The chief difficulty for anyone wanting to make an assault on our municipal theatre… is that there can be no question of revealing a mystery. He cannot just point a stumpy finger at the theatre’s ongoings and say, “You may have thought this amounted to something, but let me tell you, it’s a sheer scandal; what you see before you proves your absolute bankruptcy; it’s your own stupidity, your mental laziness and your degeneracy that are being publically exposed.” No, the poor man can’t say that, for it’s no surprise to you; you’ve known it all along; nothing can be done about it.

–Berthold Brecht, “A Reckoning”

Have you ever felt like Network’s Howard Beale? Ranting to anyone who’ll listen about how mad as hell you are? “I don’t have to tell you things are bad. Everybody knows things are bad.”

Or maybe agreed with the weary cynicism of his boss, Max Schumacher? “All of life is reduced to the common rubble of banality.”

Faced with the cruel, stupid theater of mass politics and culture, we begin to feel a blanket of overwhelming futility descend. All of the possible moves have been made and absorbed into the programming—including the outraged critic pointing his finger at the stage.

Avant-garde artists since the late 19th century have correctly sized up this depressing reality. But rather than seize up in fits of rage or succumb to cynicism, they made new forms of theater: Jarry, Dada, Debord, Artaud, Brecht—all had designs to disrupt the oppressive banality of modern stage- and state-craft with mockery, sadism, and shock.

And so too did DEVO, the authors of “Whip It.”

Their 80s New Wave antics seemed like a juvenile art-school prank. Behind it lay theoretical sophistication and serious political intent. “When we first started Devo,” says Mark Mothersbaugh in the “California Inspires Me” video above, “we were artists who were working in a number of different media. We were around for the shootings at Kent State. And it affected us. We were thinking, like, ‘What are we observing?’ And we decided we weren’t observing evolution, we were observing de-evolution.”

Wondering how to change things, the band looked to Madison Avenue for inspiration—intent on taking the techniques of mass persuasion to subvert the enchantments of mass persuasion, “reporting the good news of De-Evolution” in a joyous theater of mockery. The philosophy itself evolved over time, first taking shape in 1970 when Mothersbaugh and Gerald Casale met at Kent State. Casale had already coined the term “De-Evolution”; Mothersbaugh introduced him to its mascot, Jocko-Homo, the 1924 creation of anti-evolution fundamentalist pamphleteer B.H. Shadduck.

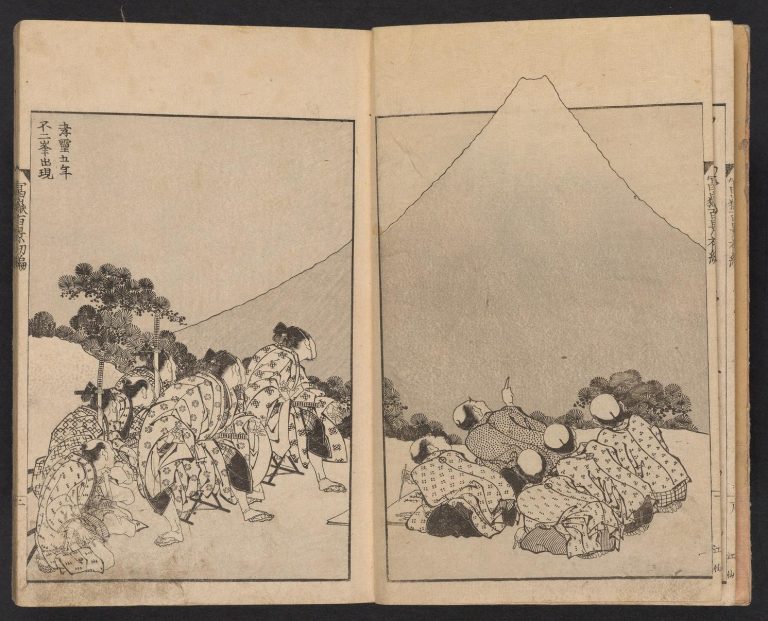

Fascinated by Shadduck’s bizarre, proto-Jack Chick, illustrated freak-outs, Mothersbaugh and his bandmates adopted the character for the first single from their 1978 debut album (top). Are We Not Men? We Are Devo! announced their carnivalesque gospel of human stupidity. Devo proved nothing we didn’t already know. Instead, they showed us the elevation of idiocy to the status of a civil religion. (Later in the 80s, they would expressly parody the national religion with their Evangelical satire DOVE.)

The theater of Devo was weirdly compelling then and is wierdly compelling now, since the banality and casual violence of late-capitalism that threatened to swallow up everything in the twentieth century has, if anything, only become more bloated and grotesque. “As far as Devo was concerned,” writes Ray Padgett at The New Yorker, “Devo wasn’t a band at all but, rather, an art project… inspired by the Dadaists and the Italian Futurists, Devo’s members were also creating satirical visual art, writing treatises, and filming short videos.”

One of those videos, “In the Beginning Was the End: The Truth About De-Evolution,” featured their “first ever cover”—Johnny Rivers’ “Secret Agent Man”—before they re-invented (or “corrected,” as they put it), the Rolling Stones’ “Satisfaction.” They would screen the 9‑minute film, with its footage of two men in monkey masks spanking a housewife, before gigs.

The concepts are aggressively wink-nudge adolescent, reflecting not only Devo’s take on the regressive state of the culture, but also Casale’s belief that “high-school kids know everything already.” But amidst the synths and shiny suits, we still hear Howard Beale’s cri de coeur, “I’m a human being dammit! My life has value!” Only in Devo’s hands it turns to dark comedy—as in the title of a song from their 2010 comeback record Something for Everybody, taken from words printed on the back of a hunter’s safety vest that call back to the band’s beginnings at Kent State: “Don’t Shoot, I’m a Man.”

Related Content:

The Mastermind of Devo, Mark Mothersbaugh, Shows Off His Synthesizer Collection

New Wave Music–DEVO, Talking Heads, Blondie, Elvis Costello–Gets Introduced to America by ABC’s TV Show, 20/20 (1979)

Devo’s Mark Mothersbaugh & Other Arists Tell Their Musical Stories in the Animated Video Series, “California Inspires Me”

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness