“For average prospective house owners the choice between the hysterics who hope to solve housing problems by magic alone and those who attempt to ride into the future piggy back on the status quo, the situation is confusing and discouraging.” Those words, as much as they could describe the situation today, actually came printed in Arts & Architecture magazine’s issue of June 1945.

“Therefore it occurs to us that the only way in which any of us can find out anything will be to pose specific problems in a specific program on a put-up-or-shut-up basis.” What the magazine, at the behest of its publisher John Entenza, put up was the Case Study Houses, which defined the ideal of the midcentury modern American home.

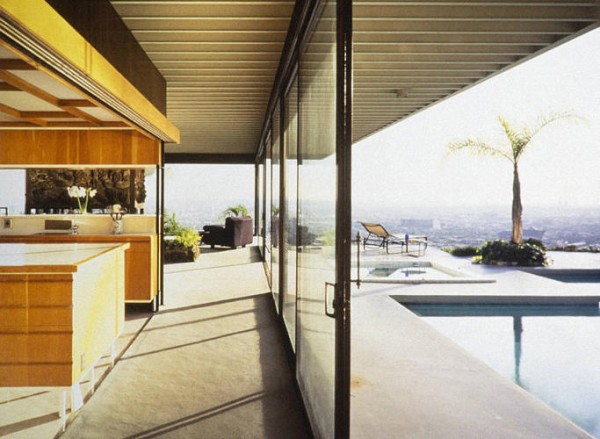

More specifically, they defined the ideal of the midcentury modern southern Californian home. Los Angeles provided a promising environment for many of the formidable European minds who came to America around the Second World War, including writers like Aldous Huxley, composers like Arnold Schoenberg, and philosophers like Theodor Adorno. Architects, such as the earlier arrival Richard Neutra, especially thrived in the young city’s vast space and under its bright sun, giving shape to a new kind of twentieth-century house, one influenced by the rigorously clean aesthetics of the German Bauhaus movement but adapted to a much friendlier climate, both in terms of the weather and the freedom from strict tradition.

Even if you don’t know architecture, you know the Case Study houses from their countless appearances in movies, television, and print over the past seventy years. Sooner or later, everyone sees an image of Neutra’s Stuart Bailey House, Charles and Ray Eames’ Eames House, or Pierre Koenig’s Stahl House. The decades have turned these and other houses from the peak of midcentury modernism into priceless architectural treasures — or at least extremely high-priced architectural treasures. Some open themselves to tours now and again, but very few of us will ever have a chance to experience these houses as not quasi-museums but actual livable spaces.

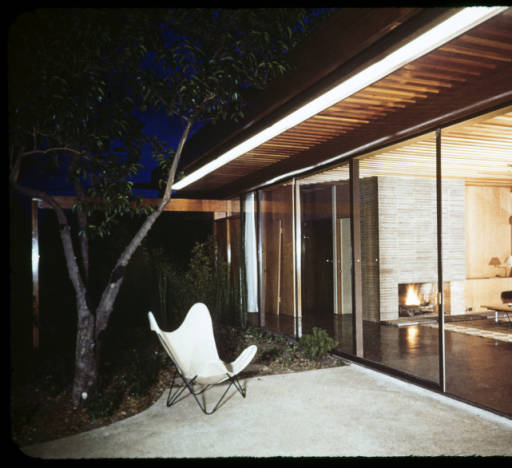

Now we have the next best thing in the form of the University of Southern California’s Architectural Teaching Slide Collection, which collects about 1300 rarely seen photographs of midcentury modern houses shot all over the western United States from the 1940s to the 1960s by Koenig himself, along with his colleague Fritz Block, who also happened to own a color slide company. “Instead of the polished tableaus you might find in the pages of Architectural Digest,” writes Hyperallergic’s Carey Dunne, “these spontaneous snapshots capture quirky and more intimate views.” Koenig and Block captured these houses “with an architect’s geometrically minded and detail-oriented eye, never presenting them as mere real estate.” The archive also offers images of models, blueprints, and other such technical materials.

Arts & Architecture meant to commission ideas for the everyman’s house of the future, “subject to the usual (and sometimes regrettable) building restrictions,” “capable of duplication,” and “in no sense… an individual ‘performance.’ ” Yet American midcentury modern houses, from the Case Study Program or elsewhere, all came out as individual performances, but also the first works of architecture many of us get to know as works of art. And the work of architectural photographers like Julius Shulman, especially his iconic shot of the Stahl House high above the illuminated grid of Los Angeles, has done much to instill in viewers a reverence suited to art. A collection of non-standard views like these, though, reminds us that even the most visionary house is a real place. Enter the USC archive here.

All Images: via USC Digital Library

via Hyperallergic/Fast Co Design

Related Content:

A Quick Animated Tour of Iconic Modernist Houses

Bauhaus, Modernism & Other Design Movements Explained by New Animated Video Series

Gehry’s Vision for Architecture

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and style. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer, the video series The City in Cinema, the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future?, and the Los Angeles Review of Books’ Korea Blog. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.