The skilled chef has always held a place of honor amongst gourmands and the fine dining elite. But it took television to bring us the celebrity chef: Julia Childs and Jacques Pepin; Dom DeLuise and Paul Prudhomme. Those were the good old days, before reality TV turned cooking into a competitive sport. Still, we’ve got many quality cooks on the tube, entertaining and hugely informative: Alton Brown, Anthony Bourdain, Gordon Ramsay, Jamie Oliver…. Many of us who take cooking seriously have at one time or another apprenticed under one of these food gurus.

My personal favorite? Well, I’m a fan of haute cuisine as fashioned by Salvador Dalí. Sure, the surrealist painter and all-around weirdo has been dead since 1989, and never had anything approaching a cooking show in his lifetime (though he did make a few TV ads and an appearance on What’s My Line?). Nor is Dalí known for his cooking. As you might guess, there’s good reason for that.

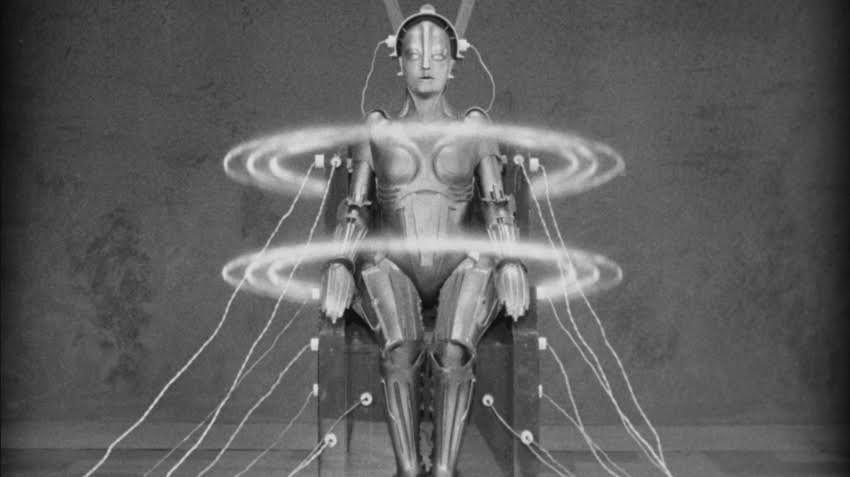

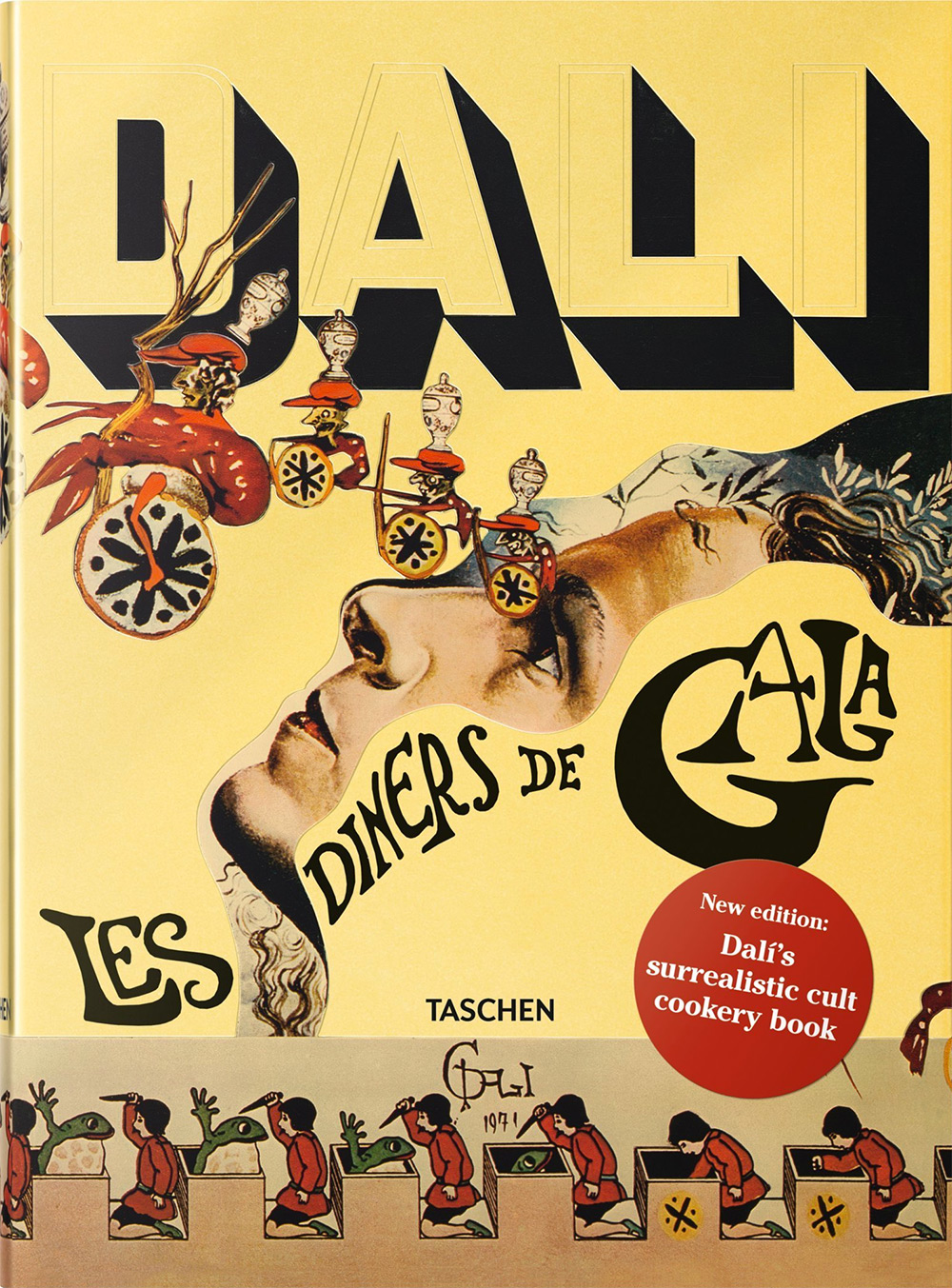

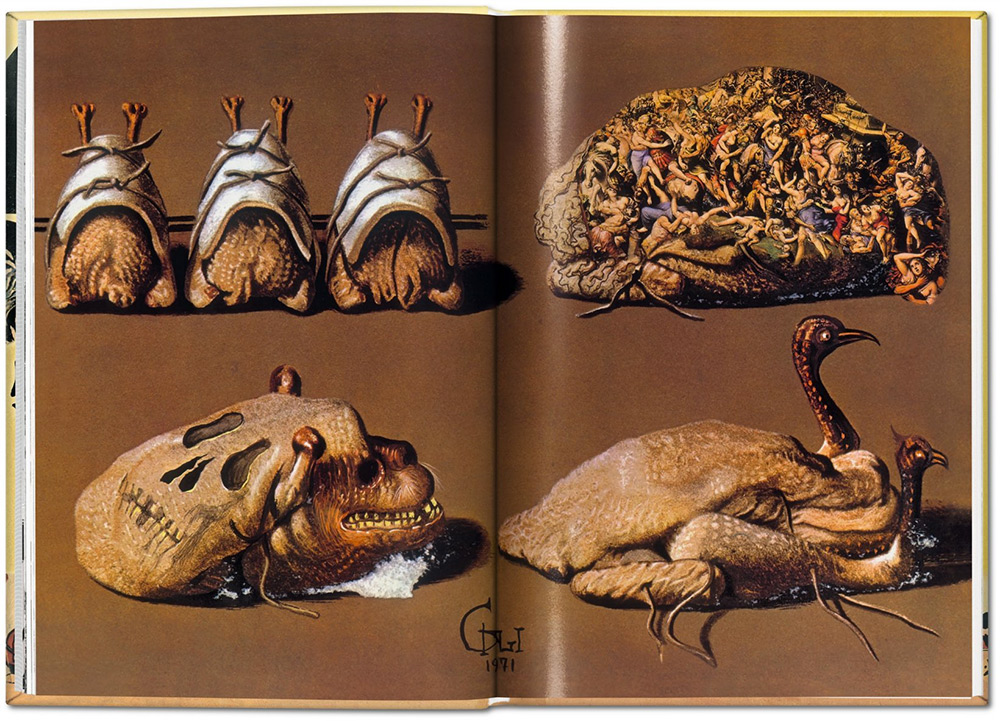

Dishes like “Veal Cutlets Stuffed with Snails,” “Thousand Year Old Eggs,” and “Toffee with Pine Cones” were never going to catch on widely. But when it comes to food as art—as an especially strange and imaginative form of art—it’s hard to beat Dalí’s rare, legendary 1973 cookbook Les Diners de Gala, just reissued by Taschen.

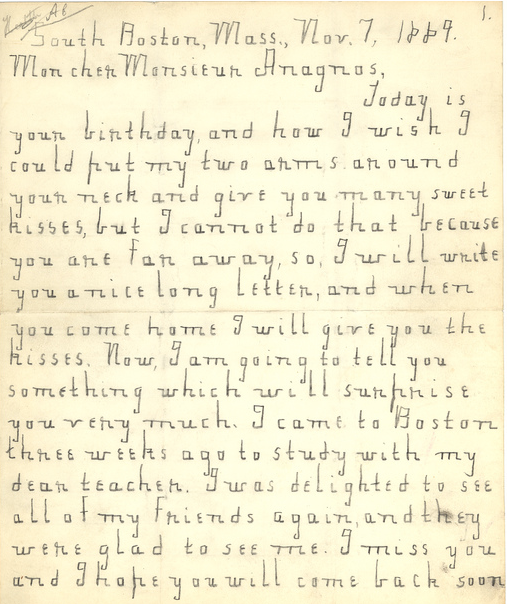

The book, writes This is Colossal, represented “a dream fulfilled” for Dalí, “who claimed at the age of 6 that he wanted to be a chef.” As is sometimes the case when a life’s goal goes unmet—it is perhaps for the best that the Spanish painter never seriously attempted to interest the general public in his sometimes inedible concoctions. He did, however, entertain his coterie of admirers, friends, and celebrity acquaintances with “opulent dinner parties thrown with his wife Gala.” As the cookbook suggests, these events “were almost more theatrical than gustatory.” In addition to the bizarre dishes he and Gala prepared, the guests “were required to wear completely outlandish costumes and an accompaniment of wild animals often roamed free around the table”…..

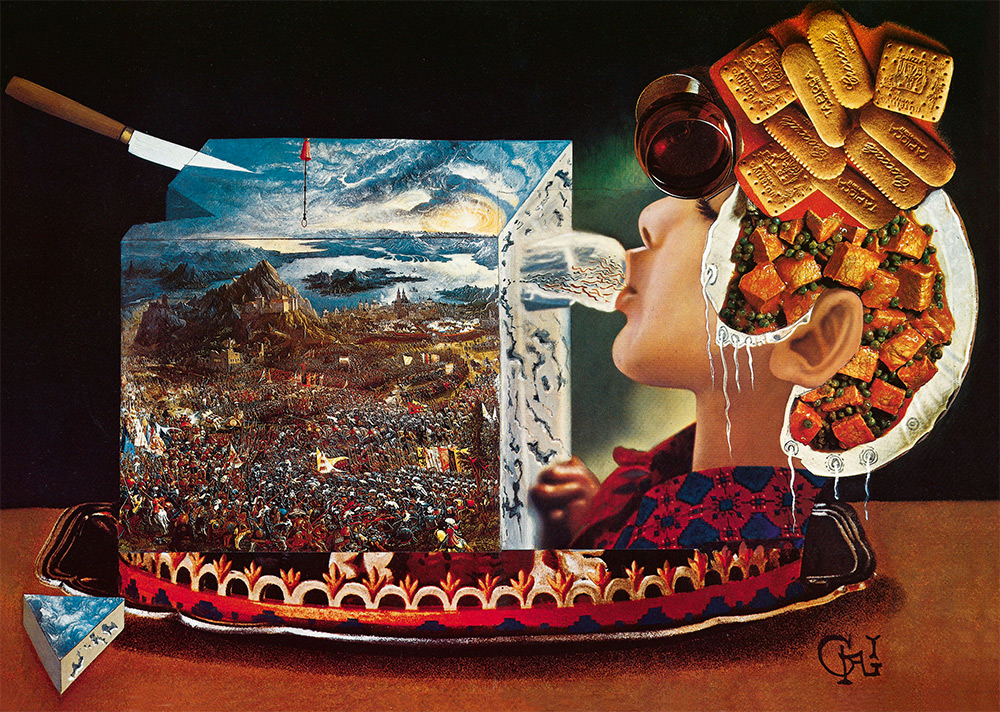

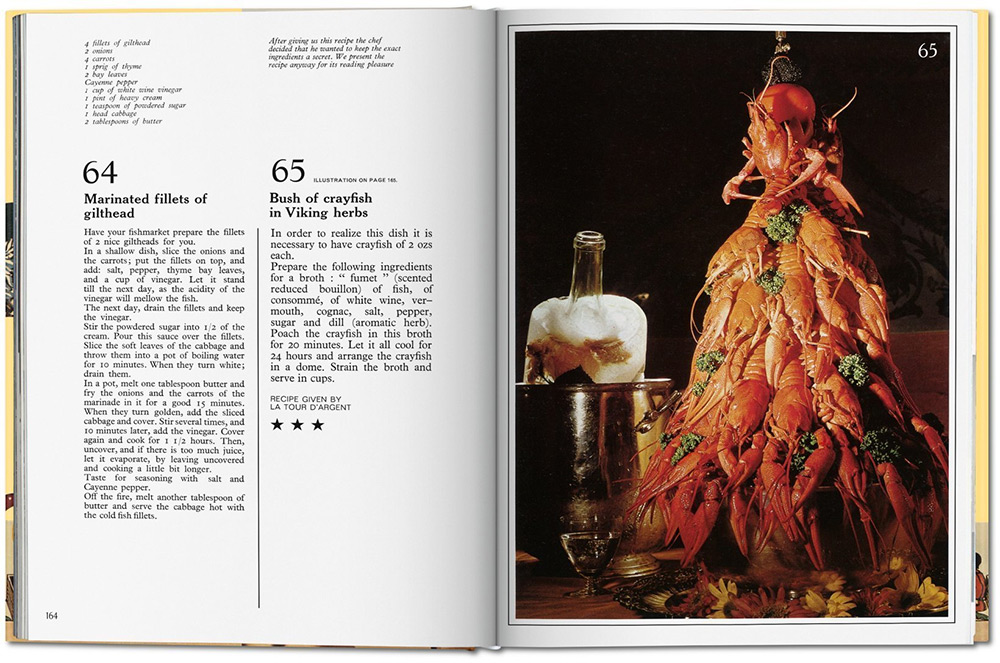

If only Dalí had lived into the age of the Kardashians. Likely he would have leapt at the chance to turn these art parties into great TV. Or maybe not. In any case, we can now reconstruct them ourselves with what design site It’s Nice That calls “a delicious combination of elaborately detailed oil paintings and kitsch 1970s food photography.” Along the way, Dalí drops aphorisms like “the jaw is our best tool to grasp philosophical knowledge” (recalling Nietzsche’s preoccupation with digestion). And despite the absurdity of many of these dishes—and paintings like that above which make the turducken look like casual fare—many of the actual recipes, This is Colossal notes, “originated in some of the top restaurants in Paris at the time including Lasserre, La Tour d’Argent, Maxim’s, and Le Train Bleu.”

However, even as far back as 1973, home cooks had begun to fret about the healthiness of their food. Dalí gives such people fair warning; Les Diners de Gala, he writes, “is uniquely devoted to the pleasures of Taste. Don’t look for dietetic formulas here.”

We intend to ignore those charts and tables in which chemistry takes the place of gastronomy. If you are a disciple of one of those calorie-counters who turn the joys of eating into a form of punishment, close this book at once; it is too lively, too aggressive, and far too impertinent for you.

As if you thought Dalí would bow to something as quotidian as nutrition. See many more surreally sensual food illustrations and quotes from the book at Brain Pickings, where you’ll also find the full, extravagant recipe for “Conger of the Rising Sun.” You can order Les Diners de Gala online.

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. It’s a great way to see our new posts, all bundled in one email, each day.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

Related Content:

Salvador Dalí Takes His Anteater for a Stroll in Paris, 1969

Salvador Dalí Goes Commercial: Three Strange Television Ads

Salvador Dalí’s Melting Clocks Painted on a Latte

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness