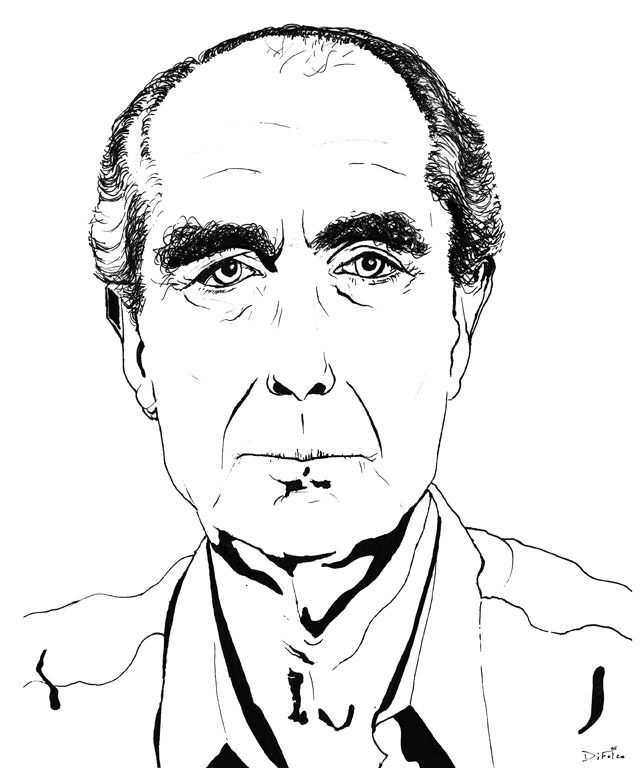

Photo by George F. Landegger, via Wikimedia Commons

F. Scott Fitzgerald started writing in earnest at Princeton University, several of whose literary and cultural societies he joined after enrolling in 1913. So much of his time did he devote to what would become his vocation that he eventually found himself on academic probation. Still, he kept on writing novels even after dropping out and joining the Army in 1917. He wrote hurriedly, with the prospect of being shipped out to the trenches hanging over his head, but that grim fate never arrived. Instead the Army transferred him to Camp Sheridan outside Montgomery, Alabama, at one of whose country clubs young Scott met a certain Zelda Sayre, the “golden girl” of Montgomery society.

With his sights set on marriage, Scott spent several years after the war trying to earn enough money to make a credible proposal. Only the publication of This Side of Paradise, his debut novel about a literarily minded student at Princeton in wartime, convinced Zelda that he could maintain the lifestyle to which she had become accustomed. Between 1921, when they married, and 1948, by which time both had died, F. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald lived an occasionally productive, often miserable, and always intensely compelling life together. The story of this early cultural “power couple” has an important place in American literary history, and Fitzgerald enthusiasts can now use Airbnb to spend the night in the home where one of its chapters played out.

The rentable apartment occupies part of the F. Scott Fitzgerald Museum in Montgomery, an operation run out of the house in which the Fitzgeralds lived in 1931 and 1932. For the increasingly troubled Zelda, those years constituted time in between hospitalizations. She had come from the Swiss sanatorium that diagnosed her with schizophrenia. She would afterward go to Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, where she would write an early version of her only novel Save Me the Waltz, a roman à clef about the Fitzgerald marriage. For Scott’s part, the Montgomery years came in the middle of his work on Tender is the Night, the follow-up to The Great Gatsby for which critics had been waiting since that book’s publication in 1925.

“The house dates to 1910,” writes the Chicago Tribune’s Beth J. Harpaz. “The apartment is furnished in casual 20th century style: sofa, armchairs, decorative lamps, Oriental rug, and pillows embroidered with quotes from Zelda like this one: ‘Those men think I’m purely decorative and they’re fools for not knowing better.’ ” Evocative features include “a record player and jazz albums, a balcony, and flowering magnolia trees in the yard.” It may not offer the kind of space needed to throw a Gatsby-style bacchanal — to the endless relief, no doubt, of the museum staff — but at $150 per night as of this writing, travelers looking to get a little closer to these defining literary icons of the Jazz Age might still consider it a bargain. It also comes with certain modern touches that the Fitzgeralds could hardly have imagined, like wi-fi. But then, given the well-documented tendency toward distraction they already suffered, surely they were better off without it.

You can book your room at Airbnb here.

Related Content:

Free: The Great Gatsby & Other Major Works by F. Scott Fitzgerald

Rare Footage of Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald From the 1920s

Winter Dreams: F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Life Remembered in a Fine Film

The Evolution of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Signature: From 5 Years Old to 21

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.