They’re all selected and animated by Simon Appel. Be warned, the voice of the narrator is not exactly Churchillian.

You can find a longer selection of Churchill’s greatest quotes over at Townhall.…

They’re all selected and animated by Simon Appel. Be warned, the voice of the narrator is not exactly Churchillian.

You can find a longer selection of Churchill’s greatest quotes over at Townhall.…

Along with toppling democratically elected governments, funneling money illegally to dubious political groups and producing pornographic movies about heads of state, the Central Intelligence Agency has also been fiendishly good at manipulating language. After all, this is the organization that made “waterboarding” seem much more acceptable, at least to the Washington elite, by rebranding it as “enhanced interrogation techniques.” Another CIA turn of phrase, “extraordinary rendition,” sounds so much better to the ear than “illegal kidnapping and torture.”

Not too long ago, the CIA’s style guide, called the Style Manual and Writers Guide for Intelligence Publications, was posted online. “Good intelligence depends in large measure on clear, concise writing,” writes Fran Moore, Director of Intelligence in the foreword. And considering the agency’s deftness with the written word, it shouldn’t come as a surprise that it’s remarkably good. Some highlights:

And then there are some rules that will remind you this guide is the product of a particularly shadowy arm of the U.S. Government.

It’s unclear whether or not the guide is being used for the CIA’s queasily flip, profoundly unfunny Twitter account.

If you’re looking for a more conventional style guide, remember that Strunk & White’s Elements of Style is also online.

Related Content:

How to Spot a Communist Using Literary Criticism: A 1955 Manual from the U.S. Military

How the CIA Secretly Funded Abstract Expressionism During the Cold War

Donald Duck’s Bad Nazi Dream and Four Other Disney Propaganda Cartoons from World War II

Jonathan Crow is a Los Angeles-based writer and filmmaker whose work has appeared in Yahoo!, The Hollywood Reporter, and other publications. You can follow him at @jonccrow.

Before he directed such mind-bending masterpieces as Time Bandits, Brazil and Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, before he became short-hand for a filmmaker cursed with cosmically bad luck, before he became the sole American member of seminal British comedy group Monty Python, Terry Gilliam made a name for himself creating odd animated bits for the UK series Do Not Adjust Your Set. Gilliam preferred cut-out animation, which involved pushing bits of paper in front of a camera instead of photographing pre-drawn cels. The process allows for more spontaneity than traditional animation along with being comparatively cheaper and easier to do.

Gilliam also preferred to use old photographs and illustrations to create sketches that were surreal and hilarious. Think Max Ernst meets Mad Magazine. For Monty Python’s Flying Circus, he created some of the most memorable moments of a show chock full of memorable moments: A pram that devours old ladies, a massive cat that menaces London, and a mustached police officer who pulls open his shirt to reveal the chest of a shapely woman. He also created the show’s most iconic image, that giant foot during the title sequence.

On Bob Godfrey’s series Do It Yourself Film Animation Show, Gilliam delved into the nuts and bolts of his technique. You can watch it above. Along the way, he sums up his thoughts on the medium:

The whole point of animation to me is to tell a story, make a joke, express an idea. The technique itself doesn’t really matter. Whatever works is the thing to use. That’s why I use cut-out. It’s the easiest form of animation I know.

He also notes that the key to cut-out animation is to know its limitations. Graceful, elegant movement à la Walt Disney is damned near impossible. Swift, sudden movements, on the other hand, are much simpler. That’s why there are far more beheadings in his segments than ballroom dancing. Watch the whole clip. If you are a hardcore Python enthusiast, as I am, it is pleasure to watch him work. Below find one of his first animated movies, Storytime, which includes, among other things, the tale of Don the Cockroach. Also don’t miss, this video featuring All of Terry Gilliam’s Monty Python Animations in a Row.

Related Content:

The Best Animated Films of All Time, According to Terry Gilliam

Terry Gilliam: The Difference Between Kubrick (Great Filmmaker) and Spielberg (Less So)

The Miracle of Flight, the Classic Early Animation by Terry Gilliam

Jonathan Crow is a Los Angeles-based writer and filmmaker whose work has appeared in Yahoo!, The Hollywood Reporter, and other publications. You can follow him at @jonccrow.

A couple weeks back, we mentioned that Brian Knappenberger had released his new documentary about Aaron Swartz, The Internet’s Own Boy, under a Creative Commons license, making it free to watch online. He now returns with a short op-doc for The New York Times. It’s called A Threat to Internet Freedom, and it explains why preserving Net neutrality remains “critically important for the future of Internet freedom and access.” It you’re getting up to speed on the whole net neutrality question, you’ll perhaps want to pair this video with Michael Goodwin’s new illustrated primer, Vi Hart’s doodle-filled introduction or John Oliver’s comedic but not less substantive take on the matter.

via BoingBoing

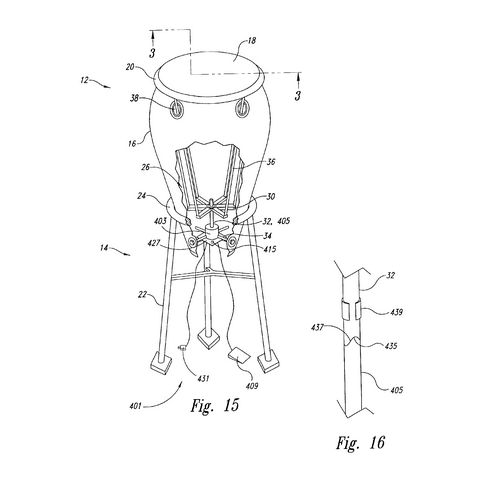

Maybe you knew about Marcel Duchamp’s passion for chess. But did you know about Marlon Brando’s passion for conga drums? Longtime fans may have first picked up on it in 1955, when the actor gave a microwave-link television tour of his Hollywood Hills home to Edward R. Murrow on Person to Person. Halfway through the segment (above), Brando gets into his history with the instrument, and even offers to “run downstairs and give you a lick or two” — and the always highly-prepared program had cameras in the conga room ready to capture this “impromptu” performance. While the interests actors keep on the side may tend to wane, Brando’s seems to have waxed, and later in life he even, writes Movieline’s Jen Yamato, “enlisted the help of Latin jazz percussionist Poncho Sanchez while developing a new tuning system for conga drums.” We can behold the extent and seriousness of Brando’s pursuit of conga perfection with a look at one of those patents, filed in 2002, for an automatic “drumhead tensioning device and method.”

As The Atlantic’s Rebecca Greenfield explains in a post on “Patents of the Rich and Famous,” “tightening a drum takes a lot of effort. Once the drum head loses its tension, there are typically six separate rods that need tightening. Far too many rods for Marlon. Brando explains that others have tried to develop mechanisms that would improve the drum tightening experience but none of them provided a simple or affordable solution.” Hence his motorized “simple and inexpensive drum tuning device that is also accurate and reliable and not subject to inadvertent adjustments.” And if you have no need for an automatic conga drum tuner, perhaps we can interest you in another of Brando’s achievements? “He had these shoes that you can wear in the pool, that would increase friction as you walk on the bottom of the pool to give you a better workout,” says patent attorney Kevin Costanza in an NPR story on Brando’s inventions. Or maybe you’d prefer to simply watch The Godfather again.

Related Content:

Marlon Brando Screen Tests for Rebel Without A Cause (1947)

The Godfather Without Brando?: It Almost Happened

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture and writes essays on cities, language, Asia, and men’s style. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Sci-fi author B.C. Kowalski recently posted a short essay on why the advice to write every day is, for lack of a suitable euphemism, “bullshit.” Not that there’s anything wrong with it, Kowalski maintains. Only that it’s not the only way. It’s said Thackeray wrote every morning at dawn. Jack Kerouac wrote (and drank) in binges. Every writer finds some method in-between. The point is to “do what works for you” and to “experiment.” Kowalski might have added a third term: diversify. It’s worked for so many famous writers after all. James Joyce had his music, Sylvia Plath her art, Hemingway his machismo. Faulkner drew cartoons, as did his fellow Southern writer Flannery O’Connor, his equal, I’d say, in the art of the American grotesque. Through both writers ran a deep vein of pessimistic humor, oblique, but detectable, even in scenes of highest pathos.

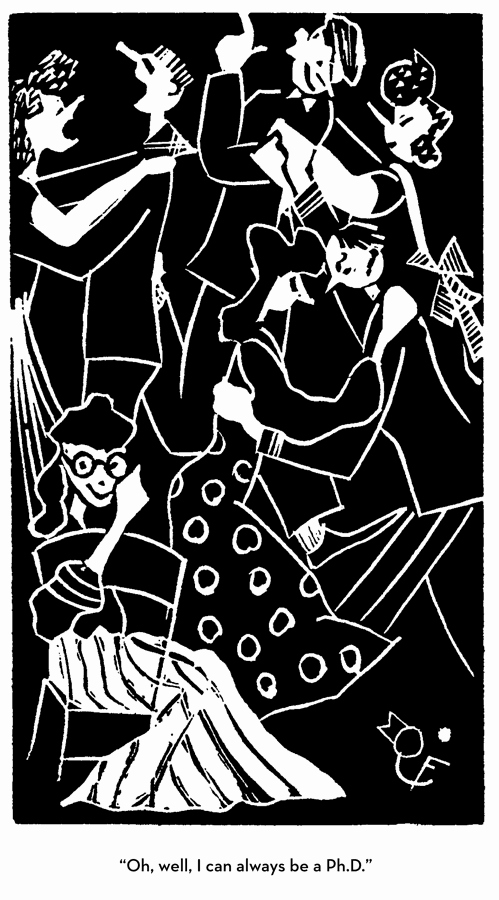

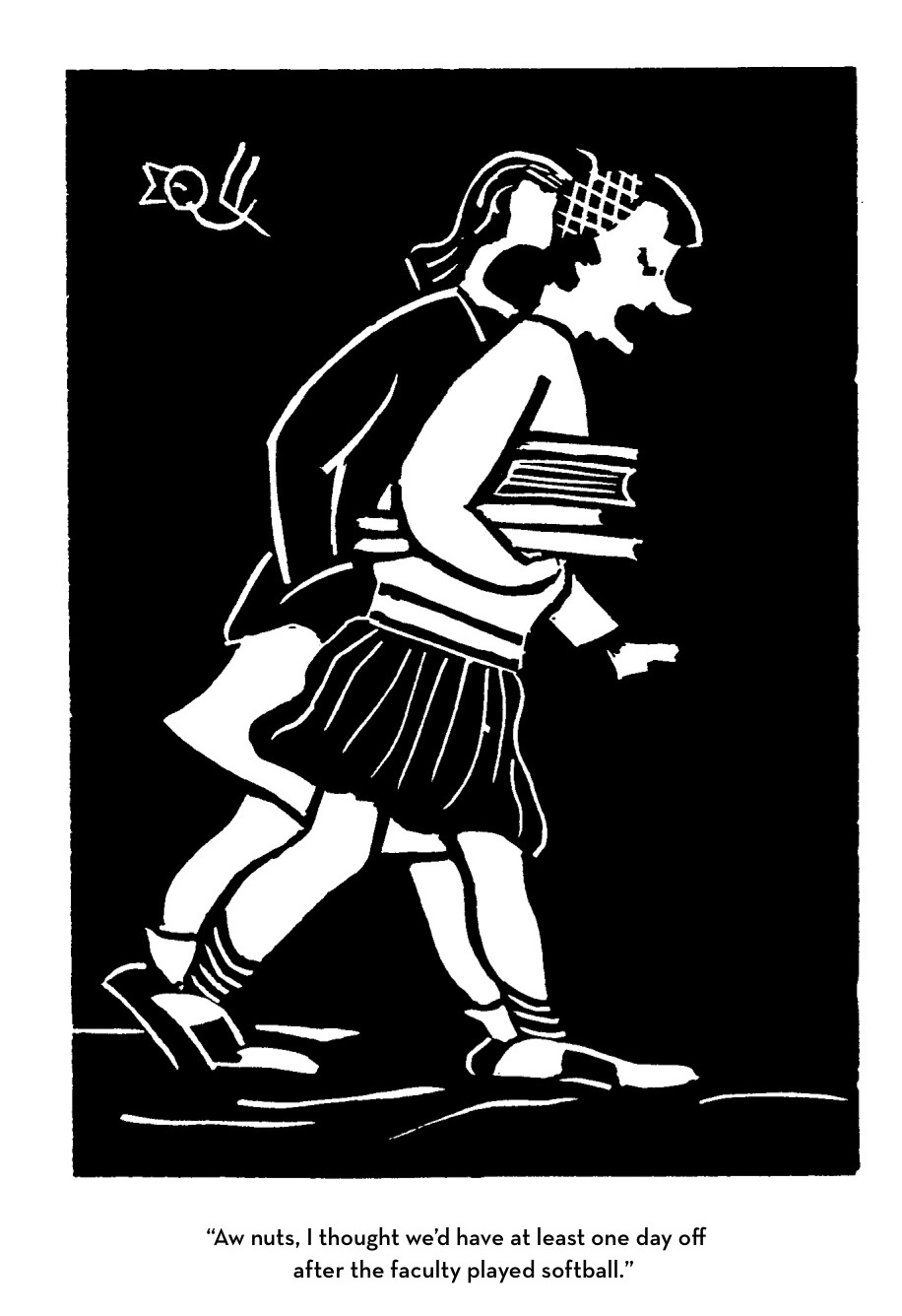

O’Connor’s visual work, writes Kelly Gerald in The Paris Review, was a “way of seeing she described as part of the ‘habit of art’”—a way to train her fiction writer’s eye. Her cartoons hew closely to her authorial voice: a lone sardonic observer, supremely confident in her assessments of human weakness. Perhaps a better comparison than Faulkner is with British poet and doodler Stevie Smith, whose bleak vision and razor-sharp wit similarly cut through mountains of… shall we say, bullshit. In both pen & ink and linoleum cuts, O’Connor set deadpan one-liners against images of pretension, conformity, and the banality of college life. In the cartoon at the top, she seems to mock the pursuit of credentials as a refuge for the socially disaffected. Above, a campaigner for a low-level office deploys bombastic pseudo-Leninist rhetoric, and in the cartoon below, a cranky character escapes a horde of identical WAVES.

O’Connor was an intensely visual writer with, Gerald writes, a “natural proclivity for capturing the humorous character of real people and concrete situations,” fully credible even at their most extreme (as in the increasingly horrific self-lacerations of Wise Blood’s Hazel Motes). She began drawing at five and produced small books and sketches as a child, eventually publishing cartoons in almost every issue of her high-school and college’s newspapers and yearbooks. Her alma mater Georgia College, then known as Georgia State College for Women, has published a book featuring her cartoons from her undergraduate years, 1942–45.

More recently, Gerald edited a collection called Flannery O’Connor: The Cartoons for Fantagraphics. In his introduction, artist Barry Moser describes in detail the technique of her linoleum cuts, calling them “coarse in technical terms.” And yet, “her rudimentary handling of the medium notwithstanding, O’Connor’s prints offer glimpses into the work of the writer she would become” with their “little O’Connor petards aimed at the walls of pretentiousness, academics, student politics, and student committees.” Had O’Connor continued making cartoons into her publishing years, she might have, like B.C. Kowalski, aimed one of those petards at those who dispense dogmatic, cookie-cutter writing advice as well.

Related Content:

The Art of William Faulkner: Drawings from 1916–1925

The Art of Sylvia Plath: Revisit Her Sketches, Self-Portraits, Drawings & Illustrated Letters

The Art of Franz Kafka: Drawings from 1907–1917

Rare 1959 Audio: Flannery O’Connor Reads ‘A Good Man is Hard to Find’

Flannery O’Connor: Friends Don’t Let Friends Read Ayn Rand (1960)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Maybe you’re a diehard Game of Thrones fan. Maybe you’re not. Either way, you’ll marvel at this behind-the-scenes video. The short clip was put together by Mackevision, one of the VFX (visual effects) studios that worked on Season 4 of the HBO series. As one commenter on Metafilter noted, “The obvious stuff, such as castles in the background, is expected. As is adding in extra troops. But adding the fog, bits of vines and changing the color of the grass are the little touches that enliven a scene. Love they’re making mountains just pop in the background to illustrate the VFX work.” Another commenter noted, “It feels like a modern-day Python animation.” All I can say is that we’ll have more on that later today.

Related Content:

Animated Video Explores the Invented Languages of Lord of the Rings, Game of Thrones & Star Trek

15-Year-Old George R.R. Martin Writes a Fan Letter to Stan Lee & Jack Kirby (1963)

Revealed: The Visual Effects Behind The Great Gatsby

In 1963, the Pantone corporation began publishing a bi-yearly color guide, which divides and categorizes every color under the sun. The astonishingly ubiquitous guide is an essential tool for designers of every stripe, from a fashion guru figuring out what color to highlight in her fall line to the guy in charge of creating a color palette for the interior of a new Boeing-787.

Twice a year, Pantone, along with a shadowy cabal of colorists from around the world, meet in a European city and, with the secrecy of the Vatican choosing a new pope, they select the color of the season.

They are the reason why you painted your kitchen Wasabi Green a couple years ago and why, whether you want to or not, you’ll be wearing Radiant Orchid next year. Slate did a great write up about the whole confusing process a while back.

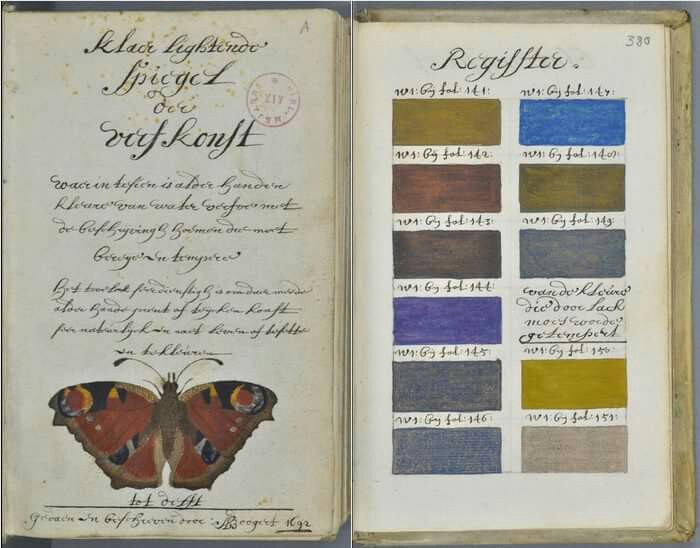

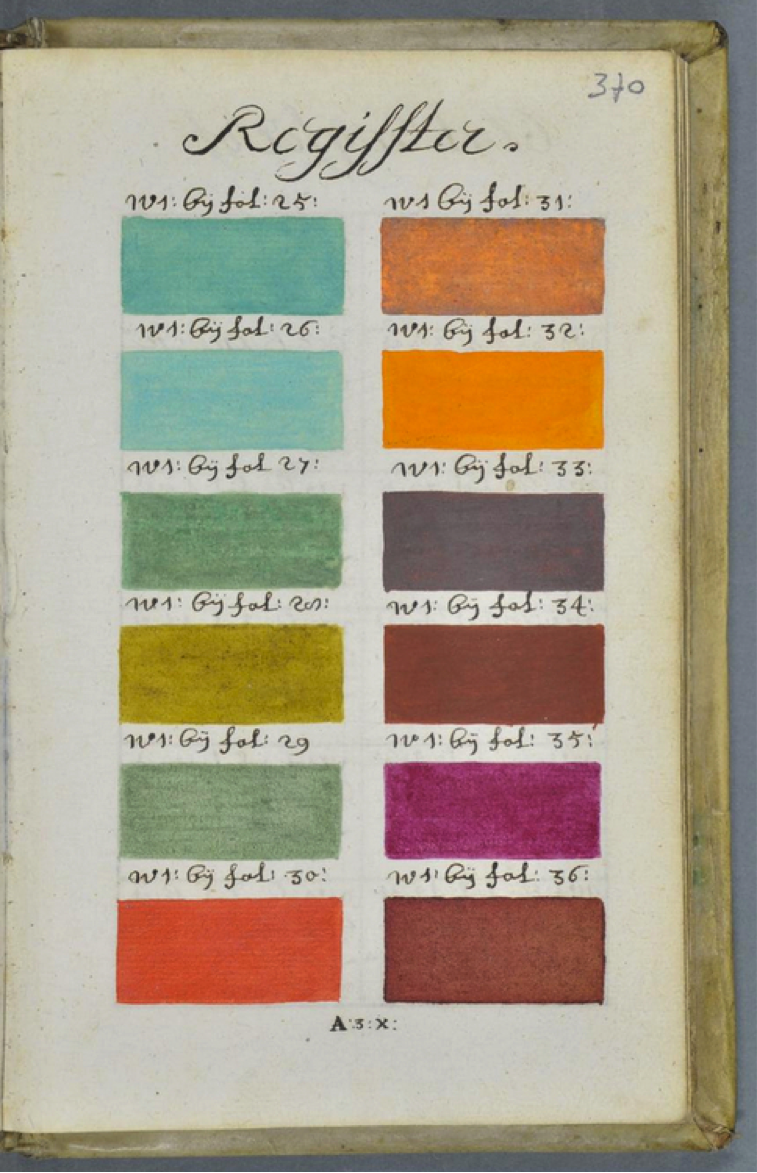

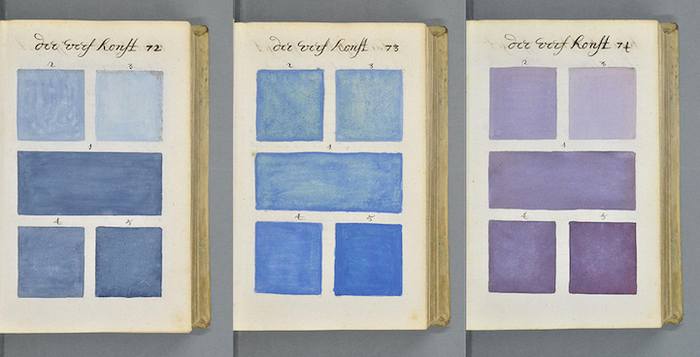

Over 250 years before the Color-Industrial Complex reared its head, a mysterious Dutch artist also detailed every color in the spectrum, only he did it all by hand. Known by the snicker-inducing name of A. Boogert, the author set out to demonstrate how to mix watercolor paint and how to manipulate the paint’s value by adding water. Yet he approached his task with a staggering level of detail and depth; the resulting book — Traité des couleurs servant à la peinture à l’eau — is over 700 pages. It’s about as thorough a color guide as one could imagine in a world without color printers.

The book was largely forgotten, gathering dust at the Bibliothèque Méjanes in Aix-en-Provence, France until Dutch art historian Erik Kwakkel, who translated the introduction, posted selections from the book on his blog. Herr Boogert apparently intended the book to be educational for aspiring artists. Unfortunately, only a few artists at the time ever got a chance to see the one-of-a-kind book.

You can see scans of the book above. And if you want to more, click here to see them in high resolution.

For more intriguing manuscripts, be sure to follow Erik Kwakkel’s Tumblr here.

Related Content:

Wassily Kandinsky Caught in the Act of Creation, 1926

When Respected Authors, from Goethe to Henry Miller, Try Their Hand at Painting

Jonathan Crow is a Los Angeles-based writer and filmmaker whose work has appeared in Yahoo!, The Hollywood Reporter, and other publications. You can follow him at @jonccrow.

Quick fyi: Eric Ligman, a Microsoft Sales Excellence Manager, has gathered together a big list of free Microsoft ebooks and resource guides that will help you navigate through various Microsoft issues. Some of the texts are geared toward consumers; others toward IT professionals working with Microsoft products. A few handy titles include:

Most titles are made available as in epub, pdf, and mobi formats.

via Metafilter

Related Content:

Free Online Computer Science Courses

Free Textbooks: Computer Science

800 Free eBooks for iPad, Kindle & Other Devices

Image by Sound Opinions, via Flickr Commons

Roger Ebert seems to have resented star ratings, which he had to dish out atop each and every one of his hundreds upon hundreds of regular newspaper movie reviews. He also emphasized, every once in a while, his disdain for the “thumbs up” and “thumbs down” system that became his and Gene Siskel’s television trademark. And he could hardly ever abide that run-of-the-mill critic’s standby, the top-ten list. Filmgoers who never paid attention to Ebert’s career will likely, at this point, insist that the man never really liked anything, but those of us who read him for years, even decades, know the true depth and scope of his love for movies, a passion he even expressed, regularly, in list form. He did so for, as he put it, “the one single list of interest to me. Every 10 years, the ancient and venerable British film magazine, Sight & Sound, polls the world’s directors, movie critics, and assorted producers, cinematheque operators and festival directors, etc., to determine the Greatest Films of All Time.”

“Why do I value this poll more than others?” Ebert asks. “It has sentimental value. The first time I saw it in the magazine, I was much impressed by the names of the voters, and felt a thrill to think that I might someday be invited to join their numbers. I was teaching a film course in the University of Chicago’s Fine Arts Program, and taught classes of the top ten films in 1972, 1982 and 1992.” His dream came true, and when he wrote this reflection on sending in his list every decade, he did so a year nearly to the day before his death in 2013, making his entry in the 2012 Sight & Sound poll a kind of last top-ten testament:

Deciding that he must vote for “one new film” he hadn’t included on his 2002 list, Ebert narrowed it down to two candidates: The Tree of Life and Charlie Kaufman’s Synecdoche, New York. “Like the Herzog, the Kubrick and the Coppola, they are films of almost foolhardy ambition. Like many of the films on my list, they were directed by the artist who wrote them. Like several of them, they attempt no less than to tell the story of an entire life. [ … ] I could have chosen either film — I chose The Tree of Life because it’s more affirmative and hopeful. I realise that isn’t a defensible reason for choosing one film over the other, but it is my reason, and making this list is essentially impossible, anyway.” That didn’t stop his cinephilia from prevailing — not that much ever could.

Related Content:

Roger Ebert Talks Movingly About Losing and Re-Finding His Voice (TED 2011)

The Two Roger Eberts: Emphatic Critic on TV; Incisive Reviewer in Print

Roger Ebert Lists the 10 Essential Characteristics of Noir Films

4,000+ Free Movies Online: Great Classics, Indies, Noir, Westerns, Documentaries & MoreColin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture and writes essays on cities, language, Asia, and men’s style. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Quick note: Earlier this year, J. K. Rowling began writing new stories about the 2014 Quidditch World Cup Finals for Pottermore, the website for all things Harry Potter. Today, she followed up with a story that takes the form of an article published in The Daily Prophet: “Dumbledore’s Army Reunites at Quidditch World Cup Final” by Rita Skeeter. Here, Rowling gives us the first glimpse of the adult Harry Potter.

About to turn 34, there are a couple of threads of silver in the famous Auror’s black hair, but he continues to wear the distinctive round glasses that some might say are better suited to a style-deficient twelve-year-old. The famous lightning scar has company: Potter is sporting a nasty cut over his right cheekbone. Requests for information as to its provenance merely produced the usual response from the Ministry of Magic: ‘We do not comment on the top secret work of the Auror department, as we have told you no less than 514 times, Ms. Skeeter.’ So what are they hiding? Is the Chosen One embroiled in fresh mysteries that will one day explode upon us all, plunging us into a new age of terror and mayhem?

You can read the full story on Pottermore, where registration is required. Or the complete story can also be read on Today.com (without registration).

Related Content:

How J.K. Rowling Plotted Harry Potter with a Hand-Drawn Spreadsheet

Take Free Online Courses at Hogwarts: Charms, Potions, Defense Against the Dark Arts & More

The Quantum Physics of Harry Potter, Broken Down By a Physicist and a Magician

Harry Potter Prequel Now Online