

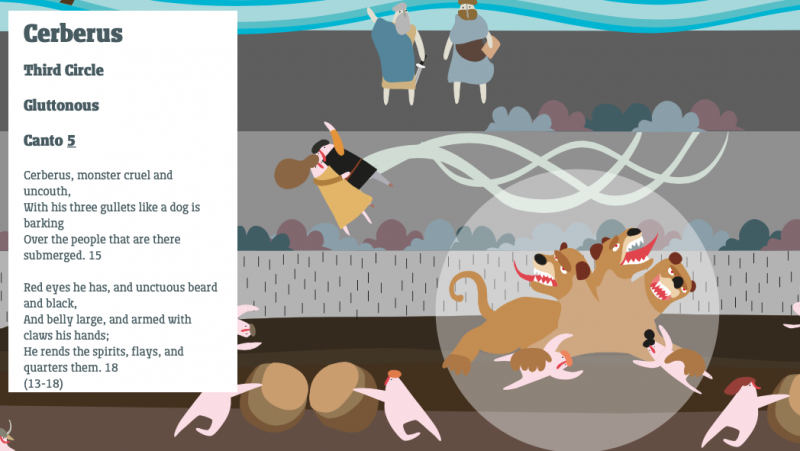

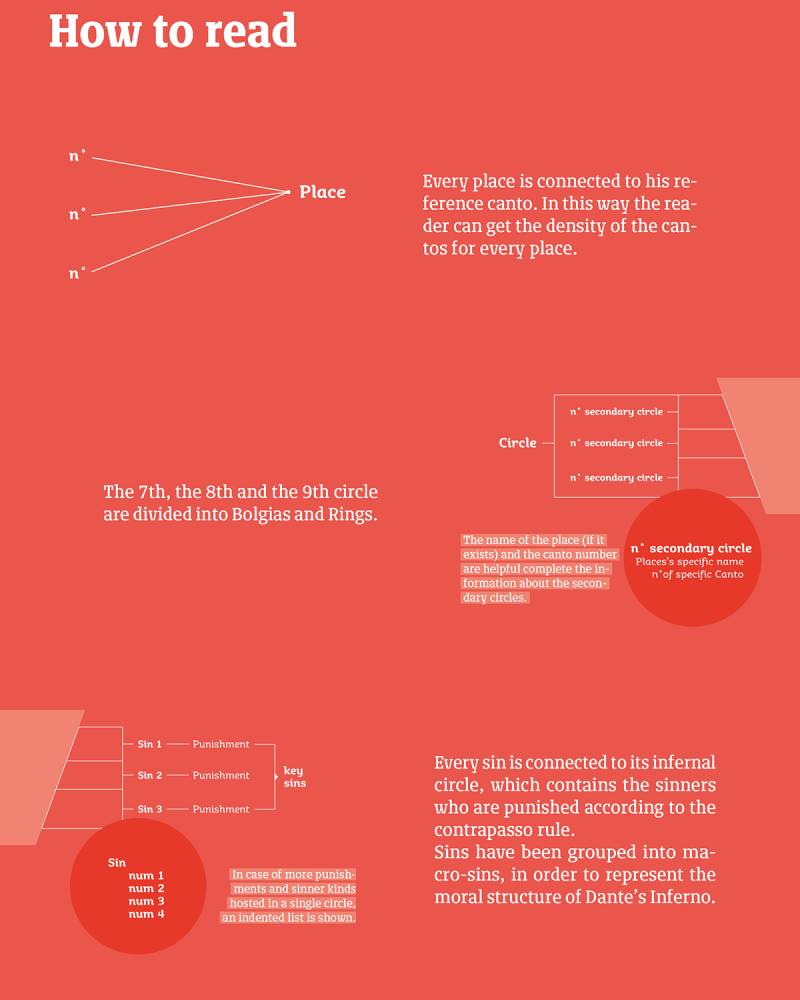

In the final decades of the Ottoman Empire, as modernization took hold all over Europe, viewers might encounter photos of women in poses reminiscent of the Odalisque and street scenes of bustling, cosmopolitan Constantinople, with signs in Ottoman Turkish, English, French, Armenian, and Greek.

Photos of Enver Pasha—de facto ruler of the Ottoman Empire during World War I and “highest-ranking perpetrator of the Armenian genocide,” writes Isotta Poggi at the Getty’s blog—circulated alongside images like that below, a group of Turkish tourists posed near the Sphinx. These and thousands more such photographs of Ottoman Turkey at the turn of the century and into the first years of the Turkish Republic—3,750 digitized images in total—are now available to view and download at the Getty Research Institute.

The photos come from French collector Pierre de Gigord, who acquired them during his many travels through Turkey in the 1980s. They were taken by photographers, some of whose names are lost to history, from all over Europe and the Mediterranean, including Armenian photographers who played a “central role,” notes Poggi, “in shaping Turkey’s national cultural history and collective memory.” (Read artist Hande Sever’s Getty essay on this subject here.) The huge collection contains “landmark architecture, urban and natural landscape, archeological sites of millennia-old civilizations, and the bustling life of the diverse people who lived over 100 years ago.”

Despite the loss of materiality in the transfer to digital, a loss of “formatting, or sense of scale” that changes the way we experience these photos, they “enable us to learn about the past,” writes Poggi, “seeing Turkey’s diverse society” as photography’s early viewers did, and to better understand the present, “observing how certain sites and people, as well as social or political issues, have evolved yet still remain the same.” Enter the Pierre de Gigord collection at the Getty here.

via Hyperallergic/The Getty

Related Content:

New Archive of Middle Eastern Photography Features 9,000 Digitized Images

Tsarist Russia Comes to Life in Vivid Color Photographs Taken Circa 1905–1915

An Online Gallery of Over 900,000 Breathtaking Photos of Historic New York City

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness